|

Claud Cockburn |

The Wonder Rabbi and Other Stories

|

|

Claud Cockburn, Sefton Delmer and the Wonder Rabbi

I had loved that neck of the east European woods too. Mr Sefton Delmer (who worked for the Daily Express) and his wife once – about Munich time – drove me down there from Prague, and we saw a man like Moses tending calves. One of the calves leaped a ditch and got itself struck by the car. It looked poorly, but we ran to and fro with our hats, getting water in them from the roadside ditch and throwing it over the calf’s head. The patriarch looked on in sorrow and scepticism.

‘Poor calf,’ we said, fondling its ears.

‘Not the calf is poor,’ said the patriarch, ‘I am poor.’

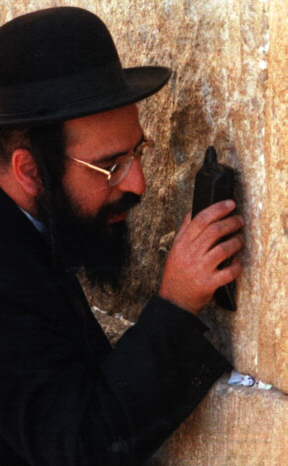

We hardly knew it then, but it was the last smell of the old-time eastern European brew any of us were going to get for a long time. At Uzhorod we even talked to a ‘Wonder Rabbi’ – a rabbi who worked miracles. Before him there had been a more famous wonder-rabbi at Uzhorod, who, as a result of a vision, had defeated the Russians when they were sweeping in on the place in 1915.

The wonder-rabbi we met was his son-in-law, had come from somewhere in Poland and married into the business. As son-in-law of the Destroyer of the Cossacks he had prestige too. Also he deserved it, because though Mr Delmer and I visited him at fairly short notice, when we got there he had a copy of the Daily Express on his desk. It had been rushed in during the twenty-four hours between our request for audience and our arrival. It was the first copy of the Daily Express ever seen in Uzhorod. But the rabbi was at pains to tell us that he read the Express carefully every day. His favourite newspaper.

The courteous trouble taken made us, in our turn, feel very polite, very gentle. Nevertheless I had to say to him, ‘Do you, in fact, work miracles?’

He fluttered a white hand and very gently sagged a splendid black beard.

‘I mean’ – I said, or Mr Delmer said – ‘the people here most certainly suppose that you work miracles.’

‘The common people,’ said the rabbi, ‘have a tendency to superstition. Also they tend to confound the material with the spiritual. They see a man; a rabbi; learned; a profound student of the Talmud; a holy man, in fact! So they think "the spirituality of such a man must be expressed in some unusual material powers". So they believe I can work material miracles.’

‘And your own attitude to this mistaken tendency? You take steps to counter and expose such false conceptions?’ ‘You would do well to remember,’ said the rabbi stroking his beard, and looking with an air of interest at the Daily Express, ‘that every false conception contains, nevertheless, a kernel of truth.’ (pp. 9-10)

Was Poliakoff a Jew?

Oddly – or perhaps not so oddly, because I have always liked Americans, and the sort of man that likes Americans is liable to like Russians – a prominent light in my part of the gloom was my old friend Mr Vladimir Poliakoff, formerly diplomatic correspondent of The Times. (It was he who had first, perhaps inadvertently, provided the information which ultimately led to the discovery – or invention, as some said – by The Week, of the famous – or notorious, as some said – ‘Cliveden set.’)

With the head of a Slav generalissimo, and a get-up vaguely suggestive of Homburg about 1906, this Vladimir Poliakoff strode and occasionally tiptoed around and about the diplomatic world of the twenties and thirties like a panther, which duller features deem merely picturesque or bizarre until they note what a turn of speed he has. Among his other notable qualities was an infinite capacity for taking pains to do everyone, from ambassadors to train conductors, small but unforgettable favours. A colleague, who regarded the very existence of Poliakoff with jealous disapproval, declared that there was not a foreign secretary in Europe whose mistress’s dog had not been smuggled across one or other frontier by Poliakoff.

