|

Marx, Engels, Lenin?

An attempt to stick to real names fails due to unreliable, conflicting sources |

|

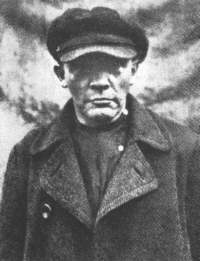

| Nobleman Ulyanov wearing his wig | A few seconds later, looking like a tramp |

Karl Marx – or Moses Levy Mordecai, or Mordecai Levi, it is unclear what his real name was – could not have been unaware of the weaknesses, indeed dishonesties, of Engels’ book The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, published in German in 1845, since many of them were exposed in detail as early as 1848 by the German economist Bruno Hildebrand, in a publication with which Marx was familiar. Moreover Marx himself compounds Engels’ misrepresentations knowingly by omitting to tell the reader of the enormous improvements brought about by enforcement of the Factory Acts and other remedial legislation since the book was published and which affected precisely the type of conditions he had highlighted.

In any case, Marx brought to the use of primary and secondary written sources the same spirit of gross carelessness, tendentious distortion and downright dishonesty which marked Engels’ work. Indeed they were often collaborators in deception, though Marx was the more audacious forger. In one particularly flagrant case he over-reached himself. This was the ‘Inaugural Address’ to the International Working Men’s Association, founded in September 1864.

Presumably with the object of stirring the English working class from its apathy, and anxious therefore to prove that living standards were falling, he deliberately falsified a sentence from W. E. Gladstone’s Budget speech of 1863. What Gladstone said, commenting on the increase in national wealth, was:

‘I should look almost with apprehension and with pain upon this intoxicating augmentation of wealth and power if it were my belief that it was confined to the class who are in easy circumstances.’

But, he added,

‘the average condition of the British labourer, we have the happiness to know, has improved during the last twenty years in a degree which we know to be extraordinary, and which we may almost pronounce to be unexampled in the history of any country and of any age.’

Marx, in his ‘Inaugural Address’ has Gladstone say:

‘This intoxicating augmentation of wealth and power is entirely confined to classes of property.’

Since what Gladstone actually said was true, and confirmed by a mass of statistical evidence, and since in any case he was known to be obsessed with the need to ensure that wealth was distributed as widely as possible, it would be hard to conceive of a more outrageous reversal of his meaning. Marx gave as his sources the Morning Star newspaper; but the Star, along with other newspapers and Hansard, gives Gladstone’s words correctly. Marx’s misquotation was pointed out. Nonetheless, he reproduced it in Kapital, along with other discrepancies, and when the falsification was again noticed and denounced, he let out a huge discharge of obfuscating ink; he, Engels and later his daughter Eleanor were involved in the row, attempting to defend the indefensible, for twenty years.

None of them would ever admit the original, clear falsification and the result of the debate is that some readers are left with the impression, as Marx intended, that there are two sides to the controversy. There are not. Marx knew Gladstone never said any such thing and the cheat was deliberate. It was not unique. Marx similarly falsified quotations from Adam Smith.

From Paul Johnson, ‘A Capital Lie’ in The Penguin Book of Lies, pp. 238-240

| A photograph of Ulyanov and his wife Nadezhda Krupskaya in late August 1922, taken by Maria Ulyanova. It has been retouched in an attempt to make the telescope, ineptly included in the photograph by Ulyanov’s sister, less like a rifle pointing to Krupskaya’s head (David King, The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia, p. 89). Ulyanov spent the last three years of his life lapsing in and out of insanity. His sister, who nursed him, recorded how he became increasingly paralysed and confused, howling like a wild animal and uttering gibberish such as “Revolution ... help me ... bourgeoisie ... people ... go to hell!” |

|

“Lenin”: The Final Icon

Modern “Marxist-Leninist” groups try to avoid being associated with the disastrous and bloody failure of the Soviet Union by arguing that the USSR was not a Communist state at all. They claim that it was a noble experiment which lost its way when the early death of their innocent hero Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (alias “Richter” alias “Lenin”) gave Dzhugashvili the opportunity to replace Communism with “Stalinism.” This, of course, is nonsense.

In fact Ulyanov, this earthly god of the Left, was no better, and more likely, an even more debased individual than Dzhugashvili. The facts which prove this are not the product of our fanatically anti-Communist brains. Much of the following has only recently emerged from the Soviet archives in Moscow.

