|

Love, Sex and WarJohn CostelloFrom Chapter 13: The Girls They Left Behind

|

Fifteen and sixteen-year-old war brides. Allotment Annies

In the United States a rash of teenage girls married their high-school boyfriends as they were drafted. Thousands of young brides followed their new spouses to rural towns near army training camps. This put a severe strain on housing and medical facilities. ‘When the troops came, right on their trail would come the little war brides, fifteen and sixteen-year-old kids from every corner of the nation,’ recalled Dr Thomas J. Taylor, whose small mid-west practice was swamped by young mothers-to-be from the adjoining army transit camp. ‘They’d just be dumped off in our little town, and of course every one of them was pregnant and ready to deliver.’ Apart from the obstetric complications, the welfare problems which resulted were enormous:

I vividly recall when a second-class rooming house was jammed with war brides and babies and I was called there because of a rather severe flu epidemic. I remember walking through that rooming house and each room had three or four mothers with babies, all of them, and they all had the flu. A bathroom down the hall, no money, desperate. I tried to do right and called the Salvation Army. In that particular case they did a heroic job clearing up that mess. This was repeated over and over in staging areas throughout the country until finally, late in the war, the message got through to most of these kids and they didn’t follow their husbands out.

In addition to the social problems created by the migration of rootless teenage wives, there were the notorious ‘war-brides’ called ‘Allotment Annies’ who hustled departing soldiers into marriage to collect the twenty dollars a month the US Government automatically allotted to servicemen’s wives. With a private’s pay rising to fifty dollars a month for overseas service, some greedy ‘Annies’ took on four, five, and even six husbands. These unscrupulous women made bigamy a business, and in return for V-mail letters to GIs overseas they lived very well off the pale blue-green Government cheques. Some, with the financial acumen of actuaries, specialized in airmen, anticipating that their higher mortality rates would increase their chances of collecting the ten thousand dollar jackpot Government insurance cheque issued if their husband was killed in action.

Elvira Taylor achieved national notoriety as the ‘Allotment Annie’ who operated out of Norfolk Virginia and specialized in sailors. She managed to snare six live ones and was about to hook a seventh when she was arrested as a result of two of her ‘husbands’ starting a fight in an English pub when they showed each other her picture as their ‘wife.’ When they had been cooled off by the military police, they joined forces to expose the duplicitous Elvira, who was discovered by checking the navy pay records to have contracted four other bigamous marriages.

While ‘Allotment Annies’ took care not to become burdened with offspring, the twenty per cent leap in the American marriage rates resulted in a baby boom. A similar celebratory jump became apparent nine months after the navy’s tide-turning victory at the Battle of Midway in June 1942, and through to the end of the war the American birth rate continued to peak nine months after every Allied triumph – El Alamein, D-Day, and the fall of Berlin. This natal phenomenon appears to indicate that victory euphoria confirmed many couples’ hopes of a stable future.

In Britain, by contrast, the birth rate actually declined between 1939 and 1941 in spite of the record number of marriages recorded in the first two years of the war, doubtless an indication of parental apprehension about the nation’s chances of survival. The Allied victories in 1943 and 1944, however, appear to have been celebrated with the same procreative urge as in the United States, as births in those years were pushed up ten and twenty-five per cent over 1939 in anticipation of ultimate Allied victory – and the presence of a million American troops in England in the run-up to the long awaited invasion of France. (pp. 268-270)

Soldier jilted

An American girl who had been going steady with a soldier posted overseas in 1943 jilted him after receiving a letter from him telling of the emotional strain of life at the front:

He was sent to Italy where the fighting was very intense for a long time, and he wrote to me whenever he could. Then, in one of those V-mail letters, he told me he cried many nights during the heavy fighting. In my sheltered life with my stereotyped notions of what a man constituted, the thought of his crying turned my stomach. I was convinced I had loved a coward. I never wrote to him again. (p. 272)

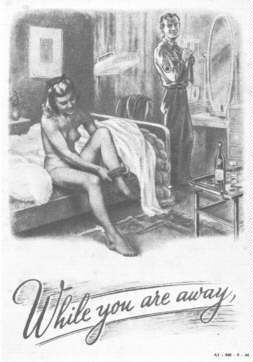

‘Dear John’ letters. Casualties back home

A GI stationed in Persia in 1943 received what GIs came to know as the ‘Dear John’ letter asking for a divorce:

The time has come to clear things between us. You will have realized before now, that our marriage was a mistake. I beg of you to put an end to this mistake and get a divorce. I left your house this morning, because I didn’t want to saddle you with the role of a betrayed husband. As a matter of fact, I have never been yours, but now I belong to someone else, and this finishes things between us... Elaine.

In anger and desperation, this particular soldier passed his wife’s brush-off letter to Yank magazine, asking if his faithless wife could still go on receiving his monthly allowance. He was advised to apply to a legal assistance officer for a divorce: ‘Yours is a classic version of a common problem. All the proof in the world that a soldierly wife is faithless does not change the fact that a family allowance is given to her regularly as long as she remains legally married to the soldier.’