I met him for the first time in 1929 when I was tenuously attached to The Times office in Paris. The atmosphere in the office on that day was sulphurous. The chief correspondent, on calling to see the Minister of Foreign Affairs, had been informed by the chef de cabinet that ‘Your chief has just been with the Minister for an hour.’ The correspondent was at first merely amazed that the editor should have come over from London without informing the office. Later, to his disgust, he learned that the supposed ‘chief’ was the peripatetic Mr Poliakoff on a quick trip to Paris. By virtue of a certain manner he had, he was quite often taken by foreign statesmen to be the ‘man behind’ everything from Printing House Square to Whitehall, and his sincere denials merely confirmed their belief.

Furthermore, the assistant correspondent had been apprised by friends in London that Poliakoff was accustomed to refer to him slightingly as ‘the office boy with the silk moustache.’ As a result of all this, the chief correspondent shut himself up in his room, his assistant put on his hat and walked out, growling, and I, to my alarm, was left alone with the internationally distinguished Poliakoff. I saw him examining me with attention, and feared he would ask me high diplomatic questions which I should be unable to answer, and thus become discredited.

He said, ‘What you have is the grippe. Your temperature – I am not accustomed to be wrong about such things – is a little over a hundred.’ Astonished, I admitted that this was precisely the case. The tails of his grey morning coat flapping suddenly behind him, he bounded from the sofa.

‘A-ha!’ he shouted. ‘I am the one to cure that. A special remedy. Ordinary ones are futile. I proceed at once to the chemist on the corner to give my instructions. Relax. I shall return.’ In ten minutes he was back and, seating himself beside me, took from his tail pocket a small clear-glass bottle from which he poured a few drops of liquid on to a huge silk handkerchief. ‘Breathe deeply. Inhale the remedy of Poliakoff.’ He had his arm round my shoulder and held the handkerchief to my nose with the air of a field-marshal succouring a stricken private. The result was immediately beneficial. But I noticed too that the smell and general effect were exactly those produced by a well-known, widely advertised popular remedy, the name of which I have forgotten. I was sufficiently curious to inquire later from the corner chemist whether a certain gentleman – Poliakoff was easy to describe and unforgettable – had, a little earlier, bought a bottle of this well-known product and arranged for it to be specially decanted into a plain bottle. Such had, the chemist said, been the case.

I found this little manoeuvre, this taking of so much trouble to please, both impressive and endearing, and years later, when I had left The Times, was delighted to renew acquaintance with Mr Poliakoff at some diplomatic reception in London or Paris. (pp. 16-17)

‘Monsieur Bob’ Hints at the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

We used, in that strange spring before der Pakt and the war which we all erroneously thought was going to be the end of everyone, to take, sometimes, the pleasant air of Touraine, in the company of a man whose real name I have never known nor asked – he was called simply Monsieur Bob. His parents were wine-growing peasants in Touraine, and he himself – I have been told, and I think it is true – was an officer of some French cavalry regiment which was attached (either as guard or demonstration) to the French Embassy in Russia at the time of the revolution.

Whether it was cavalry or not, the fact was that when the showdown came – when the French were supposed to rush at the revolting proletariat – this young officer refused to order them so to do. Indeed he ordered them, and they seem to have acted with vehemence, to assault the other lot – the Reds. At any rate, whatever it was he did was heinous, and he was sentenced to death in France, should he ever return to the jurisdiction. In the end there was an armistice on that sort of thing – I suppose as a result of the Franco-Soviet Pact (these things always seem of life-and-death importance at the time and afterwards you forget what on earth the sequence really was). So there he was in France, a gentle, dapper little man cocking a Touraine peasant’s eye at the Comintern of which he was a principal agent.

I had met him a couple of years before in Spain, where he had arrived suddenly on a tour of inspection. I had expected someone grim who probably would weigh me in the balance and find me much wanting. I took a terrible chance by recommending to him – a Tourangeois – a certain Catalan wine I had discovered, telling him that it was as good as a medium-grade French claret. Fortunately, for he was a fastidious little man, he thought so too, and we became friends over the first bottle.

