|

Love, Sex and WarJohn CostelloFrom Chapter 16: Yielding to the Conquerors

|

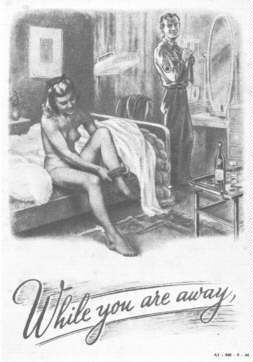

It seems to me that while the American Forces are doing their big part in the invasion of Europe in a temporal way, we are also invading other lands in a moral and spiritual way, and the imprint we are leaving on the invaded peoples is not too good a picture. US Army Chaplain, June 1944 (p. 333)

Liberating whoredom

‘YOU WILL GO THERE AS LIBERATING HEROES and those women will be eager and urgent in the solicitation of you. Now bear these facts in mind,’ American troops embarking for the D-Day invasion were warned. ‘The women who will be soliciting your attentions are prostitutes of the most promiscuous type.’ Mindful of the degree to which the strength of the Allied armies in Italy had been sapped by VD spread by prostitutes, and fearful that medical services in France had been run down by the German occupation, Allied medical and military planners had taken unprecedented measures to keep the troops spearheading the liberation of Europe from becoming casualties of sexual disease.

A fleet of mobile VD treatment centres staffed by two medical officers and six orderlies had been mounted on three-ton trucks ‘to treat as far forward as possible all cases of primary and recurrent venereal diseases.’ Equipped with thousands of high-strength penicillin doses, they were to provide quick treatment injections to keep up strength at the fighting front. The hitherto limited supplies of the ‘wonder-drug’ that was to prove a potent weapon in the Allies’ arsenal during the ‘Crusade for Europe’ had already saved thousands of battle casualties from serious infection. Some medical experts were against using the ‘magic bullet’ of penicillin as a fast cure for venereal disease on the grounds that it would remove a powerful incentive to restraint by the troops. But strategic rather than moral considerations enabled the D-Day planners to overcome such objections.

The easy availability of a quick cure for the wages of sin was reassuring for those members of the Allied forces who were encouraged by the enthusiastic reception they received from the women of the towns and villages of Normandy to join an intimate celebration of the liberation. Nor did their commanders interfere. Within hours of the American capture of Cherbourg, two houses of prostitution were doing a roaring trade ‘run for, and indirectly by, American troops, with the familiar pattern of the designation of one brothel for negro troops and the other for white, with a military patrol stationed at the doors to keep order in the queues which formed.’ (pp.335-336)

French welcome societies

American officers were not moral exemplars. Their activities brought charges from the French town council in Bayeux that they had made ‘a public pastime’ of whoring, according to another army chaplain:

German officers had run their brothels quietly. They did not demand that the owners of private billets couchez avec as American officers did. The French Welcome Societies stopped furnishing girls to American Army camps for dances because of immoral treatment. I personally saw about a dozen officers taking French girls into their billets during the dance, turning off the lights and being there from one half to one hour at a time. (p. 337)

Traiteur collaborateur

Not every sexual encounter was with a prostitute, as one Scottish sergeant fondly recalled of his night of passion with a young girl called Janine just after Brussels were liberated:

A warmth and pleasurable joy swept over me as I lay in the arms of the loveliest girl in the world, her long hair falling like silken water over my shoulders. Her lips filled me with gasping urgency and my stroking hands reached for some joy I never knew existed. The girl Janine, in my arms, whispered to me, stroking my head, kissing my face and reaching for the happiness that eludes men and women in time of war, never knowing if this day is going to be your last on this earth. Her insistent hushing as we made love lulled me into another sleep, till in a rushing dream I was roused by her strident tones, ‘Allez Jock... Six heures... Allez!’ All that day I was filled with one aim, to get off duty as quickly as possible and return to the Avenue du Canada. My heart was thumping like a child at his first party as I jumped from the tram at the terminus, my small pack bumping heavily on me with its load of cigarettes and chocolate... then I saw the house... Janine’s house... Its walls were now daubed with obscenities and rough painted swastikas. Above the door were two large scrawls, ‘Traiteur Collaborateur.’ There was no movement within the silent rooms, only the whispering of a torn curtain in the window of her bedroom. A tear fell from my eye as I thought of Janine – then I walked into the war once more.

In Brussels, it became impossible for a British soldier to walk ‘more than ten to twenty yards’ without being accosted by a fresh streetwalker. By March 1945, the VD rate had climbed to such an alarming level that SHAEF headquarters shipped penicillin supplies to civilian hospitals in the Belgian cities to treat the prostitutes who were suspected of harbouring sexual infections. With the push across the frontiers of the Third Reich now gathering pace, it had become essential to cut down the VD rate and maintain the strength of front-line units. When German cities and towns began falling to the Allied advance, SHAEF headquarters counted on Eisenhower’s ‘non-fraternization’ policy to check the epidemic of promiscuity which afflicted the ‘Crusaders for Democracy.’

