|

Blackshirts in Hull and SouthportExcerpts from Blackshirts and Roses by John Charnley, particularly about the Blackshirts in Hull immediately before WWII |

Southport: Tried and Fined for a Non-Existent Offence

During the early part of this campaign Mosley addressed a meeting in Southport at the Floral Hall. Being a holiday resort, Southport was not expected to produce a rowdy meeting, and the audience was quiet and attentive. For some reason which I never learned, there had not been the customary blaze of pre-meeting advertising. The usual procedure was to use the public hoardings with a head and shoulders of Mosley with folded arms and a semi-profile head held at a slightly uplifted angle on a background of crossed flags and carrying the simple statement ‘Mosley Speaks’ with the time and place of meeting.

Only a few of these posters appeared and I was concerned at the lack of publicity. As propaganda was now my department I felt responsible and hit upon a solution. On the Saturday before the meeting, I would repeatedly tour the town on my motor bike with a suitably inscribed poster on my back, in the nature of mobile ‘sandwich man.’

One of our members who had a flair for this work prepared the poster which was pasted on a sheet of hardboard and securely strapped to my back and off I went on my tour. I kept as close to the kerb as I reasonably could, and only travelled in low gears. It was a huge success and created something of a sensation in the town centre, particularly as I was doing a continuous tour, and wearing my Blackshirt uniform.

After about half an hour I was flagged down by a policeman who, obviously acting on instructions, told me that I was probably breaking the law and advised me not to continue. I asked him what law I was breaking and when he could not tell me I replied that I intended to continue. On my next ride down Chapel Street four uniformed policemen, two from each side of the road prevented my driving by. One was a sergeant who warned that if I continued I would be arrested and charged with “Obstructing the police in the execution of their duty.”

If I had been as belligerent then as I was later to become I would have defied them and courted arrest, knowing that the resultant publicity would have become nationwide, but at the time I felt that I owed some loyalty to my employer, and agreed to discontinue my publicity campaign. I was told however, that I would probably be charged with an offence under a section of the local bylaw, and my poster was confiscated as evidence...

Some time later I received a summons to attend the Court of Summary Jurisdiction to answer a charge of contravention of a local bylaw. When I attended the Court I was charged with ‘Driving a mechanically propelled vehicle on the King’s Highway for an unlicensed purpose,’ to which I pleaded guilty, my objective being to get away with as small a fine as possible.

In my defence I quoted a number of known instances where other vehicles including transport operated by the local council were in breach of the same bylaw, citing specific instances such as advertising posters for various functions, some held in the same council owned building, where we had held Mosley’s meeting. The chairman of the magistrates brushed this aside and refused to accept it as exoneration. I was found guilty and fined a pound.

It was obvious that it had already been decided that I was to be found guilty, and I found out later that there was no such offence as that under which I had been charged. There were two classified breaches of the transport law, one ‘Driving without due consideration for other road users,’ and ‘Dangerous Driving,’ and under neither of these could I be charged. From that day my belief in British Justice was minimal (pp. 52-55).

|

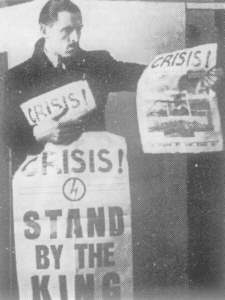

“He had no enthusiasm for the job and in any case you cannot continue fighting for a man who will not fight for himself. When an opportunity is irretrievably lost do not waste time in useless regret.” Mosley on the abdication of King Edward VIII (p. 69) |

Hull: The Riot on Corporation Fields; London: The ‘Battle of Cable Street’; Mosley’s Return to Corporation Fields

I had tried, through McKecknie, to secure a Leader’s Meeting in Hull but with no success to date. I got John Beckett for a medium-sized hall, and the meeting started off rather rowdy. It was held in the Fulford Rooms on Beverley Road, and was the first time that I met Dick Bellamy, National Inspector, working from offices in Corporation Street, Manchester. Due to continued interruptions and the clamour of constant scuffles an elderly lady wanted to leave. I was in charge of the exits onto the main road. Dick escorted the lady to the rear of the hall and asked me to open the door. I knew we had a very rowdy crowd outside and I expected trouble. When I opened it we were met with a hail of bricks, and Bellamy was so incensed that he dashed across the wide footpath waving his arms and shouting “Oh you swine, you despicable swine!” The police were in evidence and assisted the elderly lady away from the entrance, but Dick and I were involved in more fighting before we were able to return to the hall. From that moment he was someone special in my life. Only one other man has made a greater impression me and it was especially important that I joined with Dick a few years ago to talk of our association with Oswald Mosley in the BBC television documentary ‘Britain in the Thirties.’

