|

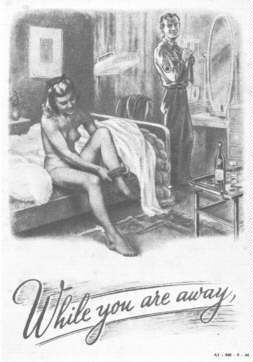

Love, Sex and WarJohn CostelloFrom Chapter 14: The Girls They Met ‘Over There’

|

Picadilly tarts and titled ladies

PROSTITUTION AND ARMAMENTS MANUFACTURE share the dubious distinction of being the principal commercial beneficiaries of twentieth-century warfare. In common with the ‘merchants of death,’ the women who pursued ‘the lively commerce’ discovered that fear generated by war was a potent stimulant to their business. Long lines of soldiers formed outside the French military brothels which catered for the sexual needs of the Allied armies who fought on the Western Front in World War II: according to the dictates of good discipline, officers’ whore-houses were indicated by blue lights and other ranks’ by red lamps. For those who preferred to risk contracting venereal infection rather than copulate under military supervision, there was always a willing ‘mademoiselle’ to be found in staging towns like Armentières, where thousands plied the ancient trade that made one of them the subject of the popular war song.

These female ‘camp-followers’ had always been part of the baggage-train of European armies. In the 1620s, during the Thirty Years’ War, it was recorded that one forty thousand-strong army which devastated the Rhineland was accompanied by ‘a hundred thousand soldiers’ wives, whores, servants, maids, and other camp followers.’ The practice spread to the United States during the Civil War, when the regiments of women who followed General Joseph Hooker’s Army of the Potomac became known as ‘Hooker’s girls,’ coining the popular colloquialism for prostitutes.

Nell Kimball, the celebrated New Orleans ‘Madam,’ ascribed the increased trade that World War I brought her famous whorehouse to the epidemic of anxiety that gripped the male population after the United States became a belligerent in the spring of 1917:

Every man and boy wanted to have one last fling before the real war got him. One shot at it in a real house before he went off and maybe was killed. I’ve noticed it before, the way the idea of war and dying makes a man raunchy, and wanting to have it as much as he could. It wasn’t really pleasure at times, but a kind of nervous breakdown that could only be treated with a girl and a set-to.

The same ‘nervous breakdown’ in European soldiers brought the ‘red-light regiments’ out into the streets of Berlin, Paris, and London – leading to the 1917 music hall quip that the American doughboys were ‘Over here to make the underworld safe for democracy.’ The London whores were considered so numerous by the New Zealand Red Cross that they dispensed six prophylactic kits each to protect the health – if not the morals – of their native sons, whose six shillings-a-day pay made them targets for streetwalkers used to British soldiers who had only their daily sixpence to offer for their pleasure.

Nor was it just the Piccadilly tarts whose avarice was stirred by foreign military uniforms in World War I. A Canadian major was invited by a titled lady to spend the weekend at her country estate. ‘You men in the army lead such dangerous lives, and may never return from the next offensive,’ announced his hostess over dinner, explaining that her husband had recently been killed in action. ‘It is our duty to make your leave enjoyable, so here I am.’ It was impossible for the major to resist such an invitation, but he was to be nonplussed when the butler confidentially advised him the next morning, ‘Her ladyship has the greatest difficulty maintaining this estate. It would be helpful if you would leave a contribution of a hundred pounds.’ (pp. 287-288)

Sexual logistics

Prostitutes were made synonymous with venereal disease not just by the Germans, but also by the British and United States army commands, who declared war on the women who had been blamed for the million and a half syphilis and gonorrhoea casualties suffered by the Allied armies in World War I. The Wehrmacht applied the lessons learned twenty years earlier when the Kaiser’s army strictly regulated the ‘sexual logistics’ of the troops and thereby cut its VD casualty rate to half that of the French army by 1918. Corpsmen collected the fees at the medically supervised military brothels behind the front lines, imposing a strict ten-minute time-limit per man during the evening ‘rush hour’ and providing prophylactic treatments as well as keeping a detailed log of the visitor’s rank and regiment so that fines could be levied from those who failed to report contracted venereal infections.

