|

Love, Sex and WarJohn CostelloFrom Chapter 12: Black Propaganda and Sexpionage

|

The Salon Kitty

EVER SINCE RAHAB THE HARLOT harboured Joshua’s spies before the capture of Jericho, sex has often played a part in clandestine intelligence operations as a means of extracting, concealing, or disseminating intelligence. World War I produced the legendary femme fatale Mata Hari, whose H-21 German code-designation was to expose her in 1917 after French counter-intelligence deciphered a cable to Berlin. Less notorious – because she was never caught – was ‘Fraulein Doktor.’ Dr Annamarie Lesser exploited her powerful sensuality to ensnare high-ranking French officers and stay one jump ahead of discovery while she spun a web of German espionage in wartime Paris that cost France one of her key fortresses.

It was not only spies who used sex in the cause of military and political advantage in World War I. British and French propaganda posters and cartoons luridly dramatized the so-called German rape of Belgium in a way that helped inflame American opinion against the Kaiser’s soldiers, who were represented as raping murderers.

Twenty-one years later, the Nazi’s regime had transformed propaganda into a sinister art. Dr Joseph Goebbels was able to exploit sexual and racial themes in broadcasts, films, and posters. For an outwardly puritanical regime which banned prostitution, abortion, and contraceptives and banished homosexuals to concentration camps, the German leaders had no private reservations about employing sexual themes in propaganda or using sex as both a weapon and bait in clandestine intelligence-gathering operations.

Although brothels were officially outlawed by the Third Reich, the elite Nazi SS security police had been authorized by Himmler before the war to engage prostitutes in intelligence gathering. The infamous Salon Kitty in Berlin’s Giebachstrasse was the brainchild of the Deputy Reichsfuhrer SS, Reinhard Heydrich. The high-class brothel was set up to increase surveillance of foreign diplomats and visitors as well as to gather dossiers on the sexual indiscretions of Nazi party big-wigs and government guests.

Hand-picked girls were specially schooled in the arts of seduction to pry confidential information – as well as high fees – from their clients. Cameras were concealed in hollow walls and the luxuriously ornate bedheads were bugged with microphones that were cunningly placed to convey the most intimate of amorous whispers to the battery of listening posts and recording machines set up in the basement. But Salon Kitty proved an expensive investment whose ‘sexpionage’ value never lived up to Heydrich’s expectations. Its recordings provided a great deal of bawdy entertainment for the SS listeners in the cellar but few significant political or diplomatic indiscretions were picked up by the time the outbreak of war reduced its usefulness. (pp. 241-242)

Black propaganda: Sefton Delmer plays ‘Der Chef’

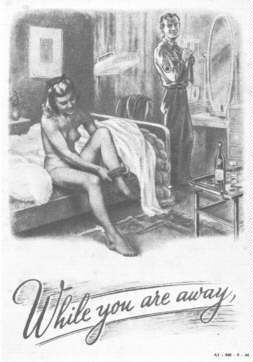

If the Axis efforts at using seductive female broadcasters to undermine the morale of Allied servicemen backfired completely, post-war evidence was to show that the intensive British and American efforts to turn sexually loaded propaganda against the enemy met with no greater success.

Britain’s ‘black propaganda’ was sponsored by the Government’s Political Warfare Executive, which had been set up to counter Dr Goebbels’ skilfully directed radio offensives. Stations were set up which purported to be broadcasting secretly from inside the Reich, run by various anti-Hitler groups. The German authorities’ sophisticated direction-finders quickly identified them as an enemy propaganda operation and announced severe penalties for anyone caught listening to these unauthorized broadcasts. To attract an audience British stations often included salacious or pornographic material – a favourite theme was to broadcast the intimate details of the sexual eccentricities of Nazi officials or Hitler Youth Leaders.

