|

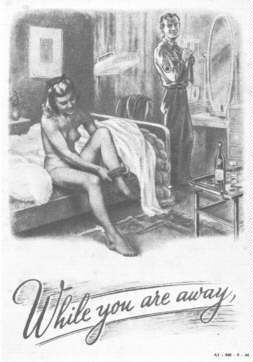

Love, Sex and WarJohn CostelloFrom Chapter 7: Jagged Glass

|

The reward for complicity in mass murder: Ham and eggs

The sheer size and technical sophistication of the World War II armies was such that two thirds of all troops were in support roles and were consequently never exposed to enemy fire at the front...

Just how this pent-up guilt contributed to what was called ‘combat stress’ was not to be fully appreciated until extensive wartime research revealed ‘battle fatigue’ to be one of the critical factors in cases of mental breakdown. The startling discovery was then made that only one American soldier in six could be consistently relied on to open fire on the enemy whatever the provocation. ‘Fear of killing, rather than fear of being killed, was the most common cause of battle fatigue in the individual, and the fear of failure ran a close second,’ was the conclusion of Brigadier General S. L. A. Marshall. Men Under Fire was based on the analysis of his interviews of combat veterans and the study of thousands of US Army action reports:

The Army cannot remake [Western man]... It must reckon with the fact that he comes from a civilization in which aggression, connected with the taking of life, is prohibited and unacceptable. The teaching and ideals of that civilization are against killing, against taking advantage. The fear of aggression has been expressed to him so strongly and absorbed by him so deeply and pervadingly – practically with his mother’s milk – that it is a part of the normal man’s emotional make-up. This is his greatest handicap when he enters combat. It stays his trigger-finger though he is hardly conscious that it is a restraint in him.

‘I remember myself as potentially expendable according to the Rules of Land Warfare, trapped in a war which (I said) was none of my making,’ was how one GI rationalized this conflict. Many soldiers steeled themselves emotionally before combat with the thought of home and the wife or sweetheart in whose memory, or offspring, they would have some hope of immortality if their own flesh was shattered by high explosive.

Most soldiers were unwilling or unable to contain their sexual starvation with thoughts of the women back home that they might not survive to embrace. ‘In the war a man gets lonely, a kind of loneliness which nothing can drive away except women – real ones and ones you can dream about waiting for you back home,’ a GI wrote to his father. ‘And it doesn’t matter much if they aren’t there when you come back. The important thing is to have this dream when you’re lying in a dirty ditch with bullets whistling all about you.’

That living with the prospect of death generated a high sex drive in the men most frequently in action was evident from the high VD rates suffered by Allied bomber crews. Unlike the infantryman, who had few channels for sexual release at the battlefront, aircrews had plenty of women around their bases. Lieutenant Ted Binder, one of the 9937 American airmen who perished in the great Allied bomber offensives over Germany, discovered when his turn came as mail censor just how promiscuous aircrews were. He was shocked at their boasts in letters to their pals of sexual adventures with English girls, while their letters to their wives or sweethearts back in the States contained assurances that they were their only loves.

I have found fifty sets of letters of this nature: one is to the wife or steady girlfriend back home. English girls, Joe says, are a mighty poor substitute for females. But of course even if they were Hollywood glamour girls, he wouldn’t be interested, ‘cause he can’t think of anything but his little Mabel back home. Letter No. 2 is to some girl Joe has met in England, who may or may not know of his previous connections, and who may herself have a husband in the 8th Army. ‘Darling,’ says Joe, ‘I never knew what life was till I met you. I live for those hours we have together on my leaves. You’re the luckiest thing that ever happened to me.’ And the third letter Joe put in the mail box that night is to his buddy working at Willow Run. ‘Pete,’ he says with enthusiasm, ‘you don’t know what you’re missing. These English broads really go crazy when they see a Yank. I’ve got a really nice little date lined up, and believe it or not, it’s all free.’