The chaos into which the Thousand Year Reich crumbled during the final months of World War II combined with the sexual and physical hunger of a large number of German women defeated any strict enforcement of non-fraternization. (pp. 339-340)

Four cigarettes good pay for all night

When Germany surrendered on 7 May 1945, an estimated four million fathers and elder brothers of the defeated male population remained in Russian captivity. This only increased the pressures on a sexually starved female population to yield to their conquerors in an ‘unofficial polygamy’ with the men of the occupying armies that was to send the post-war bastard population soaring – in 1945, one out of every five German births was estimated to be illegitimate!

That a large percentage of these children were fathered by Allied soldiers was an indication of the rapidity with which General Eisenhower’s original ‘non-fraternization’ policy had broken down. The erosion had begun when Hitler’s vaunted Westwal defence cracked in March 1945 and the ‘liberation’ of German women began – despite a US Army decree that contracting VD inside the German frontier would be taken as prima facie evidence of fraternization, entailing a $65 fine. Neither the policy nor the stiff penalty were effective. Officers and soldiers in every Allied army were soon fraternizing openly. As an American intelligence officer reported from Aachen, one of the first towns in the Third Reich to fall under Allied control, it was difficult for the average GI to regard the native women as hostile:

The essential kindness of the American soldier was in evidence. Soldiers helped German housewives with their chores, played with the children and through other small acts of friendship made living more tolerable through the creation of a friendly atmosphere. Conversation with some of those soldiers evoked such comments as, ‘These Germans aren’t bad people. We get along with them OK. All you’ve got to do is to treat them good and you have no trouble.’

Germany’s female population did not resist the demands of the occupying soldiers. As one American report put it, ‘Women were told that it was right and patriotic to bear children for any soldiers desiring the same.’ They soon discovered that sex could be traded for food and cigarettes from the GIs, who found it easy to forgive the Germans, unlike their British comrades who had suffered the bombing of their homes by the Luftwaffe. The average GI could also identify with the cleanliness and domestic values espoused by the conquered but still house-proud womenfolk. ‘Despite living in cellars and bombed buildings, the German civilians had kept clean,’ one US Army intelligence officer noted. ‘The girls, in particular, look out of place amid the debris. They wear bobby-sox and pigtails with gay coloured ribbons. They wear thin dresses, and they are fond of standing in the sun.’

Soaring VD rates were disturbing proof that ‘getting-together’ increased in the first weeks of peace. Now there was no longer any fighting, the sexual hunger of Allied troops feasted on that of German women separated from their husbands, many of whom had risked imprisonment in concentration camps to solicit the favours of Polish and Russian slave workers. Negro regiments were especially susceptible to fraternization. There were many white women who were eager to exorcise Hitler’s racial myths in the most intimate manner.

‘We cannot expect the GI to behave differently,’ observed an American officer who urged the abandonment of the unworkable ‘non-fraternization’ policy,’ ‘After all he is human. He wants companionship – he’s lonely, and the Germans are pastmasters at getting around men who feel that way.’ Physical and sexual hunger combined with a flourishing black market to make sex a commodity to be traded for the necessities of life. ‘In this economic set-up, sex relations, which function like any other commodity, assume a very low value,’ explained one US Army survey. ‘Because of this situation, plus the fact that every American soldier is a relative millionaire by virtue of his access to PX rations, the average young man in the occupation army is afforded an unparalleled opportunity for sexual exposure.’ In Berlin immediately after the end of the war, German girls considered ‘four cigarettes good pay for all night. A can of corned beef means true love.’ (pp. 343-345)

Upheaval

American war correspondent Julian Bach reported on what he called a ‘vast social, ideological, and moral upheaval’ that was taking place in the ruins of the Thousand Year Reich:

When a pack of king-size cigarettes brings $18.50 on the Berlin black market, then the economy is sick. When a buxom fraulein, taught by Hitler to loathe and despise all ‘North American Apes,’ turns around and, for the sake of a handful of Hersheys, cuddles up to a GI whose name she does not know (and probably could not conveniently pronounce), then moral values are in travail.

So much fraternization was taking place in Germany during the spring and summer of 1945 that GIs jokingly compared it to prohibition. One staff sergeant in the 30th Infantry Division explained the difference between non-fraternization and prohibition: ‘In the old days a guy could hide a bottle inside his coat for days at a time, but it is hard to keep a German girl quiet in there for more than a couple of hours.’ A tank driver commented, ‘Fraternization? Yeh, I suppose it’s all right. Anyway I’ve been doing it right along. But every now and then I wake up in a cold sweat. I dream that we are at war again and the German bastards I’m fighting this time are my own!’ (p. 345)

Objectors are ‘die-hard Nazis.’ Japan more accomodating

In Heidelberg and other cities ex-Wehrmacht servicemen did not share this sentiment. Die-hard Nazi groups began a surreptitious campaign against fraternization, threatening vengeance with posters that proclaimed:

What German women and girls do

Makes a man weep, not laugh

One bar of chocolate or one piece of gum

Gives her the name German whore.