Occasionally, when there was time, he would drive me and one or two other wine-lovers such as Kisch, down to his parents’ vineyard. They were a gnarled old couple, looking as though they had been toiling in that vineyard since about the time of Voltaire. And although neither of them had ever been farther from home than Tours, they thought their son’s sensational and even bizarre career quite a natural thing to happen in the world. On account of their almost rigorous hospitality, after a couple of hours at their farm-house one lived in a golden haze. They would open a bottle of their wine, give you a glass and ask what you thought of it.

You drank and commented admiringly – and it really was very good.

The old man would look at you as though he had found himself entertaining an escaped lunatic.

‘Good? You think that good? But my dear sir, forgive me for asking, but where have you been all your life? Now permit me to draw your attention to this bottle. You will see the difference.’

You drank a glass or two of the next bottle, and you did see the difference and said so.

‘Wonderful!’

‘Wonderful? You can find that wonderful? Good, yes, I agree. But not wonderful. Now nearer to being wonderful is this.’

Bottle after bottle was opened on a deliciously ascending scale, until the peak of the sublime was reached. Once, ignorantly, I remarked of the last, the most sublime bottle of all, that it must fetch an enormous price in Paris. My host jumped as though at an indecent suggestion.

‘Sell that to Paris? My dear sir. That is our best wine. We can’t sell that. We drink it ourselves.’

It was during one of these golden interludes that Monsieur Bob first sought to convey to me, with infinite discretion, the possibility, theoretical as yet, of something in the nature of a German-Soviet Pact. To most of us at that time the notion was both outrageous and incredible. And if rumours were heard, we supposed them to have been put about by reactionary agents.

‘But if,’ said Monsieur Bob, sighing deeply and stroking the stem of his wineglass, ‘the British simply do not want to come to a serious agreement with Moscow?’ (This must, I suppose, have been in late May or early June.) ‘Suppose,’ he said, ‘that le patron’ (it was the way Stalin was always referred to at that time), ‘suppose le patron – on the basis, you understand, of information received – believes that secretly the British still hope to come to an agreement with Hitler themselves? An agreement which will send him eastwards instead of westwards? What do you think le patron would do? What could he do, except perhaps turn the tables on them and buy a little time for Russia by sending him westwards first, en attendant the real battle in the east?’

‘But good God – an agreement with Hitler? With that aggressor and murderer, the leader and organizer, after all, my dear Bob, of anti-communism everywhere?’

‘Are all Scotsmen,’ asked Monsieur Bob, oddly echoing Poliakoff, ‘somewhat romantic? I would draw your attention to the fact that we are talking about serious international politics. But of course nothing of the kind may ever happen. Perhaps London will all at once come to its senses. I have great faith – perhaps it is I who am now being romantic – in English common sense. Perhaps’ – and it was a phrase you heard over and over again in Paris at the time – ‘perhaps they will send for Churchill and put an end to all this fooling about.’

Perhaps it was the wine, perhaps it was the fact that Patricia was due to come over to Paris in a day or two – for whatever reason, I paid at the time too little attention to this conversation in which, as I saw later, my friend Bob was seeking to offer me, from his own inside position, a cautious preview of the possible shape of things to come. So that when, a good many weeks later, the first unmistakable indications that der Pakt was going to be a reality came, soon after midnight, over the tickertape at the Savoy Hotel in London, I was almost as startled as anyone else. (pp. 34-36)

Announcement of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact: ‘AII the Isms have become Wasms’

The idea that the whole thing had been reduced to an absolute farce was, with more or less justification, according to your viewpoint, the first reaction of millions of honest Britons to the news that ‘hammer’ Molotov and champagne merchant Ribbentrop were together in Moscow, arranging to be friends for evermore. Witty, encouraging and inaccurate to the last, the British Foreign Office spokesman said, ‘AII the Isms are Wasms.’