‘You went to war for six hours,’ was the way one RAF bomb aimer explained it, ‘and you came back to clean sheets and when you did an operation you got ham and eggs. Nobody else did.’ (pp. 135-137)

But I’m only a child

In the aftermath of the Russian troops’ entry into Vienna in April 1945 it was said that not even the female dogs were safe from sexual assault. The once-mighty Nazi propaganda machine summoned its dying gasps to use the rape of the Austrian capital to galvanize the Volksturm citizen militia into desperate resistance.

Ruined Berlin was peopled largely by old men and women who were unable to resist the medieval ferocity unleashed upon them by Red Army troops. Passions fired by the heat of victory, vengeance, and vodka paid no heed to the screams of terrified girls, ‘Aber ich bin noch ein Kind,’ ‘But I’m only a child.’ (p. 141)

What ZOG means by ‘liberation’

Many cases of the rape of French womenfolk were confirmed by Allied military investigations. On it September 1944, shortly after the Allied armies had crossed the Marne, a forty-three-year-old dressmaker called Maria Guerre lodged a deposition at local headquarters describing how she had been brutally raped in front of her husband and family by three GIs:

Yesterday, the 10th instant, towards 8:00 p.m. in the evening, my ten-year-old son, Gui, came home, bringing with him three American negro soldiers. After drinking a bottle of champagne these soldiers would not leave the house. At a given moment, during which my husband and children were restrained by one of these soldiers, the two others flung themselves on me and took off my knickers and raped me. An infirmity of my left leg caused one of them to have difficulty in achieving this object, so he struck me all over, wherever he could. These soldiers raped me, one after the other, and repeated this three times in succession... During this whole incident, which took place in the bed in my kitchen, I saw my husband, who was guarded by a soldier who held a dagger above him.

American military authorities immediately took steps to locate the men responsible and prosecute them under the 93rd Article of War. A week later, at an identity parade of the 3263th Quartermaster Service Company, the woman’s husband picked out a private he identified as one of the three assailants. The unfortunate (sic) GI shot himself thirty minutes later, but his accomplices were never brought to trial.

SHAEF headquarters imposed censorship on French newspapers reporting a rash of rapes and assaults on small girls. (pp. 142-143)

Warriors of democracy (German soldiers would have been shot)

Those who observed the Allied troops in Germany at first hand knew that rape was not a sinister sexual plot by female Nazi saboteurs. ‘The behaviour of the troops, I regret to say, was nothing to brag about, particularly after they came upon cases of cognac and barrels of wine,’ was the chastening report of one US Army intelligence officer who witnessed the occupation of the German city of Krefeld. ‘There is a tendency among the naive or the malicious to think that only Russians loot and rape. After battle, soldiers of every country are pretty much the same, and the warriors of Democracy were no more virtuous than the troops of Communism were reported to be.’ (p. 144)

Women the same the world over?

Allied military planners who persuaded General Eisenhower to adopt this strict non-fraternization policy had neglected to take into account the sexual hunger of either their troops or German women. This became apparent after Cologne had fallen in mid-March with a disturbing report that was received from an officer of SHAEF headquarters intelligence staff who had been amazed to hear the shouts of , ‘Ve haf vaited fife years for you!’ across shattered streets still littered with the bodies of civilians killed during the fighting: ‘Girls put on their most seductive smiles... and the girls in the recently occupied territory don’t seem to make any bones about the fact that the lack of young men in Germany left them in a rather receptive mood.’

SHAEF tried to cool the ardour of this reception by issuing an edict that, ‘Such women can hardly be considered as the suitable mates for the defenders of democracy,’ a promulgation that was more suited to the defeated Nazi regime than sexual reality. (p. 145)

Tricked into fighting people just like yourself

‘Two things our soldiers can’t resist – kids and a glimpse of married family life,’ reported the New York Herald Tribune from Cologne in a piece about the ‘Sixty-five dollar question... the fine stipulated for enlisted men convicted of intimate association with enemy civilians.’ ‘The biological aspects of boy-meets-girl can be rigidly controlled. But the kids here look like the youngsters back home, and the old folks seem harmless and their houses are nice and clean and they appear to live about the same as we do.’

