|

|

| Cannibal Culture | |

|

Selected excerpts from Jens Bjerre’s The Last Cannibals on primitive beliefs and customs New Guinea |

Cannibal Courtship and Customs (3)

Soon after the girl has been initiated, she looks around for a suitable husband. Among the Kumans, it is, as a rule, the girls who take the initiative in this matter and not the men. The girls are already interested in boys at the age of eleven or twelve, whereas the boys show no interest until they reach the age of puberty. There are various round games and ceremonies designed to get the young people to know each other and to sort out potential marriage partners. There is no question of a man buying a wife against her will. There are two particular courting ceremonies where the young people meet in this way. One is a semi-private party called Kango; the other is a public party called Goanande.

When a young girl gets interested in a young man she invites him home to a Kango. If the young man accepts the invitation, he goes to the girl’s hut after dark, often accompanied by a friend, if it is the first time he has been to such a party. The mother is always present. After a brief introductory conversation, the two young people sit next to each other, holding hands. The boy then starts a song in a high-pitched voice and the girl joins in. They sway their bodies in time to the music and sometimes they kiss during these movements. The songs are traditional ballads in praise of nature, and sometimes, too, of human nature. When the song is over the young couple chat and laugh and, perhaps, start a new song. The boy may also recite a few magical love phrases to increase her warmth for him. Towards midnight the mother, who has been present all the time, will drop a hint that she wants to sleep. If the boy is tactful he will get up and go home. If he does not want to go, tribal etiquette forbids them to take further action and he can stay on until daybreak. If the mother finally drops off to sleep the couple may make love, although this behaviour is contrary to the rules of the tribe. Boys and girls can go to many parties of this kind with a new partner each time, and thus they gradually discover the one they like best. It sometimes happens that a couple meeting by chance during the day will start a kango in public, with a crowd of laughing and sympathetic lookers-on.

Kuman behaviour is altogether natural and uninhibited. When friends of the opposite sex meet, they do not greet each other by gestures or shaking hands; their greetings are much more intimate and thorough-going: they pat and stroke each other often in intimate places, accompanying their actions by affectionate phrases. Married men, too, indulge in kango parties, not with their wives but with other girls. The result, sometimes, is that they collect a new wife; sometimes the result is a brawl in which his angry wife breaks up the kango. Kango time, for a girl, ends once she has married.

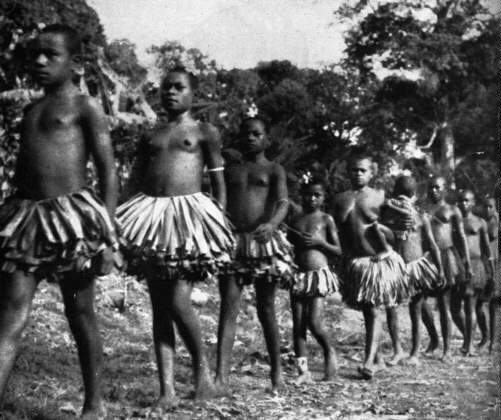

The other love feast, the Goanande, is arranged by marriageable young men and women from various groups within the clan. Boys and young married men equally take part, but the poor married girls are not even allowed to be spectators. The boys sit in a row, with their backs to the wall; the girls in a row on the opposite side, a girl opposite each boy. After a couple of songs, the boys move up a place so that they all get a new partner. During the session, which goes on all night, the boys have partnered all the girls several times and may have got to know them pretty well. A couple who feel specially attracted to each other can leave the party and set up a kango on their own...

When a young man has participated in several kango and goanande feasts, and has chosen (with her consent) the girl he wants to marry, he asks his father or elder brother to kill a pig and give it to the girl’s parents. After that the young couple are considered engaged. The night before the girl moves into the young man’s family, there is a farewell party for her attended by her relations and those of the man she is to marry. Wearing no bridal finery the girl sits in the middle of the circle of guests, while the women perform a ritual cleansing of her body...

A couple of days before the wedding ceremony some of the girl’s male relations visit the young man’s home to inspect the presents he has collected for the girl’s family: stone axes, steel axes, jewellery made of sea-shells, and one or two pigs, which will be killed on the wedding day. If they find the presents sufficient, they discuss what presents the girl’s family will supply, partly on the wedding day and partly in the future. The exchange of presents is thus a token of unity between the two families. On the wedding day the young man goes with his family to the girl’s home bringing the presents and the pigs that are going to be slaughtered for the feast. The presents of both families are laid out in two heaps in front of the girl’s home. The wedding ceremony now proceeds. On one side of the presents the young girl and her family stand together; on the opposite side stands the bridegroom’s family. The bride’s father or uncle calls forward a man and a woman from the groom’s group, and these go over to the girl, take her by the hand and lead her over to her husband. By that act she has left her family. The two young people are now man and wife. Then the pigs are slaughtered, and a riotous feast is held.

Among the Kumans present-giving is frequent and popular. Generally the exchange of presents is a token of friendship between persons or groups; but even within families there is a constant exchange of presents between a man and his parents or his in-laws. It is always assumed that the presents exchanged shall be of equal value. Presents are also ‘lent’ to a young man so that he can put up a good show for his wedding or to show sympathy in case of death or illness. If a man is offered a present of such value that he has no immediate hope of returning one equally good, he may not refuse it. That would be a deadly insult to the donor. A mean man who never gives presents has no friends, whereas a man who habitually gives presents of higher value than the ones he receives is highly esteemed in the village.

Presents are expected and given, as we have seen, for immaterial things such as songs and stories. There are in every clan men and women of surprising imagination and good memory, who, in this way, amass substantial wealth by singing and telling stories. The story-teller knows the names of every bird and plant in the neighbourhood, and has an encyclopaedic knowledge of the traditional laws of the clan. Presents are given, too, as a form of compensation; in requital of an oath or an insult. If a woman, in a fit of anger, destroys some of her own property, she can demand compensation from the person who infuriated her.

Jens Bjerre, The Last Cannibals, Michael Joseph, 1956 pp. 131-135