Nor was it only the absent fathers who suffered as a result of their wives carrying on. One wartime child remembered how his playmate was affected:

His mother wasn’t a woman of high morals, if you know what I mean. She sort of slept around a lot while her husband was gone, and sometimes when she got the twitch in the middle of the day, she’d bring her boys home with her for a little tumble and send the kid over to see us. We knew when that was going on because he would always arrive crying, or, if he wasn’t crying, we’d see him hanging around in our backyard looking like he’d been kicked. (p. 273)

Female financial independence

That war jobs and long periods of separation gave many wartime wives a new sense of independence was indisputable. ‘The more money, the less family life, is an established pattern in the United States which war psychology has merely emphasized,’ wrote an American sociologist of the new mood of the sixteen million working women – six million of whom were married, worked, and continued to rear children under fourteen years of age. Fired by this new sense of financial independence, some women abandoned their husbands and families without even the formality of a divorce. (p. 274)

Wartime adultery and divorce

One out of every three American servicemen were married by the end of the war. There was a doubling of petitions for divorce by 1945 when, for every hundred couples getting married, thirty-one were legally separated. In Britain the comparable figures was five divorces for a hundred marriages, but this was up from the one in a hundred level of 1939.

Under US wartime law if a GI husband overseas refused to consent to proceedings, his wife often found it impossible to obtain a divorce as long as her husband was in uniform, because many American judges regarded it as their sacred duty to try to preserve the sanctity of the family while the war was on. After V-J Day this restraint was removed and the number of divorce petitions shot up.

The wartime divorce phenomenon afflicted British servicemen to the same increasing degree. The number of adultery petitions filed after 1942 rose by a hundred per cent each year above the 1939-42 average. The final twelve months of the war also saw a spectacular eightfold jump in the number of husbands who were suing for divorce on the grounds of adultery. By 1945, two out of every three petitions were being filed by men, whereas until 1940 female petitions had been in the majority.

‘Separation was intolerable for some wives and sweethearts,’ was one British wife’s rationalization of the epidemic of wartime adultery. According to her, the pressures that led many wives into extra-marital affairs were compounded because they even achieved a measure of social acceptability. (pp. 274-275)

Wartime illegitimacy

Of the 5.3 million British infants delivered between 1939 and 1945, over a third were illegitimate – and this wartime phenomenon was not confined to any one section of society. The babies that were born out of wedlock belonged to every age group of mother, concluded one social researcher:

Some were adolescent girls who had drifted away from homes which offered neither guidance nor warmth and security. Still others were women with husbands on war service, who had been unable to bear the loneliness of separation. There were decent and serious, superficial and flighty, irresponsible and incorrigible girls among them. There were some who had formed serious attachments and hoped to marry. There were others who had a single lapse, often under the influence of drink. There were, too, the ‘good-time girls’ who thrived on the presence of well-paid servicemen from overseas, and semi-prostitutes with little moral restraint. But for the war many of these girls, whatever their type, would never have had illegitimate children. (pp. 276-277)

Wartime abortions

Neither British nor American statistics, which indicate that wartime promiscuity reached its peak in the final stages of the war, take account of the number of irregularly conceived pregnancies that were terminated illegally. Abortionists appear to have been in great demand during the war. One official British estimate suggests that one in five of all pregnancies was ended in this way, and the equivalent rate for the United States indicates that the total number of abortions for the war years could well have been over a million.

These projections are at best merely a hypothetical barometer of World War II’s tremendous stimulus to extra-marital sexual activity. The highest recorded rate of illegitimate births was not among teenage girls, as might have been expected. Both British and American records indicate that women between twenty and thirty gave birth to nearly double the number of pre-war illegitimate children. Since it appears that the more mature women were the ones most encouraged by the relaxed morals of wartime to ‘enjoy’ themselves, it may be surmized that considerations of fidelity were no great restraint on the urge of the older married woman to participate in the general rise in wartime sexual promiscuity. (pp. 277-278)

Unmarried mothers

The wartime rise in illegitimacy rates put pressure on the public welfare authorities in Britain and the United States to assume the burden of a social problem which wartime conditions had greatly accelerated. Historically, the unmarried mother had been made an object of disgrace, to be pilloried in the market place or forced to stand at the Church door on Sundays shrouded in a while sheet. In World War II, however, the unmarried mother became a candidate for social welfare rather than a target for moral outrage. (p. 278)

Wartime delinquency and the ‘patriotutes’

The impact of World War II was to effect quite dramatic shifts in the behaviour and attitude of society. ‘Total war is the most catastrophic instigator of social change the world has ever seen, with the possible exception of violent revolution,’ was how a leading American sociologist put it. Francis E. Merrill, a professor at Dartmouth College, observed in his 1946 study how wartime duty had transformed the American nation into a ‘people doing new things – grimly, protestingly, gladly, semi-hysterically – but all changing the pattern of their lives to some extent under the vast impersonality of total war.’