In World War I the venereal infection rates of the British army were seven times higher than the Germans, principally because national prudery prevented the British high command from acknowledging that there was any problem at all until 1915, when the Canadian and New Zealand prime ministers forced the chiefs of staff to issue free contraceptives to the troops. (p. 289)

Freelance prostitution

Blitzing the brothels might have been successful in checking a possible wartime explosion of organized vice in the United States, but it simultaneously created a new phenomenon, according to Dr John H. Stokes of Philadelphia, who wrote in the American Medical Journal, ‘The old-time prostitute in a house or formal prostitute on the street is sinking into second place. The new type is the young girl in her late teens and early twenties... who is determined to have one fling or better... The carrier and disseminator of venereal disease today is just one of us, so to speak.’ The burgeoning of freelance prostitution in the United States was soon providing spicy copy for the press, as lurid reports flooded in from major navy bases and army camps. Cab drivers serving the US Navy’s large base on the Virginia Coast were reported to have been threatened with losing their licences for graft they received by ferrying customers to and from illicit whorehouses. Even the staidly moral Time Magazine ran a piece on the social problems of the US Navy’s principal east-coast port:

Whereas before Pearl Harbor, the majority of Norfolk’s prostitutes were professionals, today probably eighty-five to ninety per cent are amateurs. Many are young girls lured to Norfolk by the promises of big paying jobs. Hundreds of these girls arrive every week. They hang around bus terminals while phoning for a room somewhere... Farm girls and clerks from small towns find it easy to have all the men they want... many do not charge for their services.

In San Antonio, Texas, one out of every four ‘car-hops’ – as the streetwalkers were called – was reportedly infected with VD, causing the ‘professional prostitutes’ to blame the amateurs: ‘they say the young chippies who work for a beer and a sandwich are cramping their style.’ In New York State, Canadian girls often crossed the border on evening trips into Plattsburg and tended to leave their infection behind; the local community pleaded for action to seal off the frontier to them. (pp. 290-291)

One night in Miami

The much-publicized official crackdown on organized prostitution encouraged servicemen to take advantage of the teenage ‘Victory girls’ who swarmed round military installations chasing men in uniform. By 1943, the army and navy were so concerned about complaints that girls and women were roaming the streets of Miami that a special directive was issued to military police to stop men soliciting these ‘women of easy virtue.’ But they were soon reporting failure to curb ‘soliciting of women in the streets’ because ‘the females in question often take the initiative in making the acquaintance of a soldier or sailor.’ Off-duty servicemen flocked into Miami every night from the large number of navy and army bases at the outskirts of the resort, so the women’s search, according to the report, was ‘usually crowned with success because of the large number (about fifty thousand) of young and virile soldiers and sailors stationed or visiting that area, a larger number of whom, likewise, appear to be primarily interested when off-duty in seeking the companionship of the opposite sex.’

Colonel Eugene L. Miller and Navy Captain Thomas E. van Metre surveyed the extent of the problem on a Thursday, an average night free of the wider excesses of Saturday. Cruising around in an unmarked car they visited the bars, dance-halls, and parks and found many ‘well dressed, unattached women sitting at bars and tables in saloons and nightclubs’ whose obvious intent was ‘picking up a soldier or sailor, which they usually succeeded in doing before the saloon or nightclub was closed at midnight.’ At the Tatem Hotel, Miami Beach, they stopped at the popular 634 Club and Charlie’s, whose burlesque and striptease shows chaplains had accused of immoral excess. Members of the audience were quizzed, ‘but no grown person interviewed considered them to be lewd or obscene.’

The Servicemens’ Recreation Centre at Pier 42 had closed early, but the Colonel and Captain noted, tactfully, that it was ‘well managed but not well patronized.’ The Frolic, Bali Night Club, Club 600, Bowery, and The Spur Bar were packed, and in most of the bars it was very noticeable that the female population considerably exceeded the male – and that girls went to the powder room for an excuse to come back and sit with newcomers. At the Bali, the ‘petting’ that was going on at the tables included many uniformed WAVES, ‘one of whom was observed to be “petting” with an Ensign.’ The United States uniform was being treated even more disrespectfully at the ‘rough and tumble’ Spur Bar, which was packed with a crowd of semi-intoxicated sailors – one drunken CPO had already passed out on a bench.

