| HERE BE CANNIBALS |

| RECENT CANNIBALISM IN NEW GUINEA |

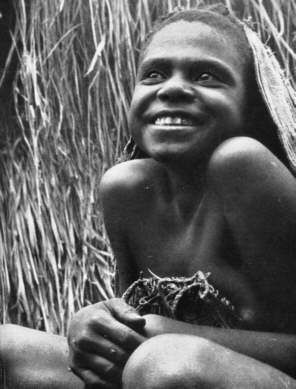

Whenever the men left the huts, either to go hunting or to go to the fields, they [the Kukukukus] always took their weapons with them. They were always ready either for defence or attack. They maintained a constant distrust of their neighbours; but towards us, who were complete strangers, their attitude was different. I gave them various presents in exchange for the specimens I gathered for the National Museum of Denmark; I joked with them, showed them photographs of other natives and let them listen to the tape recorder. They had an attractive, spontaneous sense of humour, and there was something very touching in the pleasure they evidently felt at meeting strangers who manifestly intended them no mischief. The children would come to clutch my arm if they wanted to show me something. The boys roared with laughter at my unskilful efforts to compete with them with bow and arrow.

It was difficult to imagine that these people were cannibals; but one day I was given a sudden revelation of their blood-lust. I had bought one of their tame pigs, and asked the headman of the village, a young warrior by the name of Momakowa, to kill it for me. He was normally a calm, peaceable fellow, not without a certain natural dignity; but when he set about killing the pig with his club, the joy of slaughter shone in his eyes and he battered the club again and again upon the head of the beast, although it had been killed by the first blow. He kept on till the blood spurted out; the children and women, who had gathered round him, screamed with delight. That incident enabled me to appreciate the reports of the reconnaissance patrols, and to believe what Jack had told me of the barbarous habits of the Kukukukus.

When a party of warriors takes an enemy prisoner, either in combat or by abduction, they tie the captive to a thin tree-trunk and bring him horizontally back to the village. So that the prisoner shall not escape, they then break his legs with a blow of the club, bind him to a tree, and adorn him with shells and feathers in preparation for the forthcoming orgy. Fresh vegetables are brought in from the fields and a big hole is dug in the ground for an oven. As a rule, the children are allowed to ‘play’ with the ‘prisoner’; that is to say, to use him as a target, and finally stone him to death. This process is designed to harden the children and teach them to kill with rapture. When the prisoner has been killed, his arms and legs are cut off with a bamboo knife. The meat is then cut up into small pieces, wrapped in bark, and cooked, together with the vegetables, in the oven in the ground. Men, women and children all take part in the ensuing orgy, usually to the accompaniment of dances and jubilant songs. Only enemies are eaten. If the victim is a young strong warrior, the muscular parts of his body are given to the village boys so that they can absorb the dead man’s power and valour. Although cannibalism has a certain magic significance, it derives mainly from a shortage of meat, a deficiency of proteins. Meat is a rare luxury for the Kukukukus, and I have often seen them, after burning grass off a hillside, devour with relish the charred corpses of rats, mice, lizards and other vermin.

Jack told me that, six months ago, two men had been eaten in a village, Jagentsaga, not far away; and that a month ago he had, by chance, found the hand of a man who had been eaten shortly beforehand. The rest of him had been hidden in the jungle. ‘They know,’ he said, ‘that we will punish them for cannibalism, so they do everything to conceal it now. But it still occurs and probably will do so for a long time.’

Jens Bjerre, The Last Cannibals, Michael Joseph, 1956.

New Guinea just wasn’t like Florida. ‘In the States when we wanted to relax,’ the Bozemans wrote friends, ‘we drove down town to the Dairy Queen for some ice cream. Now, we go down to Elisa and Ruth’s and watch a pig killing.

The Danis are great. We just love every one of them, even though they have pig fat and soot smeared on their bodies. We find it easy to put our arms around them and hug their smelly necks. This may sound funny to you but the Danis are very likable and they’ve already formed a big place in our hearts.

Within a few months Tom Bozeman had demonstrated that he was missionary material. He made remarkable progress in speaking the language, and his warm, easy manner won him the loyalty of the Danis living in the vicinity.

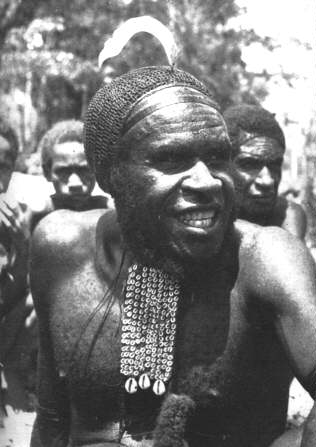

Probably Bozeman’s most significant achievement was gaining the friendship of Ukumhearik, the powerful chief. Ukumhearik showed more deference to Bozeman than to any of the other white men stationed in the valley. But Bozeman was also aware that the wily headman’s smiles did not change his deep-seated aversion to the gospel message.

Bozeman and Ed Maxey, who later would open a new mid-valley station at Tulim, worked together on a number of mission projects. They tramped over the stony trails, visited native villages, and slaved to learn the tricky native tongue. They also shared in an experience that no missionary had witnessed first-hand: the gruesome sight of natives consuming the body of a slain foe.

