While they took gold, treasure and merchandise when they could, the real booty of the Barbary raiders was people. In all, this little-known but massive white slave trade involved the capture of almost one-and-a-quarter million Europeans – many from Britain’s south coast.

On one occasion, the Barbary pirates sailed away with the entire congregation of a Penzance church. When James I sent a fleet to demand the return of Christian captives (unsuccessfully), the horrified public learned that more than 25,000 white slaves were held in the Barbary states – pirate kingdoms stretching from Egypt to the port of Sallee on the Atlantic coast.

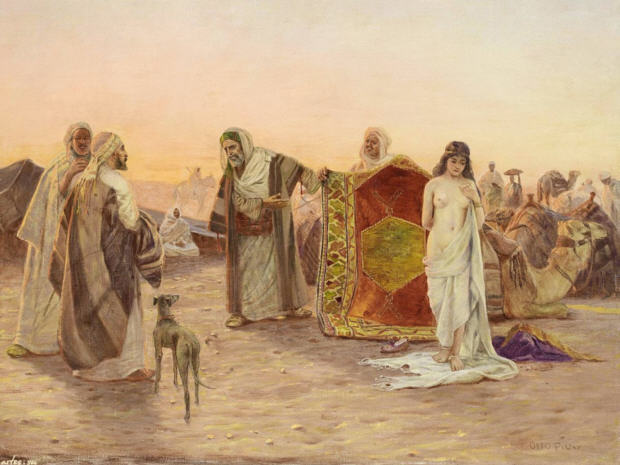

Popular pamphlets described the horrors awaiting prisoners in graphic detail. They ran particular riot over the fate awaiting female captives, painting in lurid colour the unmentionable vices of the masters to whom these unfortunates were forced to submit.

But the truth was rather different. Good-looking European girls and women were prized commodities and were therefore carefully treated.

Their teeth and breasts were inspected and, sometimes, their virginity was established too, before being offered to the Sultan or bought by some rich man as the ornament of his harem – a life regarded as the height of bliss by many local women.

The youngest and most beautiful, like an Englishwoman who became the wife of a Sultan of Morocco, were reserved as spoils for the rulers of the Barbary states.

The choicest of all were sent by these rulers to their supreme head, the Sultan of Turkey, Allah’s Shadow Upon Earth, ruler of the great Ottoman empire.

Male captives, however, had an unhappier fate. Most could only look forward to a life in the galleys, chained to their oars. For the Barbary empire was run on slavery: piracy was a profitable business and, in the early years, oar-power was the easiest way to achieve success.

In the Mediterranean, towers were built to watch out for the corsairs. Merchant ships travelled in convoy, using black sails and going without lights to avoid detection at night.

But during the early part of the 16th century, whole fleets of corsairs would attack coastlines, carrying off thousands of captives. At one time it was said there were so many slaves awaiting sale that you could exchange a Christian for an onion.

They ranged so freely that they once snatched 400 people in a raid on Iceland. More often, though, they raided villages on the English Channel coast.

They attacked with impunity, for in the early 1600s, Britain had little naval strength; the King, on a collision course with Parliament that would lead to the Civil War, had difficulty in raising money for ships.

A typical raid was the one on June 19, 1631, under the command of the infamous Barbary captain Murat Rais. He anchored off Baltimore, a village in County Cork, and despatched four boats laden with warriors who lay hidden until they reached land.

There, they sprang ashore and rushed to the village, setting light to the thatched cottage roofs, grabbing what goods they found and seizing their real booty – the people who lived there.

Of the 109 people taken, 80 were women and children – an unusually high proportion, as in general nine out of ten captives were men. The following day, the pirates set sail, arriving in Algiers on July 28.

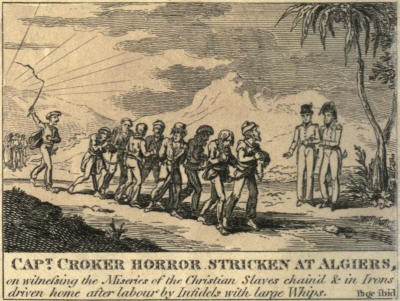

There, the prisoners were put in cages; as one, James Wadsworth, wrote: ‘We were crammed like capons to be fattened for sale.’

Those who would fetch high prices – gentlemen good for a ransom, beautiful women, skilled seamen and craftsmen – were sold individually; the rest went in batches, largely as galley slaves. The vessels they were destined for were light, long, sleek wooden boats, as different from the Dutch merchantmen they often plundered as a skiff from a barge.

And these galleys were kept in superb condition. Raids were brief, so that every month or so the galleys could be beached in their home port and have their hulls scraped clean of barnacles, then waxed so that they could slide swiftly through the water.

Powering the galleys were rowers who sat chained by their feet to benches, four or five to each of the 20 or 30 15ft oars. On a ramp down the centre strode the overseers, lashing them with whips made from dried, stretched bulls’ penises.