In the early hours of the morning the investigators found that the prophylactic station near the Navy Sub-Chaser school was crowded with sailors who had presumably already found sexual satisfaction. Signs of promiscuous behaviour were evident at every corner: ‘many enlisted personnel and their girls, when not in sight of the shore patrol, were observed locked in each other’s arms, petting and kissing as they moved down the streets. As they progressed farther from the middle of the town, these couples were observed disappearing into the alleyways, yards, parks, and shrubbery.’ Petting went on openly in ‘practically all the cars, even though the lights around were bright enough to make the performance easily visible from almost every direction.’ But although the survey concluded ‘no actual immoral acts were observed,’ the inescapable impression was ‘one of great immorality with no effective means being taken to prevent it. Even in instances where there were no immoral intentions, the fact that the men were up and out in the streets until all hours of the morning would appear to leave them ill-fitted for a strenuous training programme the following day.’ (pp. 291-293)

Submarine wolf-packs

Brothel girls in the French ports of Lenient, Brest, and La Pallice, from where the submarine wolf-packs sailed to ravage the Atlantic convoys, were also suspected of spying for the Allies and passing on the names of U-boats about to put to sea. Some commanders quarantined their crews for three weeks before a patrol to protect their health and prevent the disclosure of their missions, since their men always went on spree before sailing. To avoid the disease and security hazard posed by the seaport brothels, the Todt Organization built ‘rest-camps’ as well as the mighty concrete pens for the U-boats. Equipped with beer and dance halls, the camps were staffed with plenty of imported German females, who with the German Red Cross nurses could be persuaded to share the comfortable hotel-like accommodation provided for the crewmen.

The occupation of France made the Wehrmacht aware of the degree to which soldiers and sailors away from the homeland developed a passion for the pursuit of the native female population. This was a phenomenon long familiar to British military commanders from policing an overseas empire that reached across the globe. The wartime report of an English army physician had observed that there was a ‘well-known relationship between the distance from home and VD incidence,’ with length of individual service abroad the chief factor.

Among other ranks, with their more limited resources for sublimation through social and intellectual interests, the effect of long continued service overseas is seen in the increase in the venereal disease rate and, perhaps, in the type of commerce from which infection results. The sense of guilt lessens and the proportion of cases of the more sordid form of prostitution seems to increase. (pp. 297-298)

The Cairene tarts

For sheer variety of sexual diversions, few red-light districts in the world could match Cairo during World War II. The ‘pleasures’ offered by the celebrated Cairene tarts reached something of a peak of sexual exoticism in the frenzied year before the Battle of El Alamein when British and Australian troops poured in on their way to halt Rommel’s advance across the western desert. ‘GIVE US THE TOOLS AND WE WILL FINISH THE JOB’ was the cheeky sign one Cairo brothel-keeper hung out after Churchill’s famous 1942 appeal to the United States. In the back alleys of the ancient city of the pyramids there was no shortage of servicemen – or whores – who obliged. The incidence of murders and rapes, however, prompted the British military police to embark upon one of their periodic efforts to put the worst districts of the city out of bounds. But policing the squalid streets, even in the name of King Farouk, proved impractical. The legend of wild sexual practices, including squalid whore-houses which offered the spectacle of women copulating with a variety of animals – among them a donkey, according to a former member of the Black Watch Regiment – continued to lure the hard-bitten soldier and curious journalist. A British war correspondent, however, recalled that not all the sights in the notorious Wagh EI Birkhet were so depraved: ‘the only significant thing in a boring, rather nauseating hour – a fellah bowing in prayer to Mecca on the roof of a brothel, through the lit winnows of which we could see Baudelaire’s “affreuse juive.”’