There were many reports of cannibalism but none of the missionaries had witnessed it. Danis had told Myron Bromley of victory celebrations after battles that ended in a feast on human flesh; he had even seen the smoke of the macabre victory fires.

Tom Bozeman tells the story:

The Danis around Hetigima told me that there was hardly a person in our area that had not tasted human flesh at one time or another. Yet, it’s funny when you talk to the Danis on our side of the Baliem. They say, ‘Oh, no, we don’t eat people; they do it on the other side of the river.’ But when you question the residents of the opposite side of the valley, they deny the charge and accuse the Danis in our area.

The Danis were always involved in battles and men were being wounded and killed so often, it had become a part of our lives. I remember the Sunday afternoon, though, when some of the villagers living near us dropped by our station after a big battle.

I asked them how the battle had gone. They replied, ‘Great! We killed a fellow, speared him right through the heart. He dropped dead and the enemy left him where he fell as they retreated. So we grabbed his body and hid it. Tomorrow we’re going to have a big feast. We want you to come and see it.’

None of us were really interested in seeing anyone eaten, but we thought we should verify the story. Next morning Ed and I went down to the Baliem River and crossed to the other side on a little Dani raft. People were already gathering on the other side of the river. There was the witch doctor and families – fathers, mothers, boys and girls. Before long hundreds of Danis had gathered for the feast. We walked with them for what must have been an hour’s hike to the side of a hill where the big event was to take place.

Already the dark-skinned natives, all painted up and dressed in their finest feathers and beads, were racing back and forth in a victory dance. They just run back and forth, the men in one group and the women in another. Sometimes they change the back-and-forth pattern and dance around in circles.

‘Well,’ I said to my Dani friends. ‘You’re going to have a cannibal feast, but where’s the body?’

Several little boys took me by the hand and led me over to the side of the hill.

‘Here he is,’ they cried, watching to see how the white man would react.

Sure enough, there was a man’s dead body under a layer of grass, where the corpse had been concealed since the previous day’s battle.

I could see the Danis were working themselves into a frenzy. They hardly had time for Ed and me to treat their battle wounds and to give them shots of penicillin.

It was ten o’clock in the morning and it was getting awfully hot. You can imagine the state of that corpse lying there in the hot sunshine.

The dance continued until everyone who was expected to be present had arrived.

‘Let’s go and cut a pole,’ one Dani yelled.

We were about a mile and a half from the edge of enemy territory in a no-man’s land where the battles are always fought. On the knoll of the hill above I could see that a crowd of the enemy had gathered to watch the proceedings. They had been told that their foes were going to eat the body of their kinsman. They were watching, fearfully waiting for the awful ceremony to begin.

A group of the victors came running with an eight-foot wooden pole and some dried banana fiber. Using the fiber as rope, the Danis tied the corpse to the pole. Then four strong young warriors hoisted the pole to their shoulders and carried the body, pierced with fifteen or more spear wounds, across the battle ground to a place closer to the mourners on the ridge of the hill. Crossing the fields, the carriers had to knock down fences as they struggled with their heavy burden. It was a nasty sight as they carried the bloody corpse for almost an hour’s walk to conduct the feast in full view of the enemy gallery.

Up on the hillside, black with people, the crowd was milling about, crying, weeping, and shouting.

‘Give us back our body,’ they cried. They wanted to have an honorable cremation for their dead warrior and they hated the shame of this terrible spectacle – the most stinging insult in Dani culture.

‘We’re going to eat him,’ the victorious crowd below shouted in derision.

Finally, the carriers dropped their burden on the ground and the banana fibers were untied. The Danis had brought the body as close as they dared, close enough for the defeated group to see, but not near enough to prompt a counterattack.

Ed and I pressed close. Then we saw scores of women, rushing en masse toward the body. Many of them were armed with digging sticks, the wooden poles that are used to break up the ground when they prepare their gardens.

As I was standing by the victim’s body, the women came in groups of about twenty to rotate in a circle about the corpse. In a torrent of worked-up rage, they began to jump up and down on the corpse, jabbing it with digging sticks, and stomping upon the man with their feet. Some of them were thinking, no doubt, about the battles in which their own loved ones had been killed. Now they were venting their wrath on the lifeless body underfoot: for an hour or more the women continued to dance and shriek their insults upon the slain foe.

While the pandemonium continued, some of the men had been building a fire near the body. As the women stopped their yelling and frenzied actions, I saw a man advancing with a knife.

It was a knife they had made from one of our long spikes. It had been pounded until it was flat and then it was sharpened to a keen edge. The men started to remove a toe from the corpse. But the knife was not the proper tool, so he went for his ax. I was standing by taking pictures.

Now another Dani came up with some bamboo knives. These knives, by the way, are as sharp as any steel blade known to civilized man. The man with the bamboo knife began to cut the meat from the dead man’s calves. I became nauseated. I saw Ed Maxey, his face green, run to the edge of the crowd.

The two missionaries, sickened and depressed by the awful rite of Cannibal Valley, returned to their homes. They wanted to blot from their minds the ugly things they had witnessed.

Russell T. Hitt, Cannibal Valley, Hodder and Stoughton, 1963.