No one old enough to have been politically conscious at that time is likely to forget the bubble of passions, the frantic accusations and counter-accusations, the ‘agonizing re-appraisals,’ the reaffirmations of faith, the hubbub of emotions, which thereupon broke out. And, of course, people too young to have been there must by now find a lot of the excitement irrelevant and incomprehensible. It was real enough that night. (p. 39)

Winston Churchill and Bernard Baruch. A Gaullist Murder in Duke Street

At that time the Gaullists were far from popular in London – partly because they were still less popular in Washington, where President Roosevelt took the view that, in terms of Rooseveltian philosophy, the relatively small de Gaulle bottle must be marked ‘dangerous, to be taken only under American doctor’s directions’ like the much bigger bottle in which Roosevelt thought he smelled the inveterate imperialism and colonialism of Winston Churchill. The much over-simplified impression one had at the time was that Mr Churchill, who had his own troubles with Mr Roosevelt – not to mention the general and real undesirability of doing anything which might be difficult to explain to Mr Bernard Baruch – saw no good reason to compromise British policies by getting their name too closely linked with that of General de Gaulle.

Liberals and Socialists in France and England were suspicious of the General too. Indeed, I suppose that if you made up a composite figure of every available element that would annoy, discompose, and arouse the suspicions of an orthodox English Labour Party leader, the General would have about filled the bill. He may have made, from time to time, some enthusiastic speech about democracy or the century of the common man, but, if so, I do not recall it. And the omission was a serious political mistake. It was one which M. Laguerre and myself did our best to repair. We were not much assisted by the attitude and actions of the members of his entourage. There was a group – in organizations of such a kind there always is such a group – which felt that what other members of the organization did not know would not hurt those members. It was the kind of group which can never grasp the difference between that sort of killing which the public is going to think is murder, and the sort which the public can be induced to accept as a form of national defence.

As a result of this attitude, a man became murdered in Duke Street. The people responsible believed – I personally have always thought that they were right in so believing – that this supposed loyal adherent of the Free French was in reality a Nazi spy. The victim, after death, was strung up in this room in Duke Street and the police were supposed to believe that he had hanged himself.

The police found it difficult to understand why a man should savagely beat himself up before stringing himself up. Also, since it was the ordinary police who had been called in to view the body of the alleged suicide, the case had been automatically placed on the conveyor-belt of the ‘due processes of law’

It was the sort of point which ‘the group’ was liable to overlook. Perhaps they would have been more careful about it if they had not misunderstood – and who shall blame them? – the nuances of the British political scene. They did not evidently understand that in British political life it is almost essential to be a Christian even when you are an atheist. ‘Being a Christian’ in this sense means that, though you may proclaim total disbelief in the doctrines of the Church, you must at the same time indicate that you are in favour of Christian ‘ethical values’

To sneer at this as hypocrisy is cheap. There is hypocrisy in it, certainly. But, when the people across the street are running up their extermination chambers and getting to take torture for granted, this sort of hypocrisy has a value. Wilde said hypocrisy is the tribute vice pays to virtue. Such tributes, and the recognition that they ought to be paid, have a civilizing influence.

Being, in this sense, Christian, British public opinion – and more particularly Left opinion – is implacably opposed to war. When, after announcing its opposition, the Left, as in the last two world conflicts, finds itself vigorously supporting a war, it understandably prefers that it shall not have its nose rubbed in the facts of war more than is absolutely necessary. It requires, for instance, that if in the interests of the war effort a man has to be done to death in Duke Street, the murderer shall wear kid gloves and leave no finger-prints. Enemy agents, like the ex-husband of the heroine of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, are not murdered, they become shot.

A disclosure that the Gaullists considered it natural and reasonable to murder a man in a back room in Duke Street on the ground that they thought him an enemy agent was going to be meat and drink to de Gaulle’s enemies. Liberals and Labour people were going to react with horror on general principles. And a lot of other people who would have thought nothing of doing the same thing in similar circumstances were going to exploit what one of them once deliciously described to me as the ‘layman’s reaction’ zestfully for their own purposes.

The case has always fascinated me as being one of those affairs which have effects similar to that which imminent drowning is supposed to have, except that in these cases it is not the past which is projected in a sudden illuminating flash, but the present. By just watching the reactions of people – of those, that is, who knew or guessed the truth of what had happened – you could acquire a detailed geographical survey of the mind and face of political Britain, a sketch of trends and tendencies you could not have got from innumerable ‘public opinion polls’ Characteristically completing the picture, the group simply could not see why, once the body was literally on view, the British authorities could not dispense with an inquest, or else instruct the loll police to say that the man had been picked up dead in the street, or tell any other story of the kind which would avoid any type of political unpleasantness. Indeed it was one of those episodes which helped to convince the Gaullists that the British Intelligence Service – for whose assistance in burying the matter quietly they immediately applied – was positively working against them.