While Rommel’s Afrika Korps was still advancing on Cairo, one prudent Cairo madam evacuated her girls to what she hoped would be the safety of Alexandria. She was doomed to disappointment: a lost Italian pilot dropped a single bomb and demolished her house of ill-repute. The incident also faced the British Army authorities with a dilemma after Cairo GHQ was told that the corpses of six British officers had been dug out of the rubble. It was decided to spare their next-of-kin painful embarrassment by camouflaging the true circumstances of their deaths. Accordingly the three officers who had been upstairs ‘on the job’ were posted as ‘killed in action,’ and the three waiting downstairs for their turn were listed as ‘killed on active duty.’

Italian as well as British troops appear to have found that desert fighting heightened the sexual urge. Mussolini, who was a self-proclaimed sexual adventurer, saw to it that his army in Cyrenaica was provided with mobile brothels for the forward troops and whorehouses in the rear areas. After Tobruk’s surrender in 1941, the garrison brothel presented a British colonel with a difficult dilemma when, according to the war correspondent who acted as translator, the sous maîtresse offered to put her girls ‘at the disposition of the British army’:

Thousands of prisoners had been rounded up. Now ten more were taken – the ten tarts of Tobruk. They stood in line in front of the whitewashed, two-storied building which was both their home and red-light house. A woman of fifty, grey-haired, hard-faced, tawdry in attire, played the role of a very nervous CO to the girls. A motley assortment, none of them was physically attractive. Their faces were hastily daubed with paint and powder, and the best one could say of them was that they looked the part – blowsy, all of them. One, an ersatz blonde, might have been in her early twenties; a couple of others, brunettes, would have been passable had they been properly turned out. As for the others: they were human nonentities – and very frightened.

I translated. The colonel frisked his moustache with the back of his hand.

‘Tell them,’ he said in anger, ‘tell them to take ten paces to the rear – immediately!’

‘And tell them this,’ added the colonel, ‘tell them they stink!’

This I managed to break down, in translation, to a milder term which conveyed to the undermistress and the girls that their offer had been rejected. Before I left we found their books, or score sheets. They had all been very industrious. One girl named Antoinette had a pretty regular batting average of fifty per diem, which had been topped by only a few of the others on very rare occasions. Antoinette, the undermistress told me, was the young blonde. (pp. 300-302)

The Italian princess

The Italian campaign more than any other in World War II confronted the British and American military commanders with their impotence when it came to coping with endemic prostitution. A foretaste of the problem was given by British medical officers in Sicily, who were treating forty thousand VD cases a month, twenty times more than the number treated in England. As one report advised, ‘prostitution is almost universal among all but the highest class of Sicilian women.’ Government-regulated brothels also existed in all of the large towns. Control had broken down, although General Patton wasted no time trying to restore it by putting US Army medical teams into Palermo’s six large houses of prostitution. This did not endear him to General Montgomery, his arch rival, whose pride as well as his puritanism was offended when it was announced that the brothels were open for business again – under US Army management.

The invasion of Italy proper magnified the scale of the problem. But it was the capture of Naples in October 1943 that pitched the American and British commands into a two-year battle with an army of prostitutes – a battle Allied chaplains and doctors of both armies would later concede they lost.

Naples became the main staging port for the gruelling Italian campaign as well as the principal rest and recreation centre for thousands of Allied troops. Wine and girls were as plentiful as food was scarce for its inhabitants, who were packed into what one British officer called ‘human rookeries.’ K-rations became the passport to the passion GIs discovered Latin women could bring to the most transient of casual sexual encounters. ‘Even when they aren’t in love the Italians ape the mannerisms of the lover. Thus they can be joyous at eighty. Italian love is both articulate and silent. The lovers quickly knock down any barrier between them.’

In Naples, as one official American report put it, ‘Women of all classes turned to prostitution as a means of support for themselves and their families.’ A British officer recorded his surprise that Prince A. and his twenty-four-year-old sister came down from their palace to his office. ‘The purpose of the visit was to inquire if we could arrange for his sister to enter an army brothel. We explained that there was no such institution in the British Army. “A pity,” the Prince said. Both of them spoke excellent English, learned from an English governess. “Ah well, Luisa, I suppose if it can’t be helped, it can’t be.” They thanked us with polite calm, and departed.’