The mastermind behind Britain’s black sexual propaganda was Sefton Delmer, an Austrian expatriate who invented and played with great relish a tough Prussian character known as ‘Der Chef.’ Night after night he took to the airwaves to condemn the depravity and corruption of the Nazis. His scripts, a potent brew of patriotism and pornography, apparently attracted quite a following in Germany and Station GS-1, which was his identifying call-sign, was condemned by the German High Command for its ‘quite unusually wicked hate propaganda.’

Nor were the Germans the only ones to complain about the diet of sex and sadism with which Der Chef was spicing up his reports of the Reich’s administrative corruption and military bungling. A lurid account of an orgy broadcast by GS-1 in the summer of 1942, which supposedly related the graphic sexual acrobatics of a Kriegsmarine admiral, elicited a strong Foreign Office protest after the transmission had been picked up in Moscow. Sir Stafford Cripps, the austere British Ambassador to Russia, raised a bureaucratic storm about the propriety of such broadcasts. Delmer’s chief submitted a retort that drew an interesting parallel about the way that the undercover war was being fought:

If the Secret Service were to be too squeamish, the Secret Service could not operate. We all know that women are used by them for purposes which we would not like our women to be used, but we say nothing. Has any protest ever been made? This is a war with the gloves off, and when I was asked to deal with black propaganda I did not try to restrain my people more than M. (the Head of the Secret Service) would restrain his, because if you are told to fight you just fight all out. I am not conscious that it has depraved me. I dislike the baser sides of human life as much as Sir Stafford Cripps does, but in this case moral indignation does not seem to be called for.

Delmer, who was described by his boss as ‘a rare artist,’ was instructed to tone down the pornographic element of Der Chef’s scripts, but was otherwise encouraged to continue his contribution to the black propaganda radio war with his gloves off. His artful exploitation of sexual themes was to find its way into the broadcasts made by the other ‘secret’ British wartime radio stations, such as the ‘Atlantiksender’ station, which beamed its transmissions to U-boat crews, and the various ‘Soldatensenders,’ which broadcast news and music to German troops in Europe. Actual news was peppered with items reporting the scandalous sexual behaviour of Nazi party bosses with the wives of absent Wehrmacht troops; or revealing that Wassermann tests had shown that a large quantity of blood in German army field hospitals was contaminated with syphilis; or announcing the births of children to the wives of U-boat men who had not been on home leave for a year. These stations offered, like Tokyo Rose, plenty of music and a clever concoction of personal information and names of actual people gleaned from captured German sailors, soldiers, and airmen that was intended to upset the morale of the men at the front. They were reinforced by thousands of leaflets like those dropped over the French U-boat bases in 1943. These emphasized the high casualty rates in a captioned picture strip that stressed the awful suffering caused to seamen’s widows and families in the fatherland.

Yet for all Delmer’s acknowledged genius at inventing credible sexually loaded propaganda – which was incorporated in the broadcasts made during the European campaign by Eisenhower’s SHAEF psychological warfare teams – post-war evidence suggests that such broadcasts had little impact on Germany. As a leading member of Britain’s wartime Political Warfare Executive put it: ‘I am very dubious whether black propaganda, despite its brilliance in radio work, had any marked effect on the course of the war. It had to be so entertaining that it probably maintained morale!’

What is not disputed is that all the wartime broadcasts and sexually explicit leaflets had by their very nature initiated changes in Western society’s definition of pornography. By exploiting sex as legitimate – and entertaining – content for propaganda, both the Allied and Axis powers may have unwittingly helped to initiate the shift in public attitude that permitted the explicit treatment of sex in post-war novels as well as the reinterpretation of the magazine publishing laws which made popular what came to be known as the ‘Playboy Philosophy.’ (pp. 244-247)

Anna Wolkov, Tyler Kent and other incredible characters

The efforts of Anna Wolkov to carve a career for herself as an amateur spy were to have more far-reaching consequences than she herself realized when, on 20 May 1940, Scotland Yard’s Special Branch officers came down the steps of the dingy Kensington basement from which she had sallied forth at night to stick up pro-German posters in the blackout. Her arrest and subsequent trial alongside a cypher-clerk of the American Embassy in London was to be MI5’s first big counter-intelligence coup of the war.