As a youth Dick had led an adventurous life as a ‘jackaroo’ in the Australian outback and a coffee planter working among cannibals in New Caledonia. He told of these exciting times in two books: The Real South Seas and Mixed Bliss in Melanesia. Dick was a superb story-teller and the latter book was described by the Observer as “The best travel book of the year.” He returned to this country in the early 1930s and was shocked by the poverty and conditions he found. Within a few months of its foundation, Dick joined British Union and eventually became Senior Staff Officer in charge of Northern Headquarters based in Manchester. He was selected as our parliamentary candidate for Blackley in readiness for the General Election of 1940 that never came. Dick described his period as National Inspector for the region as “probably the happiest time of my life.”

It was eventually agreed that we were to have a Mosley meeting in Hull. The local authority refused us the use of the Guildhall and the management of the Astoria Cinema pulled out of a verbal agreement following threats of violence and possible damage to the cinema.

|

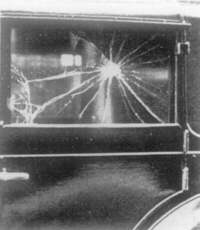

The only alternative was an open-air meeting. I have been at Olympia, Holbeck Moor, Leeds, and Royal Mint Street, London, all of which were rough, but none was so rough and tough throughout the whole of my seven years in the pre-war movement than at Corporation Fields, Hull, in July 1936. The trouble which developed, and the size of the opposition that had assembled there before our arrival, was absolutely beyond my comprehension. It was obvious before the meeting started that there was going to be very serious trouble. But the opposition was so vicious that it is difficult to make people who weren’t there understand and appreciate the reality. At this meeting every type of weapon was used, and the fight went on for over an hour. It was alleged that an attempt had been made on O. M.’s life, and a bullet hole was certainly found in the windscreen of his car. |

|

At the height of the battle, Yorkshire National Inspector, Peter Whittam yelled out at the top of his voice, “This can’t go on. Get your bloody belts off!” We did, and using them in self-defence, kept our frenzied assailants at bay.

The press later alleged that we had attacked the crowd with steel-buckled belts. We did not attack the crowd. I was in charge of that meeting. I wanted new members, and to get them I had organised that meeting so that the audience could listen to Mosley explaining our policy. How I wish I could dispel the lies that were so often told about us!

The Chief Constable eventually arrived at the meeting, and advised Mosley, Francis-Hawkins as the administrative organiser, and myself as the local organiser, to call the meeting off otherwise he would use his powers to read ‘The Riot Act.’ Mosley got down from the coal cart which we had been using as a platform and asked me to arrange for a departure from the field.

The crowd was still very hostile, and I had to try to arrange an orderly withdrawal. We formed up into a column three abreast ready to move off. It fell to me to lead it since I was in charge and had to take the visiting stewards back to the garage where their coaches were stationed.

We were completely surrounded by a howling mob literally screaming for our blood, and I was frightened. If I said otherwise I would be a liar. I was scared, and Mosley knew it. He tapped me on the shoulder and said, “Which direction do we have to go?” And I pointed the way. “Right,” he said, “start marching in that direction and I promise you, that provided you show no fear, that crowd will open up and let us through. I know that you can do it, and don’t forget that I am right behind you.” He looked at me, nodded his head and said “Now,” and I moved.

How I did it I don’t know, there were a few scuffles, and once we had to stop to re-form. We got off that field carrying our wounded and marched back to our headquarters, half a mile away. We had over twenty hospital cases for the out-patients department, but fortunately no one was kept in. The Reds, however, had over a hundred. We had given a good account of ourselves!

When we left the field the police collected the opposition’s weapons from the battle ground. They included brush staves with six-inch nails in the end, bicycle chains, lengths of ship’s steel hawser, knuckledusters, raw potatoes studded with razor blades and thick woollen stockings with broken glass in the heel and foot.