Otherwise why was not an agent sent round to arrange for people, if they had to appear in public, to say the right thing? On est trahi. Although I did not think so at the time, I have been told that, within the limits of English legality – which were far from satisfactory to the French – the best that could be done was done. But although, by skilful use of the security regulations, the barest minimum of fact got published in the newspapers, the story circulated widely by word of mouth, and André Laguerre, with such assistance as I could offer, had to work overtime trying to keep the General’s picture among the political pin-up favourites of the public at large.

Things would have been easier for us if it had been true, as was so widely asserted, that the General had no sense of humour. He was represented as an austerely unbending, rigid type of man who ‘joked with deeficulty’ – who could not, it was said, joke at all. To suppose so was to misjudge him seriously. In my estimation, at least, he could not resist a joke even when to play it was obviously against his best interests. Most of his jokes were about as harmless as a hand-grenade after the pin has been taken out. (pp. 79-82)

De Gaulle’s Sense of Humour

At one time the Free French employed in London – much in the way that people employ hard-up peeresses to lead their daughters round the season – a highly connected but quite broke socialite to run a sort of salon for them. She gave lunch parties and dinner parties where loyal Free Frenchmen met English men and women of influence. (M. d’Astier de la Vigerie, who used to parachute, near-suicidally, in and out of France like a ping-pong ball, told me once of attending a dinner of this kind when an English cabinet minister and his wife were present. They were not unaware of the heroic doings of M. de la Vigerie. ‘Are you,’ the Minister’s wife inquired, ‘planning to return to France soon?’ M. de la Vigerie, hardly able to believe his ears on hearing this fantastic indiscretion, replied to the general effect that that was as might be. Undiscouraged, the ministress pursued her investigation. Would he, as and when he dropped from the skies into occupied France, be going anywhere near Bourges? Thinking, ‘Good God, are these people having a war or not?’ Vigerie replied that all things were possible. ‘If,’ said the minister’s wife, ‘you do happen to be in Bourges, I wish you would make a point of looking up two old servants of ours who returned there when we left France just before the invasion. I should like to let them know that my husband and myself are quite all right. You see, they may be anxious about us.’)

After a while, it was decided for some reason or other that the salon-runner was not really earning her keep. I have forgotten whether the reason was that things were going so well for the Free French that she had become redundant, or were going so badly that even a good salon was not going to make much difference. It was decided to sack her. But de Gaulle’s closest advisers were worried – she was a woman still of potential influence; the thing must be done with the utmost discretion. ‘Discretion, General,’ they said, and de Gaulle contrived to look as though discretion were his middle name.

They cooked up the idea of a little tea-party at Carlton Gardens where the General and one or two of the discreet advisers were discreetly to break the news that, great as this lady’s services had been to the Cause, the Cause with the utmost regret was compelled, temporarily it was to be hoped, to relinquish them. The discreet, sighing with relief at the fact that things were going to go so smoothly, waited for her arrival. She was announced. De Gaulle, uncoiling suddenly from his chair like a long worm with a steel spring in it, strode beaming across the room to greet her.

‘A-ha! Madame,’ he said, ‘the first thing I want to tell you is that you’re sacked.’

Even months later he recalled with pleasure the expression on the faces of the discreet advisers at that moment. (pp. 83-84)

Why the Nazis Locked Up Jews

Naturally it was not without a great deal of trouble, and noble assistance from the National Union of Journalists, 90 per cent of whose members detested what I said but took a fine Voltairean attitude about my right to say it, that when (after the fighting men had driven the Germans and Italians out of North Africa) it was agreed that a party of diplomatic correspondents should be allowed to visit the scene, I was permitted to make one of their number. I have it on what I consider good authority that Mr Bracken – despite all – took a determined attitude about this, and insisted that to exclude me would be a picayune sort of politics. If it is true, I owe him a debt of gratitude. And of course if not, not.