We go back to a time before the Russian Revolution, back to Mother Russia in the days before Ulyanov, one of the greatest enemies of the working class ever, poked his bald reptilian head into the world. Vladimir Ulyanov certainly didn’t come from a working-class background as his modern day acolytes try to pretend. His mother came from a wealthy land-owning family of Jewish and Swedish descent. His grandfather on his mother’s side, Srul Moishevich Blank, changed his name to “Aleksandr Dmitrievich” and ditched Judaism for Christianity in order to further his medical career. This clearly worked as he rose from being an ordinary doctor, on his way up the ladder becoming a police district doctor and eventually registering himself as a member of the nobility. The Left tried for years to claim that his grandfather on his father’s side was a serf, but this is a lie. Nikolai Vasilievich was in fact a town-dwelling tailor at a time when only quite wealthy people could live in a town. To find a single working class member of Ulyanov’s family you would have to go all the way back to his great-grandfather, a serf who bought his Asiatic wife. This explains Ulyanov’s Mongolian features.

All Ulyanov’s other ancestors came from wealthy families, not just Jewish, Russian and Swedish but also German. One of his German cousins was Field Marshal Model, also known as the “Fürher’s Fireman,” but for some strange reason Communists don’t like to mention this illustrious direct relative. Ulyanov’s parents were both rich, high-ranking landowners. As well as owning hundreds of acres of land in various huge estates, they also owned serfs – oppressed and exploited workers to give them their proper “Marxist” title.

Of course, a man cannot be held responsible for his parents’ actions, but his own are a different matter. In 1887, Vladimir Ulyanov was expelled from Karjan University for participation in student riots. The family already had a bad name with the authorities because his elder brother had tried to assassinate the Tsar. This incident is blown out of all proportion today. Alexander Ulyanov shadowed the Tsar on a number of occasions and plotted with a group of student terrorists to kill him. When they were caught the elder Ulyanov was condemned to death. Clemency was offered if he would repent, but Alexander did not believe that the Tsar would kill a nobleman, so he refused to apologise and promise not to be a bad boy again. The Tsar very sensibly had him executed.

Vladimir was banished to one of the family estates under orders from the police and tried again and again to be re-admitted to Karjan University. One of his letters to the University authorities included the stirringly defiant request for “Your Excellency’s permission to enter the Imperial Karjan University.” The future “great proletarian leader” also had “The honour most humbly to request Your Excellency to allow me to go abroad to a foreign university,” signing himself “Nobleman Ulyanov.”

Running one of the family farms must have sounded dangerously like real work, so Ulyanov shut himself up in the summer house. There he wrote his first “Marxist” article, snappily entitled ‘New Economic Movements in Peasant Life.’ This goes on and on criticising the evils of capitalism in the countryside, particularly money-lending, leaseholding and the increasing number of kulaks, or rich peasants. But what happened to the family farm while Ulyanov was suffering the agonies of writer’s cramp? He rented it out for seven years to one Mr. Krushvits – a kulak.

In spite of all his grovelling the university refused to re-admit him, but his fortunate family circumstances allowed Ulyanov to study Russian revolutionary leaders and “Marxism” and prepare to take his law exams externally. He passed them in 1891 but seldom practised law. The first time was when he sued a peasant neighbour who had carelessly allowed his cows to graze on part of an Ulyanov estate. Ulyanov may not have had a perfect grasp of J. J. Proudon’s anarchist dictum that “property is theft,” as quoted by Marx (or is that Mordecai?), but at least he won his case. (The second great victory in Ulyanov’s legal career came some years later when he was in exile in Paris. A car knocked him off his bicycle, so he sued the driver and pocketed another “hard-earned” wad.)

Ulyanov moved to St. Petersburg in 1893 and discussed the application of “Marxism” to Russian conditions in illegal revolutionary groups. Ulyanov believed that workers with the aid of the peasantry would overthrow first the monarchy and then capitalism in Russia. In December 1895 he was sentenced to 15 months in prison for being a member of a “Marxist” propaganda circle. He was then packed off to Eastern Siberia for three years. Life there was not, however, anything like the living hell endured by the inmates of the concentration camps which Ulyanov and his colleagues later created for their opponents. The ‘Nobleman Revolutionist’ was exiled to Shushenskoye where he passed the time in long forest walks, swimming, hunting with a rifle or simply lazing in bed. According to one of his letters he acquired a good suntan in the summer and his rations made him put on weight. At one point he even compared his “prison” with Sopitz, a resort in Switzerland where he and his family had formerly gone on holiday.