Subsequent official reports completely exonerated the Blackshirts, placing the blame fairly and squarely on the Communist opposition. You will read little or nothing of this in the “histories” and “social documentaries” written and broadcast by their supporters and apologists within the media and British Establishment.

I quote from a report made by Inspector J. Holmes (HO 144/21060 92242/20, folio 154):

“The Fascists were not to blame as nothing was said or done to provoke the crowd. They did not interfere with anyone until bricks and other missiles were thrown, and one of the party seriously injured. Several others received minor injuries.”

Another officer, Sgt. T. A. Sawdon reported (folio 160/161):

“owing to the violence of the crowd it was impossible to take anyone into custody for these assaults, as we had our work cut out to protect ourselves. At no time did I see any action on the part of the Blackshirts that was likely to provoke the crowd into the way they acted.”

The Blackshirt “seriously injured” had been hit in the face with a half-brick, and when he fell to the ground, received a second brick on the head. Another Blackshirt, B. H. Taylor from Doncaster, suffered “severe head and face injuries,” while W. A. Milligan from Sheffield sustained “serious head and facial injuries. Front teeth split from edge upwards to the roots, inner pulp being damaged. Crushed tooth nerves. Teeth will eventually have to be removed.”

In all, 8 of the 21 Blackshirts injured had head wounds, one of them being John Charnley.

I was working at Jacksons at this time and the next day I was on 6a.m. start. There were many strange looks but no condemnatory remarks. One man said “You must have a lot of guts,” and that pleased me.

I finished my shift at two o’clock, and whether out of bravado or because I was stupid I carried my speaker’s stand down to the Labour Exchange and held a short meeting. I met with no opposition, probably because my action was not expected.

Shortly before the meeting, on the Corporation Field, my two brothers and I discussed the idea of renting suitable property which we could use not only as a home but also as suitable headquarters. We would jointly become the tenants and the office rent now being paid for headquarters could be transferred as a contributory rent income. I discussed the idea with Francis-Hawkins and he was agreeable. We soon found a suitable property on Spring Bank not far from where Syd and I were now living.

It was a large three-story building, with extensive room space on the ground floor and an abundance of living space above. The ground floor was utilised as office, club rooms and kitchen. It was a good site and a good address and the property was in fine condition. We had a dormitory on the top floor where we often accommodated visiting officials for overnight stops. Shortly after moving in, two brothers, both of whom were members, also joined us as tenants.

So the three brothers were together again living under the same roof. Peter had now left Melias and joined a local firm – the one that I also worked for – he on the grocery side of the business, me in the bakery. A long-standing friend of Peter used to come in twice weekly to see to the cleaning and laundry, and on these days would also cook a hot meal for us. Later she was to become a good friend to my wife.

We settled into a routine. Unless we were acting as stewards for a Leader’s meeting in another town, Sunday was always free of local politics. Monday evening was always devoted to a member’s meeting in a large room used for this purpose, when the programme of the week would be discussed and agreed. I had a very good treasurer in Jim Bellini, whose accounting was always detailed and up-to-date. It was his responsibility to collect subscriptions from active members, and to arrange his own system of collecting subscriptions from non-active members, who seldom attended headquarters. He was also responsible for the ordering and distribution of our weekly paper for street sales, and delivery to regular readers. He was a member of the army reserve, and I sorely missed him when he was recalled to his regiment shortly after Chamberlain’s Guarantee to Poland.

The duties of treasurer were then taken up by one of the lodger brothers, Vic King. Although not arrested at the same time he was later to join me in Walton Gaol. He still lives in Yorkshire and we correspond, but infrequently.

National Headquarters produced a wide selection of pamphlets dealing with the many different aspects of our policy. Mosley was the only politician, up to present, who had a detailed policy for every section of trade, industry and commerce. There was not a single problem of national life that he had not analysed and evaluated. In this he was and will remain unique.

These policy leaflets were available at a nominal charge, and we would carry out house-to-house distribution, including back copies of our paper to stimulate interest in our policies.

Thursday evenings, weather permitting, would be devoted to a street meeting. Hull had many sites for permitted open-air meetings, my favourite site being Baker Street, a side street of Prospect Street and close to the city centre.

In the summer months we would often cycle out to either Beverley or Driffield, both small agricultural towns, and on rare occasions would even go as far afield as Market Weighton, but for this we had to lay on motor transport.