However, when we got to Algiers – we had been there I think about twenty-four hours – two rather disconcerting things happened. The leadership of the prewar Communist Party of France, a great parcel of ex-MPs who had just been let out of jail and seemed to have heard of nothing since August 1939, made it clear to me that in their view Communist policy in London towards de Gaulle had been grossly mistaken – the man was a menace, an anti-democrat, and an embryo dictator. They seemed, indeed, to be contemplating some kind of alliance – or perhaps they already had such an alliance – with the Giraudists. And I could not escape the discouraging impression that, because the assassin of Admiral Darlan had been a Royalist extremist of the Right, they disapproved even of that act.

The other upset to my schedule occurred when I was summoned to the relevant British authority – the Information people, I suppose, but I no longer recall who actually acted in the matter – and informed that I was expelled from North Africa and must take myself off within twenty-four hours. An aircraft would have a seat for me at Maison Blanche on the morrow.

It seemed a sad thing to have come all this way and have to return so soon. And I must confess that I was a good deal influenced by considerations other than those of political and joumalistic achievement. The sun was wonderfully hot, and after the war years in London Algiers danced in the sun like a dream come true. I made up my mind that whatever happened I really could not quit the scene so soon.

Moreover it was apparent to me that whereas the British had allowed me in, and were quite prepared for me to stay, the Americans were having an early attack of those security jitters which later developed into neuroses really harmful to those otherwise vigorous and healthy people, and had taken fright. They were in fact raising Cain with the British for having allowed me to become airborne Africa-wards in the first place. One more example, they were saying, of the sloppy British way of doing things. And the British were, at that moment, in no position certainly at least in no mood – to make an issue of it, and find themselves quarrelling with their great and good friends over the case of a Communist diplomatic correspondent.

It seemed best not to be, for the moment, an issue; in fact, to disappear. I took refuge in the house of an elderly and heroic Jewish doctor – a man who before the allied landings had risked his life over and over again in big and small (but continuous and relentless) actions against the collaborationists and the Germans and the Italians, and in whose house a part of the planning of the landings had actually been carried out. He was not only old but lame. When his big house was full of hidden conspirators he had been used to spend hours and hours, from dawn onward, limping wearily from market to market so as to buy food for a dozen young fighting men without attracting undue attention by the quantities he bought. I can think of no one I have ever known who, in his courage, physical endurance, skill and cunning in the face of enemy attack, and ability calmly to cultivate his cultural garden when he had a moment free from the threat of torture, was superior to that man.

It was in his house that the assassination of Darlan had been planned, and the assassin had been hidden there for some time before the act took place. There had been, as there always is in such affairs, some sort of muddle and, although I naturally did not ask questions about it, I gathered that somebody had, as the saying goes, jumped the gun – the thing had not been supposed to happen in exactly that way or at exactly that time. However, as I say, this is simply an impression I gained indirectly in the doctor’s house.

It was a fine house to lie low in – several exits available and a favourable concierge. My notion was that, by keeping out of the way and not making myself into any sort of test case between the mutually embittered British and American authorities, I could probably avoid being physically thrown out of North Africa for at least a while, and at the same time – that house being the kind of house it was – could probably, in the ordinary course of conversation with the characters who stayed or visited there, find out more about what was really going on than I could have hoped to do in any other way. (pp. 84-86)

Birth of the United Nations. Media-Inspired Religiosity

Early in 1945, I found myself on a ship packed with diplomats; with hundreds of expectant mothers, brides of Canadian soldiery now being suddenly removed, by some War Office whim, to their new homes; with scores of journalists of numerous nationalities; with a sprinkle of expert intellectual mechanics from the garages where Anglo-American relations go for repairs; and with the customary number of professional spies – some masquerading as diplomats, others as journalists. The world being what it is, I dare say some of the expectant mothers were doing part-time espionage in order to defray the high cost of childbirth.

The journalists, the diplomats, the experts and the spies were all bound for the foundation meeting of the United Nations at San Francisco.