The magnitude of the sexual problems confronting an Allied army of occupation had been foreshadowed in Italy. The ‘liberation’ of Paris and Brussels brought another leap in VD rates, as sex-hungry Allied soldiers filled the already bulging purses of the madams who ran the maisons tolerées in those cities. On the other side of the world, General Douglas MacArthur’s army had driven the Japanese out of Manila in the spring of 1945 – only to lose the battle against venereal disease to an estimated eight thousand-strong prostitute army of ‘native females wandering through military encampments and intimately associating with military personnel.’

The introduction of the ‘wonder-drug’ penicillin a year earlier had removed another restraint on the sexual activities of the Allied troops who set out on the crusade to ‘liberate’ Europe. The rapid upward leap in the VD charts kept by every regiment indicated that even the most cautious of soldiers were tempted to abandon ‘the bright shield of continence’ now they knew that health and honour could be restored by the ‘magic bullets’ of penicillin. (pp. 146-147)

Black troops more likely to use a condom?

The all-Negro regiments, which made up sixteen per cent of the theatre strength, proved to be the most sexually active with ninety-six per cent of black troops admitting to intercourse, compared to eighty-two per cent of white soldiers. Consequently VD rates amongst black soldiers averaged five times the rate for white ones, and in some units infections were being contracted by every second man. ‘Just why the Negro has more sexual intercourse is a matter of speculation,’ noted the survey, but other statistics collected by the army during the war showed that black GIs admitted to earlier and more frequent sexual activity as adolescents. When overseas, most of these troops were in supply and quartermaster regiments behind the front lines – so they had more opportunity for sexual activity. Although black troops were more likely to use a condom and take prophylactic measures than whites (sixty-two per cent compared to forty-three per cent), their far higher VD rates, the report pointed out, was because ‘women to whom they have access are much more likely to be diseased on the average than the white enlisted male contact.’ (pp. 147-148)

Too thick or too thin?

The survey concluded that there was ‘no evidence that frequent VD talks or movies cut down the exposure of men to VD overseas.’ Not only did the troops repeatedly ignore advice by chaplains and medical officers to ‘keep it in your pants,’ but fewer than half of the respondents used sheaths or prophylactics because, as one soldier put it, ‘most GI rubbers are so damn thick you can’t enjoy yourself and another explained, ‘GI condoms are no good. Half of them bust anyway. Try one sometime.’ (p. 149)

‘Sex life which society taught him was his’

The US Army sex-survey of 1945 that provided such a frank and decayed insight into the sexual impact of World War II on American troops was to be kept a classified secret for nearly forty years, because it reflected on the public image of the GI as a clean-living crusader for democracy. While no such detailed research into military sexual habits appears to have been conducted by British forces, their very similar VD statistics suggest that soldiers in both armies shared the same sexual habits.

The most revealing aspect of the US Army sex-survey was that it exploded once and for all the traditional belief that if a man knows a girl is waiting for him somewhere he will be true to her; he will not seek outlets with other women. ‘When it is an activity which is approved of by the group as a whole, not only by a man for himself but for the other fellow too, this powerful social sanction makes the activity almost uncontrollable.’ The American survey concluded with an observation that was appropriate to the sex lives of all soldiers in all the armies who fought in World War II:

However, the man in this study is not having an unusual amount of intercourse at all for men of his average age (twenty-six years). Any man of age twenty-six, and certainly any married man in the theatre (thirty-two per cent) can rightfully feel that he is being cheated sexually by this overseas situation which is not of his making. The steady rise in the frequency of intercourse with time overseas gives credence to this notion of being cheated of the sex life which society taught him was his as soon as he became a man. Furthermore, only ten per cent of all those men are having intercourse at least once a week, which is certainly not an indication of anything like abnormal sexual activity. The average frequency of once to twice a month is certainly not high, if we hazard guesses as to the probable frequency of intercourse for this group if they were in normal civilian life... the Army would make a mistake in either charging these men with sexual abnormality or threatening them as such. (pp. 150-151)

John Costello, Love Sex and War: Changing Values, 1939-45. William Collins, London, 1985.