I could no longer afford to run a motor-bike and had sold mine shortly after arriving in Hull. Twice we even travelled across the Humber to hold meetings in Grimsby, but we discontinued them because it necessitated a race back to New Holland to catch the last ferry to Hull.

Saturday nights were devoted exclusively to street sales. We would have anything from six to a dozen members on selected sites from 7.30 to 9.30, just enough time left for a quick drink before the pubs closed!

The Communist Party influence in Hull was greater than anywhere outside London, with the possible exception of Glasgow, and it very often made itself evident at our open-air meetings.

As for ourselves, we attracted the widest possible range of people into the Hull branch of British Union. A very large proportion were working class, many – like our Communist opponents – connected with the docks.

There were also small businessmen, a couple of solicitors, even a barrister, two dentists, two or three doctors – the widest spectrum of the community. Throughout its life, British Union drew its support and active membership from every strata of society. Mosley attracted people towards him like a magnet, and it didn’t matter what section of life you came from.

The old saying, “Once with us, Always with us” proved to be very true in my long experience. I have never come across anyone who, once having declared their loyalty to Mosley, ever became violently anti. Quite a number were apathetic, particularly during the war years and after, but overall, once with Mosley, always with Mosley.

|

In the autumn we took time off from local activities to take part in the BUF’s Fourth Anniversary demonstration which was to take place in East London which was to become the media’s ‘Battle of Cable Street.’ Several thousand Blackshirts were to march from the Royal Mint to Limehouse, Shoreditch, Bow and Bethnal Green in each of which Mosley would speak. For weeks Communists agitated to prevent it taking place and on the day, October 4th, they erected barricades in Cable Street and other nearby streets, and fierce battles developed with the police who went in to clear them. To prevent further disorder, the Police Commissioner, Sir Philip Game, after securing the Home Secretary’s approval, ordered the march to be called off, and Mosley, lined up with his Blackshirts half-a-mile away, and whose maxim was ‘uphold the law until we change it,’ marched with his thousands in the opposite direction to be finally dismissed on the Thames Embankment at Westminster. The mass of Mosley’s men had not been involved in the fighting except for a small number who were early arrivals at the meeting place where they were met by hundreds of Reds armed with a variety of weapons, and we were to arrive in the thick of it. |

|

Peter Whittam and I had travelled down overnight with Blackshirts from Hull and Leeds in our Bedford trucks we named our ‘agony wagons,’ and on arrival the street fight was at its height and I saw my old friend Tommy Moran go down from a blow to the head from what looked like a pickaxe handle – as it turned out to be, covered in barbed wire. He appeared to be badly injured with blood pouring from a gash high on the forehead and across the scalp. To my amazement within minutes I saw him rise from the ground, blood seeping from a roughly bandaged head, and re-enter the fray putting many of his opponents to the ground. We won that scrimmage and made our way to our assembly point. It always surprises me that in the heat of battle one seldom experiences fear, and the example and sheer guts of Tommy on that occasion never loses its clarity. He was a great fighter and a source of constant inspiration. After dismissal on the Embankment many Blackshirts made their way to the BUF National Headquarters in Gt. Smith Street where Mosley from an upstairs window spoke to them in words never to be forgotten. “We never surrender” he said. “We shall triumph over the parties of corruption because our faith is greater than their faith, our will is stronger than their will, and within us the flame that shall light this country and shall later light the world.” |

|

The Communists and their left-wing allies portrayed it as ‘great rising of East London workers against Mosley’ but the truth was that the mobs had been gathered from all over Britain and this proved to be the catalyst which created massive support for Mosley and British Union in traditionally patriotic working class East London.

Two weeks later Mosley addressed cheering thousands at several massive street meetings in East London. Called at a few hours notice there was not a sign of those that ‘stopped’ Mosley at Cable Street and six months later Blackshirt candidates polled nearly 20 per cent of the votes in the LCC elections in those boroughs through which he had been prevented from marching on October 4th.

As a consequence of the Communist organised street disorder, Parliament passed the Public Order Act making it illegal after the end of 1936 to wear political uniforms in public which left me feeling very incensed. It was a political act, pure and simple, directed exclusively against our Movement in the hope of putting a break on its appeal.