Ulyanov did have one major complaint about life in brutal Tsarist exile: he couldn’t get domestic help and had to do his own washing and cooking. Left-wing feminists may prefer not to consider if this influenced his decision to get married, which probably took place in this so-called prison in July 1898. In his request for consent to marry he signed himself “Hereditary Nobleman Ilyich.” His various “Marxist” friends who were also “imprisoned” in other areas were able to attend the wedding without even having to ask for permission, as they were free to visit each other whenever they pleased.

The generally believed story that the revolution which took place in Russia in November 1917 was the result of the down-trodden Russian people rising up against their exploiters under the brilliant leadership of Vladimir Ulyanov and Lev Bronstein (known to some as “Leon Trotsky”) is one of the biggest hoaxes ever inflicted upon a gullible mankind. When the Russian Tsar was forced to abdicate in March 1917 Bronstein was working for a Communist newspaper in New York and taking the occasional bit-part in pornographic movies. Ulyanov was in Switzerland, described by a Menshevik colleague as follows:

‘There is no other man who is absorbed by the revolution twenty-four hours a day, who has no other thought but the thought of revolution, and who even when he sleeps, dreams of nothing but revolution.’

Ulyanov was sent from Switzerland into Russia in a sealed train, along with at least fifty of his fellow Bolsheviks, by special arrangement with the German High Command. As Churchill graphically described this remarkable episode, Ulyanov was sent into Russia

‘in the same way that you might send a phial containing a culture of Cholera to be poured into the water supply of a great city... No sooner did Lenin arrive than he began beckoning a finger here and a finger there to obscure persons in sheltered retreats in New York.’

One of those obscure persons was Bronstein, who lost no time responding to Ulyanov’s beckoning finger, chartering a ship in New York and packing it with 275 fellow “Bolshevik revolutionaries” (actually Jews from the Lower East Side of New York City). But when the ship, the S.S. Christiana, reached Halifax, Nova Scotia, the Canadian Government promptly arrested him and impounded the large sum of money he was carrying. The Canadian Government took the view that as Bronstein and his fellow Bolsheviks had openly proclaimed that when they took control of Russia they were going to make a separate peace with Germany, and that as this would mean the use of more German troops against the Western Front where large numbers of Canadians were fighting, they should prevent Bronstein from continuing on his revolutionary mission. Bronstein was held for five days, but then allowed to proceed by a Canadian Government forced to yield to a “world-wide conspiracy.”

Ulyanov had learnt an important lesson from having his brother’s neck stretched: Look after Number One! As he wrote to his sister “We shall not go that way again.” This might explain why, in the months before the Revolution, while the fiery Bronstein was either in prison or at the barricades, Ulyanov put on a wig and hid with the ubiquitous “Zinoviev” (real name either Radomyslsky or Apfelbaum) in a fisherman’s hut until the fighting was over. In this fisherman’s hut and across the border in Finland Ulyanov wrote State and Revolution and directed preparations for seizure of power by the Soviets, the local “parliaments,” in which the Bolsheviks were gaining a majority. Ulyanov had been accused by Kerenski’s Provisional Government of being a German agent, not an unreasonable charge since the Germans had arranged his transport to Russia and were also channelling money to the Bolsheviks. Of the latter Ulyanov must have been aware.

If we were to catalogue every double standard within the life of the great “Communist hero” Ulyanov we would fill a tome the size of a telephone directory, but here’s another glaring example. Today’s “Leninist” groups campaign against the death penalty, arguing that such things are turning western nations into brutal police states – something they affect to oppose. Yet according to Bronstein, who had stood next to him in the Duma (Russian parliament) when the Provisional Government abolished capital punishment, Ulyanov had asked coldly “How will we keep power by sending dissidents to jail?” Ulyanov also approved the setting up of concentration camps for political opponents.

A proclamation made by Ulyanov at the end of December 1917 was: “Let them shoot on the spot every tenth man guilty of idleness.” A few days afterwards he declared that “Enemy agents, profiteers, marauders, hooligans, counter-revolutionary agitators and German spies are to be shot on the spot.” Only a few months earlier, of course, Ulyanov himself would certainly have been included in this list. To those who thought “shooting on the spot” was a bit over the top he asked “Do you think we can be victors without the most severe revolutionary terror?” Nor was the terror restricted to political opponents, the upper classes and the unfortunate Romanov family. In June 1918 capital punishment was formally reintroduced and in July and August alone of that year there were 73 major peasant revolts against the new Bolshevik tyranny. Ulyanov ordered the Tcheka to “instantly introduce mass terror” wherever they encountered the slightest opposition. So it was Ulyanov, not Dzhugashvili, who used terror as state policy and turned Russia into a police state.