All a Nazi plot

There was an estimated female population in Naples of over a hundred and fifty thousand, many of whom became freelance whores, compounding the problems caused by the estimated fifty thousand regular prostitutes in the ‘undetermined number of brothels which had previously been regulated by the civilian government and used by the German and Italian Armies.’ A month after Naples had been liberated, the US 5th Army headquarters quarantined a large bordello outside the city and placed the other brothels off-limits to American troops. But the strategy that had failed in North Africa was even less able to withstand the assault of the regiments of hungry Italian women. Prostitutes refused to work in army brothels for 20-50 lira (50 cents or 2s 6d) per man when they could command fantastic prices of $10, $15, or even $20 (£5) outside. Uncontrolled prostitution sent VD rates rocketing to over a hundred per thousand men by the end of the year, and almost every infected GI gave Naples as the source of infection.

The British Army, which had no clear strategy other than the ineffective one of placing sections of Naples out of bounds, reacted to the soaring VD rate by blaming it on the Germans. A circular that arrived in all units by Christmas warned:

From reports that have been received it is apparent that prostitution in occupied Italy, and Naples in particular, has reached a pitch greater than has ever been witnessed in Italy before. So much is this so that it has led to a suggestion that the encouragement of prostitution is part of a formulated plan arranged by the pro-Axis elements, primarily to spread venereal disease among Allied troops.

British military intelligence might have believed in a sinister Nazi plot, but a US Army doctor discerned that the dramatic rise in venereal disease was not a product of the German’s corruption of Italian womanhood. ‘It was not lust, but necessity, not depravity of the soul but the urge of the instinct to survive which led numerous women into the ranks of the amateur prostitute on whom regulatory legislation had little or no effect.’

The magnitude of the sexual problems that confronted the Allies in Italy was put into sharp focus when US Army medical officers conceded victory in the battle against venereal disease in Naples to the prostitutes: ‘Women of all classes turned to prostitution as a means of support for themselves and their families. Small boys, little girls, and old men solicited on every street for their sisters, mother and daughters and escorted prospective customers to their homes.’ When the casualties of sexual infection exceeded those from the battle front, special ‘Casanova Camp’ treatment centres were set up, surrounded by barbed wire to keep the men in – and the Italian women out.

The indignity of being processed through one of these American VD treatment centres was vividly described by army veteran John H. Burns. The infected GI, he reported, had to put on special fatigues:

On the back of the jacket and on the trouser leg were painted these large and smelly letters: V D.... Finally it came his turn at the end of the file to enter the dispensary. Inside the screen door the line forked into two prongs and was being funnelled past two GIs, each with a hypodermic in his hand. Along the walls of the room were electric iceboxes. And many little glass ampoules of an amber liquid. Ahead of him were men with either arm bared or with their buttocks offered like steak to the needle. ‘They give ya a choice on where ya want ya shot,’ the blond boy said. ‘If ya take it in the ass, they’ll use a longer needle ta get through the fat. My advice is ta take ya shots round the clock. Then none of ya four parts gets too sore. Ya’ll be hurtin anyhow.’ Then... he felt already the stinging in his other shoulder. All his life telescoped down to three-hour periods and a hypodermic needle and yellow drops dribbling out of it. What was it called. Pncilin? Penissiclin? Pencillin? (pp. 303-6)

Paternity support?

The number of tents that made up the ‘Casanova Camps’ that were established near the Fifth Army Rest Centre outside Naples were visible evidence of the victories scored by the city’s prostitutes. So too were the thousands of pathetic mothers who crowded British and American military headquarters trying to claim paternity support. One British officer recorded how one woman came in and admitted having two lovers, one a GI and the other a Tommy. Who was going to pay her damages? The Cockney sergeant sitting next to the translator said solemnly, ‘Tell her to wait until the child is born. If he says, “Thank you Mummy” when she feeds him, then he is British, but if he says “Thanks a lot Mom,” he’s American.’ (p. 307)

John Costello, Love Sex and War: Changing Values, 1939-45. William Collins, London, 1985.