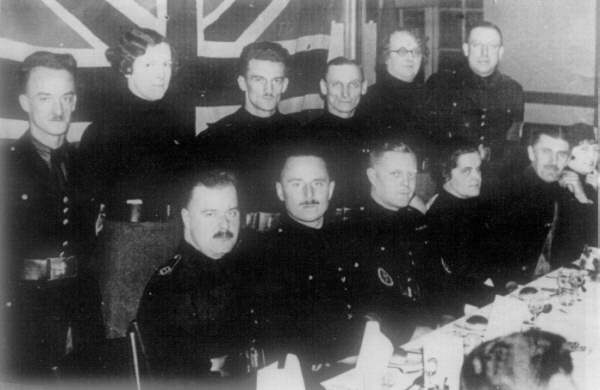

I was most pleased to wear my uniform for the last time on a very special personal occasion. The BUF had not contested seats in the 1935 General Election but decided to choose candidates for the next, which could not be expected before 1940, and much to my surprise I was asked to stand in the Hull East Constituency. We already had a sub-branch there under the leadership of Frank Danby, a devoted and indefatigable worker and I agreed to be adopted, and we had a celebration on December 22nd at the Metropole, a large meeting room.

Mosley and Director General Francis-Hawkins attended as guests and it was a very proud moment when Oswald Mosley made the after dinner announcement. I don’t remember much of my reply except the closing words. “When Mosley leads, what is there for me but follow?” I am still following him and shall continue to do so until the end of my life.

In his speech Mosley also referred to the meeting at Corporation Fields saying “Always we come back and always we win, and always in the end we achieve our objectives... as in the end the Blackshirt Movement will achieve power and save this country.”

And back he came in June to Corporation Fields, almost a year after our 1936 battle, and spoke to a police estimated crowd of 10,000. A small bunch of Reds were no more than a nuisance value and Mosley led a march from District Headquarters and back again afterwards. He promised he would be back. He always kept his promise.

As I have said, 1937 brought the banning of the Blackshirt uniform which at the time I had considered to be essential to our continued progress, and I pondered on ways whereby we might legally overcome it. I felt that the uniform helped to sell our weekly paper as it made us distinctive and stimulated attention.

We used to have armbands on the sleeve of the uniform and I assumed that we might get away with wearing them on civilian clothing. A number of us wore them for our usual Baker Street meetings, but at the conclusion of one the police sergeant in attendance warned me that if we wore them again he might be instructed to charge us with breaking the law.

I thought, or rather hoped, that this was only a threat without any follow-up. We adopted the same tactic the following week and on this occasion I was allowed to finish the meeting only to be arrested and taken to the Central Police Station in Alfred Gelder Street. There I was charged with contravening the Public Order Act, but allowed to leave having been told by another sergeant of police that I would have to answer to a summons.

The summons duly came, and I had to appear before the local Stipendiary Magistrate, Mr. MacDonald. I was defended by a counsel provided by London, and during the process of the hearing I was asked for comments in my own defence.

I asked permission to ask the Stipendiary a question, and my question was: “If a number of men wearing striped trousers and bowler hats and carrying umbrellas attended a Conservative Party meeting, would it be considered that they were wearing a political uniform?” This was in answer to the preamble during which the magistrate had said that we were similarly dressed, in that we were all wearing armbands carrying the motif of a political party. As of course we were. The armband carried the symbol of British Union, which was The Flash and Circle.

The magistrate told me not to be insolent to the court. In his summation he said that as the badge on the armband was the accepted symbol of a political party, the wearing of that badge by more than one person at a political gathering constituted, in his opinion, uniformity of dress and as such could be lawfully construed as constituting a breach of Parliamentary Legislation.

I was found guilty and fined ten pounds, then equal to one month’s wages. Parliament was guilty of deliberate subterfuge. As MacDonald said, “Parliament did not define a political uniform in its legislation and it had been left to the court to interpret the law.” I became less and less impressed with “Democratic” integrity. The Act had clearly been passed in the vain hope of stunting us (pp. 70-81).

Anti-Jewish Activity in Hull

While British Union was not an anti-semitic movement, numbers of our speakers were. To some extent this could be said of me, though my remarks from the platform were always directed against the behaviour of a proportion of Jews, and not attacks on Jews as a whole. My attitude, in fact, was one of response rather than attack, and in the years after the war I was to make a number of Jewish friends in my business life.