Anna Wolkov was a stocky Russian-born woman in her mid-thirties. She had cast herself in the role of self-styled aide-de-camp to Captain Archibald Maule Ramsay. This distinguished ex-Guards officer and World War I military hero had been a founder member of The Link, the Anglo-German fellowship organization which had promoted contacts with the Third Reich throughout the 1930s. When the outbreak of war forced its dissolution, he established the less flagrantly unpatriotic ‘Right Club’ which continued clandestinely to foster pro-German sympathies amongst its blue-chip establishment secret membership. It included leading aristocrats, bankers, and parliamentary figures who feared the ultimate communist takeover of the West if Britain failed to take advantage of Hitler’s repeated peace offers. The Right Club committee used as its clandestine meeting place the cramped quarters above Wolkov’s father’s ‘Russian Tea Room’ restaurant, which also happened to be conveniently located near Ramsay’s London house and South Kensington underground station.

Anna’s ambition to become an important agent was fired by a pre-war pilgrimage to Germany in 1938, when she had briefly met Hitler’s deputy, Rudolph Hess. Although she was never actively recruited as a German agent, she became an ardent Nazi ‘fifth-columnist’ and might have remained a misguided fanatic’s gadfly to the British security services had not the Russian emigré circle in London brought her into contact with a personable young staffer from the American Embassy called Tyler Kent, who showed her copies of Churchill’s top secret cables to President Roosevelt. Anna Wolkov realized that if she could get Kent’s collection of documents to Berlin it would establish her reputation as a successful agent. Unfortunately for the conspirators, their plans were uncovered by a team of MI5 agents.

Kent protested that he was an isolationist sympathizer who was merely doing his patriotic duty by collecting proof of Roosevelt’s unconstitutional efforts to involve America in the war, evidence that might be used to demolish President Roosevelt’s anticipated bid for re-election in 1940. But a select trial nonetheless convicted both him and Wolkov, and although it was assumed at the time that Wolkov’s amateur conspiracy was directed to benefit the Germans, post-war FBI documents and British sources indicated that the Soviet Union was the real éminence grise in the affair – and that Tyler Kent’s long-time affair with a NKVD girl in Moscow indicated his own recruitment as a Russian agent to monitor the traffic passing between London and Washington. In addition, Kent’s arrest on an espionage charge embarrassed one isolationist American Ambassador, Joseph P. Kennedy, who was suspected of clandestine approaches to Berlin.

Anna Wolkov was the amateur spy at the centre of a very tangled web of intrigue whose outcome was to have a profound influence on the course of World War II. The Wolkov Conspiracy was used to persuade the War Cabinet to pass the draconian Defense of the Realm regulation in May 1940.

‘That Hohenloe woman’ – or why one should never trust a (half) Jew

In the United States, official secrecy still protects the sexual machinations of an expatriate Hungarian woman of whom President Roosevelt noted in 1942, ‘this is the kind of scandal that calls for immediate and very drastic action.’ The Princess Stephanie von Hoherloe was a widow whose affair with Hitler’s former commanding officer in World War I, Captain Fritz Widemann, had taken her right into the highest Nazi circles. Wittily vivacious, but no stunning beauty, she was an assertive female whose clever charm and fervent devotion made her a favourite of the Fuehrer’s ‘court circle.’ Although half Jewish, she had been accorded by Himmler the rare distinction of ‘Honorary Aryan’ for the services she had rendered to the Third Reich. These included her flair for extracting funds and support for the Nazi cause from influential business and newspaper magnates, one of whom was the British press-baron, the late Lord Rothermere.

Princess Stephanie and her lover, the handsome, square-jawed Captain Widemann, became the toast of influential circles on either side of the Atlantic. He was one of the leading agents of the ‘Auslander Organization’ through which the Nazis channelled support from Germans and German sympathizers abroad. Hitler himself was to credit their public relations effort with smoothing the path for Germany s annexation of Austria and Czechoslovakia – services for which the Fuehrer’s ‘Nazi Princess’ was awarded Leopoldskron Castle near Salzburg, an extensive estate that had been owned by the celebrated Jewish theatrical producer Max Reinhardt.