The core of the conspiracy which had financed the “Russian” Revolution was the international financial groups linked with Kuhn, Loeb and Company. One of the principal figures was Jacob Schiff, whose grandson admitted had invested $20 million in a revolution which was in fact imposed upon the unfortunate Russians from outside their country. Other names mentioned in this connection are “Parvus” (real name Helphand) and the Ashberg Bank.

A leading member of Kuhn, Loeb and Company was Mr. Paul Warburg who, with his brother Felix, had left Germany for the United States in 1902, leaving behind their brother Max to run the family bank of M. N. Warburg & Co. in Frankfurt. Paul Warburg married Solomon Loeb’s daughter and Felix Warburg married Jacob Schiff’s daughter. Bronstein later married the daughter of another of the wealthy bankers who backed the Bolshevik Revolution, Jivotovsky.

While millions of troops were being torn limb from limb on the battlefields of the First World War, the international financiers were operating on both sides of the fighting lines. Max Warburg, for example, was playing a vital role in Germany while brothers Felix and Paul were doing likewise in the USA. Another comfortable arrangement at this time was Ulyanov’s, tucked up cosily in neutral Finland or Switzerland with his Jewish wife Krupskaya, so safe that they could leave their door unlocked overnight so that any tired passing Reds could doss on their couch.

Following the imposition of the Bolsheviks upon the Russian peoples, and the British acceptance of the Zionist project for Palestine, the Schiffs, Warburgs and their international associates took the necessary steps, including the entry of the United States into the conflict, to bring the First World War to an end. These financiers were represented on both sides at the Versailles Peace Conference. British Prime Minister Lloyd George later wrote:

‘The international bankers swept statesmen, politicians, journalists and jurists all on one side and issued their orders with the imperiousness of absolute monarchs.’

At Versailles the American President Woodrow Wilson changed his attitude on a vital issue after he received a telegram from Jacob Schiff. Schiff and his associates insisted upon the recognition of the Bolshevik Government in Russia and supported the first step towards the creation of a World Government, the League of Nations.

Various sources, including a tiny booklet by Eric D. Butler entitled Censored History

|

|

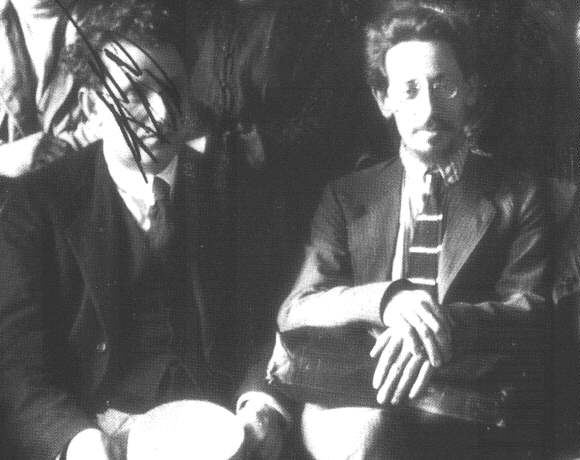

Grigorii “Zinoviev” (real name either Radomyslsky or Apfelbaum) seated next to Yakov Sverdlov at the Fifth “All-Russian” Congress of Soviets in Petrograd, July 1918. “Zinoviev” has been defaced as an “enemy of the people” in this photograph, which was recently found in the Soviet archives. Although he was regarded by the Mensheviks before the Revolution as “Lenin’s mad dog,” “Zinoviev” objected, along with Lev “Kamenev” (real name Rosenfeld), to the October 1917 policy of armed insurrection. “Traitors and strikebreakers of the revolution,” Ulyanov called them. After the assassination of “Uritsky” (real name Radomislsky or Padomilsky) and Ulyanov’s close call, “Zinoviev,” as chairman of the Petrograd Soviet, was thrown into blind panic. He feared that the end of the revolution was at hand and responded with terrible cruelty against “bourgeois elements.” Launching the Red Terror in Petrograd, he declared:

“Zinoviev” was expelled from the Communist Party in 1927 for his opposition to Dzhugashvili and was twice exiled. He was one of the main defendants in the Moscow show trials and was shot in 1936. David King, The Commissar Vanishes; ironic quotation marks added |