|

Not So Land of the FreeSimon Sheppard recounts his career as an international thought-criminalWritten from HMP Wolds and published in Heritage & Destiny magazine, January 2011 |

I arrived at HMP Wolds, via Armley jail, Leeds, from Orange County, California. Or rather, from Santa Ana City Jail. I didn’t see much of America except from the windows of a prison van or one of those big prison coaches you see in films, but I heard plenty of stories.

The adventure began when my co-defendant and I fled bail and flew to Los Angeles to seek political asylum, since what we’d done wasn’t illegal in the USA. I was prosecuted chiefly for publishing a satirical comic book Tales of the Holohoax. It mocked Elie Wiesel’s claim to have seen geysers of blood spurting from the ground where Holocaust victims were supposed to have been buried, and comparisons were made with implausible, ancient Talmudic accounts of the mass destruction of Jews. The comic, of American origin, had been informally circulated in Britain for around twenty years, so it had to be legal, I thought. I was prosecuted for possession of hard copies of the comic, but distribution of the online version from a web server in California, making my co-defendant and I the first ever to be prosecuted under the Public Order Act for distribution of “racially inflammatory material” from out of the jurisdiction. We were convicted on the basis that the web pages were “available in England and Wales,” just like any other website anywhere in the world.

My co-defendant Steven Whittle had not published, only written, but he was convicted under “joint enterprise.” He had been an internet columnist focusing on the people who pulled our government’s strings, often from behind the scenes. Naughty words were used.

When the first guilty verdict came, as we were desperately clutching at straws, we were given some very bad advice. The Americans couldn’t possibly refuse us political asylum we were told, since the website was perfectly legal there, being protected under the First Amendment of the Constitution guaranteeing free speech. Symbolically we were to head for California, since that was where the server hosting my www.heretical.com website was located. We were told that the Americans would probably hold us for a couple of days then release us.

It turned out we’d headed for ground zero and we were immediately incarcerated pending the outcome of our asylum applications. Since, as instructed, we had declared ourselves to the first official we met, we had never passed through customs and officially set foot on American soil, and this allowed the immigration authorities to do anything they liked with us. No other country is as generous to asylum-seekers as Britain is, and the USA, with two million of its citizens behind bars, is one of the countries most likely in the world to lock people up.

Air-conditioned Hell

The first three days were a nightmare, spent sleeping off our arduous journey through Ireland on the concrete floors of cold tanks full of strange faces. I’d wake up staring into the eyes of some Mexican desperado who, for all I knew, was some hardened gang-banger who would kill me without a qualm. If it hadn’t been so cold – I learnt later that the place was super-chilled to reduce the spread of disease – I might have thought I’d died and gone to Hell.

At one point we were loaded onto a big prison coach and driven north to a facility at Lancaster run by the US Marshals. The coach was very impressive: brand new, six wheels, heavily armoured throughout and with TV cameras in the cab monitoring the prisoners behind. I think the bus was automatic, and probably did a lot less than ten miles to the gallon. The payload was all chained together, and I remember one prisoner claiming that he had tuberculosis, which I had a great fear of contracting. On screening soon after our arrival at Lancaster, against my advice, Steve confessed to medical problems and I did the same to ensure we stayed together, which I only just got away with. Then we were put back onto the prison bus and returned to the tanks at Los Angeles.

Alphabet soup

America has many different police services: there’s a bewildering list including Marshals, Sheriffs, State cops, Highway cops and the FBI. We were held on the orders of another federal agency, the Department of Homeland Security (headed by ex-KGB chief Michael Chertoff). We ended up in a new jail run by the city of Santa Ana, in the southern-most part of LA. The jail was paid $84 per day per inmate and earned $5million per year for the city.

In the US, as well as there being different kinds of police, there are many different kinds of jails. There, ‘prison’ and ‘jail’ are different: jail is for up to twelve months and prison anything above that. If you commit a federal crime (such as a bank robbery) you automatically go to a federal prison, and serve 85% of your sentence with good behaviour. The feds are awash with money, so conditions aren’t too bad. The State and County institutions are the opposite, crowded, short of money and often run at a profit for the benefit of Mormon shareholders.

Santa Ana City Jail was modern but austere. Since, exceptionally, it had proper medical facilities, many prisoners had been allocated there because they had diabetes or other problems. Consequently the food wasn’t bad, but it was meagre. There were no TV’s in the cells and smoking wasn’t allowed anywhere (while we were there, California even made smoking on a public beach illegal). What I found most surprising considering the American emphasis on the mighty dollar was that the few prisoners who worked in the jail – serving the food trays we carried back to our cells, and being unlocked at 2am to clean some other part of the jail – did it voluntarily and only in exchange for extra food and being allowed to sit in front of one of the dayroom TV’s for a few hours. In contrast, the connection charge for a telephone call started at $8; a single local call to our attorney had cost over $16. No wonder there were telephones wherever we went. There was no “cell wage” and no regular work for prisoners; if you didn’t have money sent in, you had nothing.