In the years before the war broke out in Europe, the Princess shuttled between London, Paris, Berlin, Madrid, and Rome. With Fritz Widemann she crossed the Atlantic on the unofficial but highly publicized mission for which Hitler was to make her the personal gift of a diamond-studded swastika brooch. One of her coups as an international go-between with the Nazis was to have been instrumental in arranging the 1938 meeting in London between Widemann and British Foreign Minister Lord Halifax which encouraged Hitler to gamble with certainty that Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain would avoid a war over Czechoslovakia at the time of the Munich Crisis.

The Princess’s deft behind-the-scenes manoeuvres amongst the rich and politically influential on both sides of the Atlantic convinced many observers that she was ‘one of the most dangerous women in Europe.’ The week after the war broke out in September 1939, she was lunching at the Ritz Hotel in London when a group of titled ladies publicly branded her a spy and insisted that the maitre d’hôtel asked her to leave the restaurant. Princess Stephanie, with the cool defiance that was to distinguish her wartime intrigues, continued to eat. She also refused to leave England, and pressed on until December 1939 with an unsuccessful law suit against her former patron Lord Rothermere for non-payment of travel expenses on an assignment he had given her.

Meanwhile Fritz Widemann had already arrived in the United States to take up the post of German Consul General in San Francisco – from where he was ideally placed to put the case publicly for supporting Germany while masterminding clandestine operations of Nazi sympathizers on the west coast in their bid to keep America neutral. The arrival of a ‘Nazi Princess’ in California early in 1940 prompted a whirl of publicity and social engagements through which Stephanie von Hohenloe was able to generate sympathy and attention for Hitler’s ‘peace offensive.’

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover was convinced that the Princess and her diplomat lover were dangerous Nazi agents and ordered a twenty-four-hour tail on their movements. FBI agents arranged hidden microphones through which they eavesdropped on a meeting that took place at the Mark Hopkins Hotel on 26 November 1940, when Princess Stephanie von Hohenloe and Widemann discussed possible peace initiatives with Sir William Wiseman, a banker who had been involved in British intelligence operations in America during World War I. Whether Wiseman was actually at the meeting with the official authorization of Sir William (Intrepid) Stephenson, then head of British Security Co-ordination in America, now appears highly unlikely in the light of recently declassified FBI and US Army intelligence files. They indicate that he was then already under suspicion as a pro-German who was busily trying to further Hitler’s peace offensive by soliciting American business pressure to force Britain to open negotiations with Berlin.

FBI telephone taps also revealed that the Princess was trying to get Wiseman’s help to avoid deportation by getting her visa extended through Stephenson’s British Security Co-ordination line to the British Government: and that Widemann was passing on to Berlin information being provided by a high-level sympathizer in the State Department. J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI Director, backed the moves to have the Princess deported, but she was to outmanoeuvre him by taking [as] her new lover the head of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, Major Lemuel Scholfield.

The arrest of Hitler’s Princess made headlines, but Schoefield personally squashed press speculation that a Hohenloe deportation was imminent by announcing on 20 May 1940 that proceedings had been dropped against her. ‘While in custody the Princess Stephanie has co-operated with the Department of Justice and has furnished information of interest,’ he told the press. ‘The Department believes her release from custody will not be adverse to the interests and the welfare of this country.’ Precisely what this important information was, Major Scholfield declined to reveal, but reporters noted that he was to be seen driving the glamorous princess around San Francisco, and sensed that a spy scandal was about to be uncovered. Columnist Drew Pearson dropped hints in The Washington Times-Herald that the Princess had won her freedom with ‘some amazing revelations about subversive operations in this country and Britain.’ Hoover, who wanted to deport both the Princess and her ex-lover Captain Widemann, could not get the Justice Department to deliver any of these revelations: all he was told was that ‘it was being typed up by Lemmy’ (Scholfield).