The vessel was quite large – around 20,000 tons, as I recall – but because most of the accommodation was required for the mothers-to-be, the rest of us were somewhat confined. The only ‘public room’ available to us was a small, perpetually crowded saloon. Otherwise, you could lie on your bunk listening to the repeated explosion of depth charges from the destroyers protecting our convoy (for it seemed that at this eleventh hour of the war the German submarines were seeking to put on a worth-while finale to their show), and wondering what chance one would have if one of the submarines got through and the cry was raised ‘women and embryos first.’

A voyage which might otherwise have been almost intolerably tedious was transformed into a pleasure chiefly by the accomplishments and charm of Sir John Balfour, who had been British Minister in the Embassy at Moscow, and was now being transferred to the same position in the Embassy at Washington. His impersonations of Stalin and Molotov were in themselves enough to take anyone’s mind off torpedoes and a shortage of whisky. I reminded him of how, years and years before, when I was a student in Budapest and he was Second Secretary at the Legation there, we used to play a game (his own invention, I believe) which might be described as a kind of literary Consequences. I have forgotten just how it was played, except that it involved inventing the title of a book, inventing a suitable name for the author of such a book, and writing a long review of this non-existent work.

This game we now revived, and for hours on end four or five of us sat at a table in the comer of the saloon, scribbling and passing our sheets from hand to hand in the manner of consequences. (‘The Odious Paradox’ was one of our titles. ‘Now this, obviously,’ remarked Balfour, ‘must be a biography of Claud.’) The amusement of the game was enormously enhanced by its effect upon the spies who hung around the table with flapping ears and bulging eyes. The scene, they obviously felt, must mean something, must have some kind of international significance. How could it be otherwise than significant than to have there, huddled round the corner table of that rolling saloon, writing notes to one another, concentrating deeply or bursting into incomprehensible laughter, the new British Minister to Washington; the diplomatic correspondents of The Times, the Daily Mail; a notorious Communist; Mr Cecil King, the effective controller of the Daily Mirror; and Professor Catkin, who was believed by many to be on a secret mission from the Vatican to the State Department.

The spies’ nerves were fraying fast. Day after day they crept nearer and nearer, breathing down our necks. At length Balfour, not a man to tolerate much intrusion, jerked round suddenly, his cigarette in its exceptionally long holder aiming like a lethal weapon at the peering eye of some Spanish or Swedish sleuth.

Startled and embarrassed, the sleuth stuttered out something about natural interest, just wondered what we were doing, whether it was a new game, or what? ‘We are engaged,’ said Balfour, ‘in writing imaginary reviews of imaginary books.’

The sleuth tottered away, wounded. You could see that he felt his intelligence had been abominably insulted. Surely, he felt, they could have had the courtesy to invent a more credible lie than that?

We were in mid ocean, celebrating, indeed, my forty-first birthday, when President Roosevelt died.

There were no Americans aboard, and the grave, perhaps momentous, event and its possible consequences were discussed and analysed gravely but calmly, like any other important and sudden occurrence. The experience of these last few days at sea, before we eluded the last submarine and ran safely into the harbour of Halifax, Nova Scotia, served, by contrast, to intensify its tremendous, explosive impact on the United States at that critical moment of its history. In England, as I have remarked before, it takes nothing much less than a major air-raid or a general strike to produce any immediately perceptible change in the social atmosphere. But the United States lives more externally, more expressively. In the electric streets of Chicago, in the gossip-laden muddle of a barber-shop, or the chillingly streamlined and flamboyant luxury of a millionaires’ club on a sky-scraper, no one could escape for a moment the awareness of this as an eve of great decisions. One was aware too – and a good many of the European visitors were more than a little scared by it – of the vast, dynamic confusion of American politics. Some of those who were confronted with it for the first time had the air of a person who has come to seek advice and support from an immensely rich and immensely respected uncle, and finds the old rip half drunk and boxing with the butler.

The journey of our special train across the Middle West, still (to anyone who feels strongly about people and history) one of the most exciting regions of the earth, was at times almost intolerably moving.