Our module consisted of 32 double cells on two floors, with each cell having an opaque window on the outside wall about six inches high and four feet wide. Sometimes there was a gap of a millimetre or two between the glass layers through which you could see the outside world. The door was unlocked with a mobile phone-type device and a reinforced glass window allowed the guard to look in at any time. Torches were often shone in at night. We were never prisoners officially, but “immigration detainees”; not that it made any difference. The doors were still locked.

|

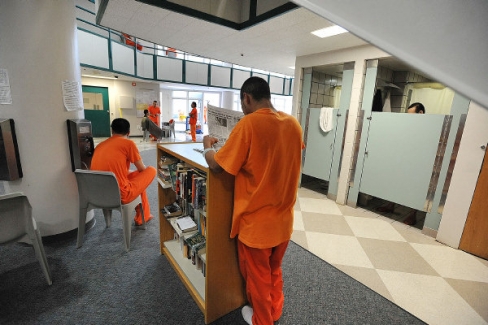

| Outside the cells in Santa Ana Jail. I remember some women from the Orange County Register coming round taking these photographs. I stayed out of the way, feeling a bit like an animal in a zoo. |

Passing time

The days were so uneventful that they passed quite quickly. We occupied our time sleeping, reading and writing replies to the many letters from supporters we received. I wanted to thank them individually, because their letters of support and encouragement made a great difference. They also sent us several hundred dollars to pay for drinking chocolate, stamps and other luxuries.

A favourite pastime was thinking up amusing nicknames for the guards. Only one guard occupied a station for the module, logging razors out and in at the start of the dayroom session and handling other mundane matters. However if too many staff decided to take a day off, as sometimes happened at weekends, we could be left locked up all day. We suspected that the facility was as much a sinecure for fragile and convalescing law enforcement personnel as much as a housing for delicate prisoners.

The best of the guards was “Mr Big,” a gentle giant originating from the South Sea Islands. The worse the guard, the more convoluted the nickname had to be, in case it was overheard. Undoubtedly the worst was “Flossie,” a short, dumpy, slightly Oriental-looking woman with a shrill voice and domineering manner. Her voice had been the inspiration for the nickname, deriving from the song of a nightingale. Tales of the havoc following in Flossie’s wake abounded, and she was later assigned to laundry supervision, probably so as not to inflict her on any one module.

Other, identical modules in the facility housed women and federal prisoners. In the module below ours the inmates were out of their cells all day and divided themselves along racial lines, as is the norm in American jails. The regime in our module was determined by the number of groups the authorities had to keep segregated from each other, and “dayroom time” had to be divided between each.

Tragicomic events

Things got harder with the arrival of half a dozen Mexican “ladyboys”: transsexuals who were still officially male, probably brought in following a brothel raid. This split our module into three groups: our own, with one or no offences; the serious offenders, and the transsexuals, each having only two or three out-of-cell hours each day. The ladyboys at least provided some entertainment, coyly flirting with other inmates through the cell-door windows, and dressing up. Some even had breasts. I vividly remember one announcing to the module, “I’ve got a visit from my boyfriend,” clearly audible through the cell doors. It was Proclamation of Enhancement.

A particularly tragicomic event concerned a Mexican Southsider (i.e. gang-member) whom I shall call Sanchez. He at one point had attacked my British cell-mate Alastair, though not seriously, so there was no love lost. After fighting deportation for several months Sanchez lost his case, and was taken to the departure station from which coaches regularly carried deportees over the Mexican border. We occasionally stopped there on the way back from the immigration court. Sanchez was to be loaded onto a bus imminently departing, but asked to be taken back to Santa Ana so he could pick up some possessions he had left with his cell-mate. The bus departed and then, as he was sat waiting, a call came through to the desk. Sanchez heard his name mentioned, and the officer responded “Yes, he’s still here.” It turned out that he was wanted by another county on further charges. Sanchez revealed to those sitting next to him that this was his “third strike,” and thus now potentially faced a 25 or 30-year sentence for the sake of picking up a few worthless odds and ends from his cell.

Other inmates were Honduran, Cuban, Nicaraguan and so on but the majority were Mexican. White faces were relatively rare. A Ukrainian seafarer came and went who had just been given command of his own ship, and had celebrated prematurely by getting drunk as his ship approached LA harbour. Another was a Swedish car mechanic who’d been in the country twenty years but had never got round to completing his citizenship papers. He’d been incarcerated after his neighbour reported a dinner table argument with his wife. Many came from the County and similar jails at the end of their sentence, being held pending deportation.

|

| Part of the ‘day room’ area. One Mexican we spoke to was funny, saying he couldn’t understand why we were there. “People like you built this country” he said. |

O. J. Simpson’s legacy

There were many woeful tales of families being torn apart after hysterical wives or over-eager neighbours had called the police. Since the O. J. Simpson affair, an arrest had to be made whenever the police were called to a domestic dispute. In California “domestic violence” now includes a shouting match; smacking a child is “child abuse” and can attract a charge of “assault with a deadly weapon” (your hand); people are prosecuted for DUI if they only have car keys in their pocket. Americans, perhaps especially Californians, are not ones to do things by halves.