However, Widemann was forced to abandon his operations and pack his bags when all Axis consulates in the United States were closed in retaliation for Japan’s takeover of Indochina in July 1941. By this time Princess Stephanie had moved to Washington’s luxury Wardman Park Hotel, where her continuing affair with the chief of the Immigration and Naturalization Service threatened to become a national scandal as she hinted to reporters that she was about to publish a book containing the startling ‘secret information’ she had given Scholfield.

Finally, in August 1940, Acting Attorney General Francis Biddle instructed Scholfield to get his mistress out of town before she became a public embarrassment to the administration. The FBI was still being denied the information needed to arrest her when, using the alias ‘Nancy White,’ she managed to slip away to Pennsylvania. The press sleuths were soon to uncover what they called a ‘love nest,’ where the FBI was already keeping tabs on the comings and goings of her continuing passionate liaison with Scholfield.

On 8 December 1941, a matter of hours after Roosevelt made his formal declaration of war, Hoover acted on the new powers the FBI had been given by executive order to round up potential enemy spies. The Princess Stephanie von Hohenloe was unceremoniously bundled into an FBI limousine as she stepped out of a Philadelphia theatre, leaving her eighty-nine-year-old mother screaming on the pavement. At the Gloucester immigration station in New Jersey, she was put in solitary confinement. When Hoover finally discovered that the ‘confession’ Scholfield had announced had never existed, the sparks began to fly within the Justice Department. Even the Attorney General’s role in the affair came under suspicion after the Princess’s address book was found to contain his private office telephone number.

The report to Hoover made it very clear that she must have enjoyed the protection of someone high in the administration besides the Head of the Immigration Service as there was evidence of ‘a very influential friend in the State Department whose mistress she had been.’ Just who this mysterious protector was is still blanked out in the sanitized FBI reports. But his influence must have continued after her arrest since, threatened with expulsion from the country, the Princess feigned illness and, with the tacit assistance of her lover, resisted deportation from the Gloucester detention centre. The President himself took a hand in the affair.

He wrote to Attorney General Biddle on 11 July, ‘Unless the Immigration Service cleans up once and for all the favouritism shown to that Hohenloe woman, I will have to have an investigation made and the facts may not be very palatable, going all the way back to her first arrest and her intimacy with Scholfield...’

Biddle appears – with good reason – to have taken Roosevelt’s threat personally, since he decided to transfer the case as far away from Washington as possible. The Princess was dispatched to a Texas detention centre at Seagonville with her mother and Scholfield following with the baggage. While her mother established herself in a suite at a nearby Dallas hotel, the Princess renewed her offer to tell the FBI about her association with Fritz Widemann and the implications of her liaison with Major Scholfield – offering too, in desperation, to include personal information about Goebbels and Hitler if she could be guaranteed her freedom. ‘Princess H. is a very clever and, consequently, a very dangerous woman,’ noted the FBI memorandum to Hoover which advised, ‘she is manoeuvring now to play the Bureau against the Immigration Service so she will get something out of it.’

The Justice Department then closed ranks and nothing came of the Princess’s final machination, which was a last ditch letter to Hoover in which she sought to reveal ‘matters which I can only relate to the President.’ Roosevelt nonetheless personally overruled the board that recommended releasing the Princess from detention in March 1944. Despite a suicide attempt early in 1945 Princess Stephanie von Hohenloe was not set free unto just before V-E Day – when she went to live with Major Scholfield, who took her home to his Philadelphia farm.

The tough resilience which had been the cornerstone of an extraordinary career enabled the Princess to make a quick recovery from her long ordeal, and she even triumphed over the stigma that had attached to her during the war to make a comeback of sorts on the New York social scene. Fritz Widemann also secured immunity from prosecution at Nuremberg, having spent the remainder of the war in China after successfully claiming that he had been instrumental in saving Jews and giving encouragement to the plots against Hitler.