A very different attitude was encountered in Japan where, to the embarrassment of General MacArthur and the delight of the GIs, more than adequate provision had been made for occupying soldiers. In accordance with the oriental view of sex as a necessity, uncomplicated by the taboos and inhibitions of Christian doctrine, the nation that had dispatched medically inspected whores to army bordellos on the Pacific outposts of its empire also set up ‘rest and recreation’ centres for the American army. To forestall a wholesale violation of Japanese women, plans had been made even before the first American soldier had set foot in Tokyo to build a six million dollar bar and cafe complex to house five thousand women who, according to the coy announcement in the Nippon Times, ‘will entertain Allied troops.’

When the first GIs arrived, they found temporary ‘Special Recreation Centres’ had already been set up in the surviving unbombed factories – only nine of the three hundred and ten brothels that had packed Tokyo’s celebrated Yoshiwara red-light district had survived the American firestorm raids. Price-lists for these ‘establishments’ were posted on the quartermaster bulletin boards in all US Army camps – with the ever-present reminder about the need for prophylaxis to avoid infection:

20 Yen – a buck and a quarter – for the first hour, 10 yen for each additional hour and all night for 50 yen. If you pay more, you spoil it for all the rest. The MPs will be stationed at the doors to enforce these prices. Trucks will leave here each hour, on the hour. NO MATTER HOW GOOD IT FEELS WITHOUT ONE, BE SURE TO WEAR ONE.

In addition to the ‘Special Recreation Centres,’ the street corners of the bombed-out Yoshiwara district were soon crowded with young Japanese girls sporting gaudy rayon pyjamas and crude attempts at Western make-up and hairstyles. (pp. 346-347)

113 prostitutes on duty

A veritable typhoon broke in the American press after a navy chaplain had complained to Newsweek magazine that the liberty men on his ship were directed to ‘houses of prostitution’ in the Yokosuka area where there were separate ‘geisha houses’ for officers and chiefs. He had personally watched ‘a line of enlisted men, four abreast, almost a block long, waiting their turn,’ and his letter continued:

MPs kept the lines orderly. As the men were admitted into the lobby, they would select a prostitute (113 on duty that day), pay 10 yen to the Jap operator, then go with the girl to her room. When the men returned they were registered and administered prophylaxis by Navy corpsmen. (pp. 347-348)

We lost our civilization in winning the war

The willingness of the female population of a defeated enemy to give themselves to the occupying troops demonstrated the ascendancy of human nature over military policy. But the tacit approval of relationships that it signalled did not please the keepers of America’s moral conscience, as a service chaplain spelled out:

We have won the victory of arms. We believed that the civilization for which we fought was immensely superior to the Kultur of the German, who under Hitler’s leadership placed boys’ and girls’ camps near together with obvious expectation. We have read with horror the Japanese concept of women as men’s playthings. But will the parents and families to whom American servicemen return, their thinking warped by ‘take-a-pro’ morality, will these families be convinced that the better civilization has won? Or that we lost our civilization in winning the war?

While the majority of soldiers’ affairs were as transient as their military service, for some of the men in the US armed forces the romances and affairs with the girls they met overseas became permanent. Many GIs were first generation Americans, the children of European immigrants, and marriage to an Italian, French, or even German girl was a romantic adventure that renewed links with the ancestral homeland. The excitement of wartime had prompted Americans stationed in Britain to take as their brides over sixty thousand English girls. Many had left their new wives pregnant, others had left their girlfriends unwed and ‘in the family way’ with promises of returning for the marriage that would bring a passport to America. (p. 348)

The promised land. Operation War Bride

Many other European women who thought they were going to marry a Yank would never see the promised land. ‘There were, I remember, American GIs and officers who most cruelly betrayed and seduced Neapolitan girls, concealing from them and their families that back in the United States they’d a wife and kids,’ wrote Sergeant James H. Burns.

Such was the appeal of America as the land of ‘many’ British girl’s wartime dreams that ‘some’ of them married on trust. By early 1946, the US immigration department was snowed under dealing with permits for eight thousand French, Italian, and Dutch war brides in addition to the four thousand residency applications submitted by Australia and New Zealand women and over sixty thousand from Britain. A transit camp had to be set up in the south of England to process the British migration, which the War Department called ‘Operation War Bride,’ and early in 1946 the first six hundred sailed for the United States aboard the steamship Argentina, which had been specially fitted out as a nursery ship. It was the start of what was to be the largest single influx of mothers and children into the United States in two centuries. (p. 349)

Trouble at home

Three out of every four American servicemen had sexual encounters overseas that were to influence the national image of romantic womanhood back home. ‘My husband says the girls in Europe aren’t like us. They’re more human and understanding,’ became a common complaint of the American wives of veterans in the year after the war ended. (p. 351)

John Costello, Love Sex and War: Changing Values, 1939-45. William Collins, London, 1985.