Millions of families work out new adjustments, as the wife and mother plays the roles of the absent husband and father. Millions of women go to work for the first time in their lives, often at hard and exacting manual labour in shipyard and aircraft factories. Millions of their children somehow learn to fend for themselves and come home from school to an empty and motherless house. Millions of wives, sweethearts, mothers, and fathers are under constant nervous tension with their loved ones in active theatres of operations. Millions of wives learn to live without their husbands, mothers without their sons, children without their fathers, girls without their beaux.

The universal wartime disruption of family life would have its most profound effect on adolescents, who by the final years of World War II were creating a major juvenile delinquency problem in every warring nation. Arrests of teenagers were up, no matter whether it was Munich, Manchester or Milwaukee. The files of the German SD security police, British probation officers, and juvenile courts across the United States attest that juvenile sex delinquency was one of the most widespread social problems of the war.

Britain was the first nation to be afflicted with high wartime arrest rates for teenage girls. There was a one hundred per cent increase in the first three years after 1939 and large numbers of them were judged in ‘need of care and attention’ – indicating that they were morally ‘at risk.’ An East London magistrate stated that the ‘earlier maturity’ and the ‘jungle rhythms heard by juveniles from morning unto bedtime, and slushy movies are in part responsible for an increase in sex delinquency among youths.’ Other factors were the unsettling experience for city schoolchildren of the 1940 evacuation to the country, and the government’s mobilization of women, which included the mothers of adolescents aged fourteen years or more.

So many fathers were absent from home in military service that wartime adolescents were deprived of parental supervision and discipline at a critical stage in their emotional and sexual development. Girls could leave school at fourteen, and there were plenty of servicemen to provide excitement as an escape from wartime deprivations. By 1943, London and the other large cities were crowded with GIs, Canadians, and other foreign troops. In one London borough the number of teenage girls judged ‘in need of care and attention’ had multiplied sixfold in the year before the invasion of France. Americans had a special fascination for such girls, according to a probation officer from London’s dockland area:

All that seems to be necessary is for the girl to have a desire to please... Those girls who are misfits at home or at work, or who feel inferior for some reason or another, have been very easy victims. Their lives were brightened by the attention... and they found that they had an outlet which was not only a contrast, but was a definite compensation for the dullness, poverty, and, sometimes, unhappiness of their home life.

An emergency Home Office study commissioned that year left no doubt that the GIs were a major stimulus of this wave of sexual delinquency:

To girls brought up on the cinema, who copied the dress, hairstyles, and manners of Hollywood stars, the sudden influx of Americans, speaking like the films, who actually lived in the magic country and who had plenty of money, at once went to the girl’s heads. The American attitude to women, their proneness to spoil a girl, to build up, exaggerate, talk big, and to act with generosity and flamboyance, helped to make them the most attractive boyfriends. In addition, they ‘picked-up’ girls easily, and even a comparatively plain and unattractive girl stood a chance.

If it was the glamour of the GIs’ Hollywood image which aroused the erotic passions of British teenage girls, their counterparts across the Atlantic were stirred by a misguided adolescent patriotism. While their brothers participated in the national war fervour by joining up, thereby assuming the trappings of manhood, adolescent American girls had no such outlet. Psychologists surmized that the ‘Victory Girls’ or ‘cuddle bunnies,’ as they were called, saw ‘uniform-hunting’ at railway stations and bus terminals as their way of sharing in the wartime adventure. When detained by the police they would often claim that they were sexually promiscuous ‘Because it’s my patriotic duty to comfort the poor boys who may go overseas and get killed.’

An army flyer at a base-training camp in rural Illinois recalled that the adolescent prostitutes in the nearby town would ‘pick up guys at a soda fountain or in movie theatres and take them out in daddy’s car and go at it. Some of them took on four or five guys a night.’ Most of the young servicemen preyed upon by these girls were lonely and naturally not averse to accepting the sexual invitations they were offered. The ‘patriotutes’ as they were dubbed in the American press often dispensed their favours for a Coca-Cola, a meal, or the price of a movie. (pp. 279-281)

High-school good-time girls

‘Good-time girls of high-school age are the army’s biggest problem today as a potential source of disease’ announced a 1943 report from the base surgeon of large mid-western army airfield. The report concluded, ‘While mothers are winning the war in the factories, their daughters are losing it on the streets.’ Well over half of all the women arrested for sexual offences in the United States by the end of the war were under twenty-one. FBI statistics show that there had been a seventy per cent increase in teenage prostitutes, and in cities like San Diego, with a large transient service population, the number of girls arrested had increased threefold. According to US Army records, nearly half of the soldiers who contracted VD blamed girls under nineteen years of age. (p. 282)

John Costello, Love Sex and War: Changing Values, 1939-45. William Collins, London, 1985.