Elizabeth Amy Pack (nee Thorpe) and the Enigma codes

A diplomatic wife turned British spy whose cool cunning and audacity made Mata Hari look like a novice became one of the most successful female undercover agents of the war. She was Elizabeth Amy Thorpe, who was born in Minneapolis in 1910. The precocious daughter of a captain of marines, Elizabeth was seduced at fourteen when she fell into a tempestuous affair with ‘an old gentleman of twenty-one.’ After completing her education in Switzerland and a smart Massachusetts ladies’ college, she became an aggressive socialite. Her success was guaranteed by her striking beauty that was crowned by fine auburn hair and eyes ‘like a dash of green chartreuse in a pool of limpid brandy,’ according to one of her admirers. At the age of twenty-one and pregnant, she married Arthur Pack, a second secretary at the British Embassy. Twenty years her senior, Pack had attracted her because his maturity contrasted with the American youths of her own age.

Friends were astonished at the odd match, because Pack’s pomposity was combined with physical ill-health caused by old war wounds from 1918. Marriage, however, in no way interfered with Mrs Elizabeth Pack’s continued promiscuous dalliances. She found no lack of opportunity for sexual adventures on the diplomatic circuit in Chile and then in Spain during the Civil War, where her remarkable powers of persuasion were employed in getting her Spanish aviator lover released from a Republican jail. And when Arthur Pack was posted to the British Embassy in Warsaw in the summer of 1937, she quickly became a sought-after companion for the young men of the Polish Foreign Office.

A trivial piece of intelligence gleaned during one of these liaisons started the diplomat’s wife on her long and successful career as a spy. After being put on the payroll as a part-time spy for British intelligence, Elizabeth Pack soon discovered that the game of espionage added a certain spice to amorous adventures, especially when she was told to strike up a relationship with the confidential aide of Colonel Josef Beck, the Polish Foreign Minister. ‘I would have made a dead set at him, even if he had been as ugly as Satan. But happily this wasn’t necessary,’ she later confessed. Through her affair with him Elizabeth Pack picked up vital clues that led to the unravelling of the German ‘Enigma’ codes which were to play such a crucial role in the Allies’ wartime intelligence effort. Accompanying Beck’s aide on his official missions to Prague and Berlin, she was able to obtain information that confirmed the extent to which the Polish Secret Service had successfully penetrated the Wehrmacht’s top-secret cypher system.

After her first mission was completed, the Packs were posted back to Chile, where Elizabeth made a name for herself as a freelance journalist with a Santiago newspaper. When war broke out she took it as a cue to desert her ailing husband and moved back to the United States where she worked as a reporter under her maiden name of Elizabeth Thorpe.

Summoned to New York by William (Intrepid) Stephenson, she was recruited as a full-time agent under his control with the code-name ‘Cynthia.’ In the winter of 1940-1 Stephenson’s BSC undercover intelligence operation arranged for her to rent a two-storey house in Washington’s select Georgetown district, as a base for her mission of obtaining the Italian naval ciphers. The target she selected for her sexual advances was Admiral Alberto Lais, with whom she was already acquainted and who was therefore no stranger to her persuasive charms. It was not long before the beautiful woman with the green eyes, who claimed she was working for American naval intelligence, had talked him into providing code books, which within a matter of weeks played a part in bringing about the defeat of the Italian battlefleet off Cape Matapan on 28 March 1941.

Lais had also told Cynthia of an Axis plan to sabotage British ships in American ports, so it became easy for Stephenson to effect his removal from the scene by passing the information to the FBI that his diplomatic status was compromised. Then, in May, Stephenson personally briefed Cynthia for her next task: to obtain all the Vichy French cypher systems and code books.