Sitting in the stern were up to 140 warriors armed with bows or, later, muskets – plus their preferred weapon, the two-edged scimitar. In the bow were a few cannon. The life of a galley slave could be bitterly hard. There are stories of slaves made to row ten, 12 or even 20 hours at a stretch. ‘If one falls exhausted over his oar (which is quite a common occurrence) he is flogged until he appears to be dead, and is then thrown overboard without ceremony,’ wrote a Frenchman who had served in a galley.

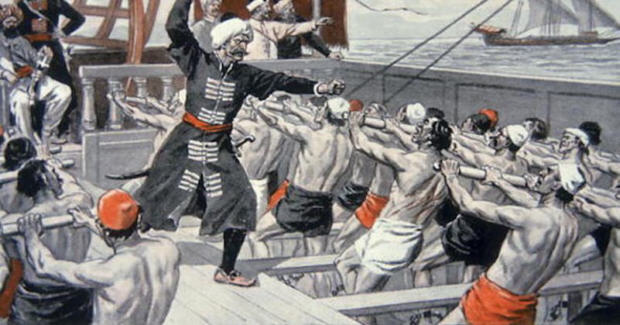

Attacks were always carried out in the same way. Spotting the prey – one of the clumsy merchantmen that traded constantly across the Mediterranean – the galley sped towards it. The cannon in its bow were used not so much for attack but to clear the deck of the target ship prior to boarding.

Then the turbanned and bearded warriors, shouting war cries and hurling abuse, would spring aboard to rampage through the ship – cutting, slashing and slicing at any opposition.

Once in control, the pirates’ technique was equally swift and efficient. Boxes were broken open with axes, passengers were stripped, and those suspected of swallowing their money were turned upside down and shaken until the coins came out. Then the cross-questioning began – with, if necessary, torture by beating on the feet – to discover the hiding places of treasure, and to find out the rank and wealth of the passengers so that the rich among them might be ransomed.

Attempts to fool the pirates usually failed. Even if a nobleman changed clothes with his valet, the corsairs would look at his hands to see if they were those of a worker.

Not all galley oarsmen were slaves. Some were free Christian seamen drawn to the Barbary coast by the prospect of booty.

For after the ship’s owner and port officials had received their share, and the expenses of the voyage had been defrayed, the rest was divided between the crew – with the captain receiving 12 times as much as a sailor, who in turn received twice as much as a soldier.

While the life of a galley slave could be hell on earth, it was not necessarily so. Many slaves were bought as household servants or clerks, borne rising to positions of importance and indeed affection. On the back of this slave trade was another thriving business, ransoming. Some captives were bought for their potential ransom value, and one order of Catholic priests even specialised in raising funds and negotiating releases.

In Britain, ransom money was generally raised outside churches – but with a labourer’s wages at £20 a year, and the cost of a male slave £40, few of the poor were ever ransomed.

Sometimes, slaves were able to finance their own ransoms by establishing a business sideline.

Others converted to Islam. For, by renouncing one’s religion and ‘taking the turban,’ a Christian sailor in the galleys could throw off his chains and become a free seaman – with a share in the booty.

When the largest-ever hoard of Islamic gold coins and jewellery, along with several cannon, was discovered by amateur marine archaeologist Neville Oldham on the seabed in Salcombe Bay, but with no trace of a wreck nearby, it seemed a mystery.

Yet several artefacts found nearby – Delft pottery and pewter, and a clay pipe from Edam – seemed to hint at a Dutch merchant vessel.

When Oldham and his fellow divers found a pewter bowl with the initials M.R. on the bottom, they hoped to trace the owner through shipping records. But no name with these initials existed within the right timespan.

Gradually, they became convinced that the gold and cannon had come from a Barbary raider. After all, the gold jewellery had been cut in half – standard procedure when dividing up loot between a ship’s crew. The vast amount of coins could be explained because, since Islam forbids usury, there were no banks in which successful corsairs could deposit their cash.

Even the last piece of the jigsaw, the initials M.R., could point towards the same explanation. One of the most famous corsair captains was Murat Rais, a renegade Dutchman who – like several others – had left his wife and children and become a Moslem for the lucrative excitement of life as a corsair commander.

None of them hesitated to capture fellow Europeans for sale (it was Murat Rais who had carried out the raid on Baltimore).

For the corsairs, the beginning of the end for their trade in human flesh came in 1816 when the Royal Navy, now the most powerful in the world, pounded Algiers with its guns, forcing the release of 1,600 slaves.

It was a French fleet that, by occupying Algiers in 1830, brought the activities of the Barbary corsairs to a final and definite stop.

Adapted from Anne de Courcy, ‘Sex Slaves of the Sultans,’ Daily Mail, 4 January 2003. The article introduced the BBC’s Timewatch – White Slaves, Pirate Gold broadcast on 10 January 2003.