There was no mistaking the type of Jewish opponent we were up against in the ‘30s however. The men who threw me through the Southport shop window in 1933 were Jewish, and it is a matter of record that Jews figured excessively in the convictions for assault on our members, including women and girls. It is also accepted that Lord Rothermere’s withdrawal of the Daily Mail editorial support for British Union in the summer of 1934 was brought about by the threatened loss of Jewish advertising. This pattern, it should be noted, was established before Oswald Mosley had as much as referred to Jews in a public speech.

Against this background, it is hardly surprising that by the end of the ‘30s anti-Jewish feeling became more and more pronounced among our members. Some of our supporters took advantage of blackout conditions to institute a series of covert attacks against Jewish-owned shops in the town [of Hull], in an attempt to relieve their feelings of frustration during the period of the phony war.

I realise that reporting this will not rebound to our credit. These actions were not of a serious character, and consisted of sealing the door locks of the shops with an infusion of plastic wood which overnight would set and thereby prevent the insertion of a key to unlock the door. The locks then had to be sprayed with spirit to dissolve the plastic.

These incidents had been reported to the police. I discovered one night that some of our members had gone into the city centre intent upon a repetition, and I received a ‘phone call tipping me off that the police were out in force to catch the culprits.

I immediately set off on my bike and after some time I found three of our members, but they only had one tube of plastic which they had used once.

I took it from them and put it in my pocket. I was about to mount my bike and leave when a number of police officers appeared out of the blackout. “There’s Charnley. Get him, Get him,” which they proceeded to do. My bike was left in the street, and I was arrested and taken to the Central Police Station. I had not thought to throw the tube away, and of course my explanation for my possession of it was not believed.

After being detained in a police cell for about three hours I was allowed to go home. My wife already knew from the members who had returned to our headquarters where I was, and was very relieved to see me on my return. I was later charged with malicious damage to property and fined ten pounds (pp. 90-91).

The War’s End; Open Debate and Jewish Methods of Subverting It; Mosley and Anti-Semitism

Now at last came the end of the war, and with it a great outpouring of popular jubilation. The Chief Constable wrote to inform me that with the ending of the “State of Emergency” I was no longer required to report to the police.

Free for the first time since June 1940, I was almost in a celebratory mood, but though as a patriot I shared much of the general feeling, also as a patriot and I believe, a realist, I knew that it was largely a pyrrhic victory.

We had certainly brought about the defeat of Nazi Germany, but in so doing had reduced Britain to a near-bankrupted nation dependent on American aid, no longer able to hold the Empire together, and for ever after a third rank country.

What a paradox that a war which saw our “greatest hour” should prove to be our greatest undoing, and that a Prime Minister who stomped around growling about his resolute attachment to the greatness of Britain and the continuity of her Empire, should have been the chief instrument in the destruction of both!

And while this was taking place, the nations of Eastern Europe who the British politicians and Establishment had claimed to have fought a war to protect, were going over one by one to the slave masters of the Soviet Union.

All this had been foreseen by Oswald Mosley and British Union; loss of Empire, loss of British independence, and the rise to world dominance of the United States and the Soviet Union. One day an impartial historical judgement will re-assess the respective strategic policies of Churchill and Mosley, but at present, some 45 years after the end of that foolish, avoidable and disastrous war, the subject is still cocooned in a carefully preserved mythology, and protected – as the case of the British publishing and press boycott of David Irving’s Churchill’s War confirms, by an Establishment, all-party censorship.

Many of these thoughts occupied my mind as I watched the bunting go up over the streets. There was always the feeling that the war could have been avoided with dignity and honour, and millions of lives spared. It is almost impossible to describe this feeling to anyone who has not been in similar circumstances. It was as if conscience was at war with itself.

I had not wanted a German victory, and yet I could not experience any sense of satisfaction or joy at its defeat. It was a most unpleasant experience. I knew that I had to accommodate my thinking and indeed my whole life, to an unwanted situation, and I did not know how I was going to cope. I feel I was in some way a hypocrite, and to me hypocrisy is the vilest of all human wickedness.

By October 1945 the debating season was once again in full swing. I was invited to participate in a Brains Trust session one night, the subject of which was the Nuremberg Trials and related issues. These events were usually reported in the local press, and I hit the headlines as “John Charnley, member of the local Brains Trust claims to have known William Joyce.” This came about because I had attacked the principle of retrospective trials. Quite unblushingly, I gave it as my opinion that when Joyce entered Germany late in 1939, he did so from a genuine desire to halt the slide into war, and that for this he should not be condemned.