Starting out in New York’s Pierre Hotel, which was a favourite of the wartime Vichy diplomats, Cynthia used her cover as a journalist to target the French Embassy’s press officer for her initial assault. Captain Charles Brousse, a former fighter pilot with the French Navy, was an officer who took his duty seriously. But he had no special love for the Germans, as Cynthia discovered when he sat in on the interview which she had astutely arranged with his Ambassador for an article on current Vichy policy towards Britain and the United States.

A bouquet of red roses together with a luncheon invitation which arrived next day initiated a passionate affair, and for two months they managed to carry on the liaison under the nose of Brousse’s wife. Cynthia and Stephenson anticipated that they would soon have the code books in British hands. Then Brousse announced he would have to accept half pay or be posted back to France as a result of economy measures by the Vichy Government. He asked Cynthia to go to France with him, but she and Stephenson hatched a scheme in which she was to offer to make up his salary by pretending to be working for the still-neutral American Government, who she said would pay handsomely for copies of cables and ciphers.

Brousse, as Cynthia had confidently predicted, fell in with the scheme and soon a regular flow of embassy reports, intelligence traffic and files were passing through the BSC headquarters in New York. Cynthia then moved into the Wardman Park Hotel, where Brousse and his wife were living, to facilitate their contacts and avoid the attention of the FBI, which was becoming concerned at the extent of the BSC undercover operations. Valuable though the information that Brousse provided was, he still could not get his hands on the naval cypher books and codes that the British Admiralty was pressing for. Cynthia managed then to seduce the French Naval Attaché, but failed to persuade him to betray his navy’s secrets. His complaints to the Ambassador about her activities were skilfully countered by Brousse’s denunciation of his colleague’s other scandalous affairs.

In a new scheme to get the naval cypher books out of the safe in the guarded code-room, Brousse began working late at the embassy – while Cynthia was instructed by BSC’s lock-picking experts. After two attempts to open the safe failed, they decided to call in a professional Canadian safe-cracker. Brousse managed to get him into the embassy once the lone security guard had been encouraged to beat a discreet retreat after opening the door to see Cynthia and Brousse entwined naked on the floor making love. This time the crucial code books were extracted and passed out of Brousse’s office window to be photographed and returned to the safe. The operation succeeded without a hitch, and possession of the Vichy naval cyphers enabled the Anglo-American forces involved in the North African landings in November 1942 to be certain that the French naval units in the Mediterranean did not make any hostile move towards the Algerian invasion beaches.

After these landings the United States ended its neutrality with the Vichy regime and Brousse was interned with the rest of the Embassy staff. Cynthia was posted to the Special Operations Executive in London, but was never given another operational mission. After the war, with news of her husband’s suicide, Cynthia married Brousse, who had obtained a divorce from his wife.

The intelligent exploitation of Cynthia’s sexual charm and capacity for adventure had certainly rewarded British intelligence with information that directly helped to speed the course of ultimate Allied victory. Indirectly, she provided cover for the much more important ‘Ultra’ operation, because information about the break-in at the Vichy Embassy was later to be leaked to Berlin to allay German suspicions that their top-secret code ‘Enigma’ cypher traffic was being read. (pp. 248-258)

Anthony Blunt, Kim Philby, Guy Burgess et al.

The American and German male brothel operations represented a crude attempt to exploit homosexuality to obtain information about shipping, but Soviet intelligence was able to tap the highest Allied councils with a far more sophisticated operation which used the secretiveness of an elite homosexual network to burrow moles into the British and American bureaucracies. This far-reaching intelligence strategy, whose full ramifications were not to become apparent for another quarter century, had commenced shortly after World War I when candidates willing to serve the long-term cause of communism were recruited from the academically gifted sons of the British ruling establishment, studying at Cambridge and Oxford.