Our heavily laden special had some sort of notice prominently displayed on its sides, indicating that it was taking people to the foundation meeting of the United Nations. In a natural way, the emotions aroused among Americans by the death of Roosevelt and the impending birth of the United Nations had fused in the public mind. From towns and lonely villages all across the plains and prairies, people would come out to line the tracks, standing there with the flags still flying half-mast for Roosevelt on the buildings behind them, and their eyes fixed on this train with extraordinary intensity, as though it were part of the technical apparatus for the performance of a miracle. Often, when we stopped at what seemed to be absolutely nowhere, small crowds of farmers with their families would suddenly materialize, and on several occasions I saw a man or woman solemnly touch the train, the way a person might touch a talisman.

Then I remembered how, many years before, when Dr Einstein first crossed the United States, the papers had carried stories of people who had come for miles just to touch the train in which the savant was travelling. In New York such people were derided. Since they knew nothing of higher mathematics, they must be the victims of hysteria. (In one place, it is true, a group of women were reported to have believed that if they could but touch Einstein’s coat, their children’s sicknesses would be cured. The same sort of thing, the late Michael Arlen once told me, happened to him when he visited the United States after the almost unprecedented success of The Green Hat. In his case it was buttons that people seemed to want, believing that a button from the clothing of such a man would be a charm and talisman – any button: jacket, waistcoat or fly.)

The attitude to Einstein still seemed to me a good omen. Naturally one might prefer that people should not be superstitious or hysterical at all. Just for the moment, at any rate, it cannot be denied that these tendencies exist. It was in my mind that if the people are going to be hysterical and superstitious about film-stars and dictators, it is at least somewhat encouraging – a movement of an inch or so in the right direction, than which no more can be realistically expected – that some of them some of the time should feel the same way about a man because they believe him to be the greatest thinker, the most learned sage, of the epoch.

Now people of this kind looked into the club car of our train, and one was disconcertingly aware that, in this normal collection of the competent and the half-crazy, the idealistic and the hard-boiled, the neurotic and the humdrum and the drunk, those people outside were seeing a powerful instrument for the securing of world peace. (pp. 98-101)

The Nature of the Tribe

At two o’clock on an icy morning the central station at Sofia seemed like an uncomfortable end of the world. Bugs bit like stinging hornets, lice surged from the floor, much of it covered by sleeping peasants. There was no sign of any transport to the centre of the town. Nobody present, it seemed, could speak anything but Bulgarian. I got very weary of bending over snoozing men in woolly caps and jabbering at them in German until they shook their heads and dropped off to sleep again.

Then Patricia said, ‘There are three men in felt hats. They look like our last hope.’ I approached the group, who, by the mere fact of wearing hats, achieved an almost cosmopolitan appearance. I tried German: no dice. French: total incomprehension. English: shaking of hats. Despairing and feeling a little mad, I addressed them in Spanish. Their eyes lit up. They understood, and replied in what was certainly intelligible as a form of Spanish – though a very strange form.

Volubly, their olive-coloured hands flying and fluttering, their dark eyes dancing, they gave us all needed information, volunteered to telephone for a taxi-cab. While we waited for it, I remarked that it was rather odd to find Spaniards here. They explained. They were not Spaniards but, one of them said, ‘Our family used to live in Spain before they moved to Turkey. Now we are moving to Bulgaria.’

Thinking that perhaps they had been ‘displaced’ from Spain by the upheaval of the civil war, I asked how long it had been since their family lived there. He said it was approximately five hundred years. I did some quick reckoning and realized that their move had been made under the pressure not of Generalissimo Franco, but of Ferdinand and Isabella. They were the descendants of the Marrano Jews – Jews who had, in the centuries before Ferdinand and Isabella, renounced Judaism for Christianity, hoping thus to live and prosper in Spain. It had done them no good. They were routed out by the Inquisition and expelled just like those who had never bothered to get converted. But their language remained a kind of Spanish Yiddish. He spoke of these events as though they had occurred a couple of years ago. How long, after all, sub specie aeternitatis, is five hundred years? They planned to live now by selling sewing-machines. (pp. 142-143)

From Claud Cockburn, Crossing the Line, MacGibbon & Lee, 1958