Shortly after I was asked if I would be willing to debate the Jewish question. I agreed to do so and thereafter much time was spent on the wording of the motion, which finally emerged as “That anti-semitism can be justified.”

Southport has always had a fairly large Jewish community, and the press adverts for the debate caused quite a furore. Attempts were made to get the debate stopped. Then the proprietors of the restaurant where it was scheduled to take place were asked to cancel the engagement, but this would have been in breach of a long-term contract. Then approaches were made to compel the police to get the debate banned, but under existing legislation they had no power to do so.

A few days before the debate the police arrived at my work, to tell me they would be in attendance and that I should be wary in my handling of the proceedings. Came the night of the debate, and the room was packed, with people standing at the rear. At the front were many Jews, who had been queuing well in advance of the meeting.

My opponent was a well-known local Jew whose name escapes me. He had a reputation as a good speaker. Opening the debate, I was aware I would need to temper my usual aggressive style if I was to succeed in getting a hearing. Sensing a subdued apprehension as I rose, I began by seeking to gain the audience’s sympathy stressing the need for an understanding of the cause of anti-Jewish feeling in numerous countries and over many centuries. I suggested that the constant repetition of persecutions such as that carried out in the reign of Henry VII must in itself denote some Jewish blame. To my pleasant surprise I was given a fair hearing, but there was little applause as I resumed my seat.

My opponent was more vitriolic in style, thereby giving me some grudging sympathy. He did, however, turn some of my arguments against me by suggesting that subconscious behaviour on the one part would not spark off violent opposition on the other, unless there was an inhibited desire for such a reaction. When the debate was thrown open I was surprised by the measure of support I received, giving me in the end, one third of the votes. The debate was well reported not only in the Southport press but in the Liverpool newspapers as well.

Anti-semitism of course, is a subject that figures prominently in any analysis of the Mosley Movement. In my numerous conversations with O. M. the Jewish question was never once discussed. As a matter of strict record, it was not until the Albert Hall speech of April 1934 – some 18 months after the founding of British Union – that Mosley first mentioned the Jews in a public speech, and this was to note that Jews were heavily conspicuous among those convicted by the courts for violence against individual Blackshirts, and disruptive and violent behaviour at Blackshirt meetings. Mosley also drew the attention of his audience to the growing Jewish campaign against Germany, and the danger this held for dragging Britain into a war. “We fought Germany once before in a British quarrel, we shall not fight her a second time in a Jewish quarrel,” he told the thousand who packed the Hall that night. Fair enough.

It cannot be denied however that numbers of Mosley’s supporters were anti-Jewish, some more blatantly than others. It was my own experience that openly expressed anti-semitism was far more evident in those areas where Jews constituted a large gathering in a restricted area.

Mosley’s condemnation of Jewish anti-Blackshirt violence and his attack on Jewish financial interests in the City of London unquestionably led to open expression of anti-Jewish hostility from many speakers. I must include myself in their number, though I always endeavoured to preface my remarks with a condemnation of specific behaviour by a section of the Jewish community.

When I paid my first visit to the Blackshirt headquarters in Southport in 1933, I sought and was given assurances that the Mosley Movement was not anti-semitic. Yet there is no disputing that in the hectic years that followed, my own attitude underwent a change. No doubt personal experience had much to do with it, as well as my endorsement of Mosley’s denunciation of finance and the Jewish mobilisation of anti-German policies and attitudes.

I was beaten up by a Jewish mob in Bury New Road and thrown through a shop window. Nine months later I moved to Hull, where intense political activity brought me into contact with members of the local Communist Party, many of whom were Jews. It is of interest to note in passing, that in his recent autobiography, the journalist and newspaper personality Derek Jameson said that nearly all the Communists in East London in the early postwar years were Jewish. I was involved in a number of scuffles with Jewish Communists over the years, and all encouraged the development of anti-Jewish sentiments which found expression at the many meetings I addressed. I heard Mosley address many hundreds of meetings however, and not once did I hear him utter any statement that could be described as anti-semitic, although on numerous occasions he attacked with the full force of his rhetorical powers, Jewish money power (pp. 178-183).