These converts to communism, such as the scholarly art historian Anthony Blunt and the wildly promiscuous Guy Burgess, who combined precocious intellects with homosexual inclinations, were suited for the task of burrowing into the British establishment. They were aided by university colleagues like Donald Maclean and Kim Philby, who were not committed homosexuals but were no less dedicated to the Marxist cause. The political delusion of the 1930s was that the rise of Fascism and Nazism appeared to force democratic societies into making a choice between the extreme right and the extreme left. With the encouragement of their Russian control officers, this secret fraternity of politically ‘enlightened’ young high-flyers kept in touch and furthered each others’ careers as they set out to scale the academic and bureaucratic fabric of Britain’s ‘Establishment,’ awaiting the call from Moscow when they were in positions of trust and influence.

The Soviet penetration strategy worked so well that by 1941, when Stalin needed to marshal Russia’s military production and diplomatic sinews to stave off the German military onslaught in World War II, the Kremlin could rely on a high-level intelligence network that accurately monitored the policy-making decisions of Britain’s Foreign Office, the deliberations of the State Department, and the White House itself. Moscow had tapped the ‘Ultra’ secret from Britain’s tightly guarded Bletchley Park code-breaking facility; had monitored the development of the atomic bomb through agents working on the Manhattan project; and, perhaps most seriously, had penetrated MI5 and MI6, the British military intelligence agencies. This astonishing success of Blunt, Philby, and Burgess – and perhaps other ‘sleepers’ – was achieved not by hiring Mata Haris or sending spies on cloak-and-dagger missions, but by the skilful manipulation of a dedicated network of traitors.

One of the most insidious and successful of these wartime moles was Professor Anthony Blunt, the art historian and ‘managing director’ of the Cambridge homosexual spies, many of whom he had personally recruited. In 1938 he volunteered his services to the War Office and was posted to the training school for intelligence officers a year later. When it was noticed that he had visited the Soviet Union in 1935, he was easily able to allay suspicions about left-wing sympathies by pointing to his impeccable connections: as a second cousin of the Queen-Mother, and with his advice on paintings sought and valued by the highest in the kingdom, it was impossible to believe that Blunt was a security risk.

After an ill-fated spell with the Field Security Police in France, which almost led to his capture in the German advance on Dunkirk, Major Blunt was posted briefly to MI5’s security division. At the instruction of his Soviet controller, ‘Henry,’ he applied for a transfer as personal assistant to the director of the counter-espionage division. His fellow communist conspirators were already rising in Britain’s wartime intelligence. Philby was with MI6 counter-intelligence and a place had been found in SOE for Burgess, his chief wartime collaborator, who acted as a link with a Swiss diplomatic informant.

For most of the war Blunt remained in charge of one of the most sensitive of all MI5’s operations – the interception of the diplomatic bags of the neutral embassies in London. The pouches were intercepted and collected under Blunt’s supervision then carefully slit open: their documents were copied and the stitches reinserted and dyed to match the worn side before the pouches were sent on their way. Blunt, on his own admission, must therefore have passed a great deal of extremely valuable information to Moscow that would have facilitated Stalin’s strategy in taking over eastern Europe and making a grab at the Balkans. But Major Blunt’s most infamous hour came in the spring and autumn of 1944, when he was transferred to General Eisenhower’s SHAEF headquarters to liaise with military intelligence. His involvement with the D-Day deception plans meant that Stalin was almost certainly informed well in advance of the secret that Roosevelt and Churchill were at great pains to keep from the Soviet leader – the time and place of the Normandy invasion. Stalin must have decided that it was not in Russia’s military interests to inform Berlin of the vital secret which could have turned D-Day into the Allies’ biggest defeat of the war. He needed the opening of the Second Front to draw off German reserves and accelerate the Red Army’s advance westwards.

Blunt and his coterie of fellow conspirators were able to feed the Soviets with vital items of military intelligence. They also provided Moscow, throughout the war, with an invaluable stream of political background and policy decisions tapped from the circles in which they moved. If the Germans were the immediate losers in the war of sexpionage and sexually loaded propaganda which Hitler had launched into with such confidence, despite American and British triumphs, it was the Soviet Union which won the ultimate victory in this arcane form of total warfare. (pp. 260-263)

John Costello, Love Sex and War: Changing Values, 1939-45. William Collins, London, 1985.