Moseley and Immigration; “Electoral Irregularities”

Travelling the country a great deal, I knew that the vast majority of British people were opposed to the creation of a multi-racial society. Union Movement had opposed coloured immigration since 1952. As Jeffrey Hamm, general secretary of the Movement in the late ‘50s and ‘60s, and now secretary of Action Society succinctly puts it, “We said it all and we said it first.”

The Movement’s far-sighted and always principled policy on immigration was denounced by the old parties and their media as “race hatred.” Others did indeed peddle hatred, but Mosley and Union Movement never attacked the immigrant, but rather those in authority in this country who ruined the Caribbean economies and then brought West Indians over here in large and increasing numbers to our northern island.

Mosley stood as Union Movement Parliamentary candidate for North Kensington – which included the Notting Hill area – in the General Election of October 1959. I went along to his adoption meeting which was wildly enthusiastic. I remember there were quite a number of coloured people present, and they were also wildly enthusiastic, no doubt because for the first time they were hearing an English politician talking about giving black people a square deal – in their own countries. There was absolutely no racial antagonism at this meeting, a point worth stressing in view of the slanders of our opponents.

In contrast to many Union Movement members and supporters, I didn’t expect Mosley to win, but his recorded vote of just under 3,000 was a shock to us all and the greatest disappointment of my life.

Mosley and the Movement had fought a magnificent campaign amid every sign of great popularity and enthusiasm. If even a large proportion of voting pledges had been adhered to, we would have won the day. There were electoral irregularities, including missing ballot boxes, but nothing could be changed.

Despite this disappointment however, Union Movement reached its greatest vigour and strength in the early sixties, until organised violence by Communists and Jewish elements at open air meetings in the summer of 1962 – accompanied needless to say by a thoroughly dishonest Press coverage and the old enmity of the Establishment – put a brake on the activities of a Movement led by a man in his 66th year.

But as with the lost peace of 1939/40 we can say, what a national disaster, what miseries and tragic errors would have been avoided if the sane, rational and humane immigration policies of Mosley and Union Movement had been implemented in the 1950s! (pp. 221-223).

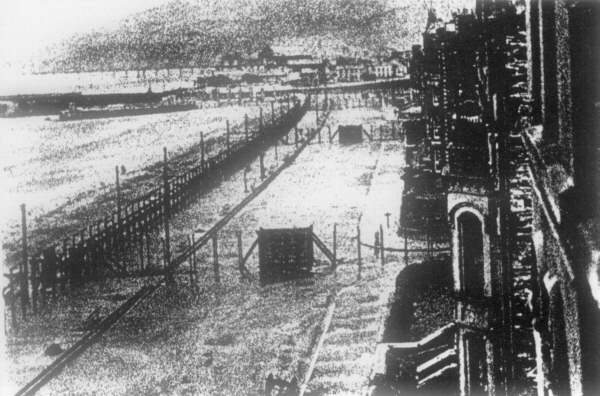

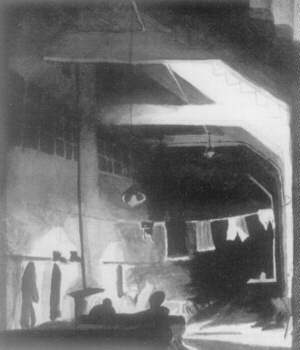

| The camp erected under the stands of York racecourse, seen here in a waterclour painted by detainee Rafe Temple Cotton, British Union’s Devon District Inspector and Parliamentary Candidate for Exeter, in 1941. |

|

The ‘Great Smother’

Am I still proud of my association with Oswald Mosley and his Movement? To this I reply that the days when I marched through the towns and cities of this land in the company of Mosley and his Blackshirts were the proudest of my life.

His politics attracted many bitterly disillusioned ex-service men and women, and thousands more disenchanted young men and women. Mosley was in a hurry. Why? Because he wanted to rebuild Britain, and above all avoid another war.

He failed because he ran out of time, and because he was deliberately denied press and radio. This ‘Great Smother’ operated from 1934 on. His opponents knew only too well that when the people heard Mosley, the people began to think, and in the main found themselves in agreement with his analysis and solutions. Former Labour Cabinet Minister, R. H. S. Crossman wrote (New Statesman, 27 October 1961):

“Mosley was spurned by Whitehall, Fleet Street, and every party leader at Westminster, simply and solely because he was right.”

Blackshirts and Roses, Brockingday Publications, London, 1990