Consequently minor misdemeanours, and not so minor crimes, had huge, knock-on effects. Families were torn between continents and people were being returned to countries they barely remembered, if at all. Such are the blessings of mass mobility and the changes since 9/11. Ultimately mass immigration is not good for anyone, as will become increasingly plain as population levels inexorably rise and resources diminish.

The worst part of our incarceration was being shipped out to attend court hearings. We’d be knocked up at 4am or thereabouts, processed, changed into our own clothes, which were thoroughly grimy from previous occasions, then chained in groups of four or more with handcuffs and ankle bracelets. After the drive, long hours would follow sitting around in the tanks beneath a skyscraper in central Los Angeles, all for a hearing or interview lasting five minutes or so. American bureaucracy is very inefficient. Sometimes we didn’t get back to our cells, or different ones, until 2am the following morning. It took several days to recover from such an outing, or even longer if a cold had been contracted along the way.

One time we were sitting in the ground floor reception area after a trip to the immigration court, watching the inevitable American football on the inset TV’s, and the local police had brought a white meth-user to the jail. He had thrown some food around his holding cell and was shouting. We were herded into another cell, the guards gathered and we heard him painfully being tasered. When we emerged he could be seen through the reinforced glass windows strapped head to toe in a special chair. Just as troubling however, was the demeanour of the jail staff. The exuberant attitude of the guards, predominantly female, after having wielded physical power against an inmate was almost palpable. Even the most minor disturbance on a module provoked an immediate lockdown and the arrival of a “crash team” of guards.

Inmates’ stories

Many came to our facility from the County Jail, and they said Santa Ana Jail was like Disneyland by comparison. One English football trainer who had been working without a green card and sent to the County Jail for a DUI told us how his fellow inmates had rioted. They’d been in another tank, a single large room containing 40-100 prisoners which is a common feature of American jails, for several months without a sweeping brush or any cleaning materials. Eventually some were provided, but they had hardly begun clearing the accumulated debris from the gutters in the concrete floor when the guards demanded the mops and brushes back. A riot ensued, with the prisoners eventually being herded onto the roof, out of range of the cameras, and soundly beaten. He had been travelling between Britain and America for years, and reported that almost all of his property in America had been confiscated on the grounds that he had not been legally in the country when he earned it.

This was nothing, however, to Mexican prisons in which often the tank consists of a dingy room with a few infested mattresses and a hole in the floor in the corner for a toilet. There was a story in the newspaper of a 17-year-old Mexican girl caught shoplifting who’d been put by the warders into a tank of men. She’d spent over forty days amongst the men, having to grant sexual favours to them in order to eat. The most surprising thing though, was that the Spanish-language newspaper interviewed people in the street about it and some said the girl had deserved it!

Another fantastic event which occurred while we were at Santa Ana was two American judges being convicted of corruption. For years they’d been sending juveniles to jail for silly first offences and receiving kickbacks from the company which ran the facility. That was in the newspaper, and has subsequently been detailed in a Michael Moore film, but there were many tales of prisoners being moved to another jail on their day of release, or one or two prisoners being specially flown from Arizona accompanied by a dozen guards, simply to collect the tariffs a jail is able to charge for such movements.

We learned that the Lancaster facility had a much harsher regime, with inmates being roused at 5am each morning for roll-call. Prisoners were housed in large barracks with rows of double bunks and allowed to walk outside during the day. The Marshals there sold cigarettes to inmates at $10 or $15 each. Its best feature was that the immigration court was actually located on the grounds, and hearings took place at twice the frequency of the LA immigration court, halving the period of detention.

|

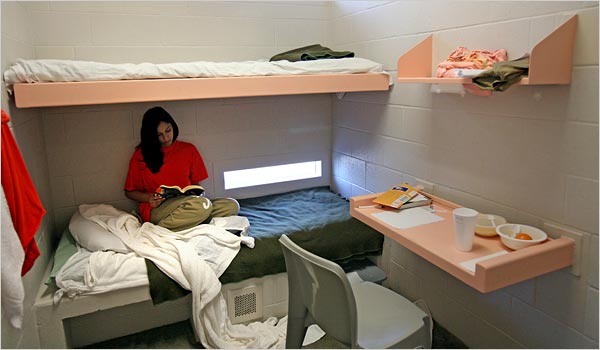

| What the cells were like, though this is a cell in the female module opposite ours. One power-mad guard used to delight in making everyone surrender the extra blankets we had acquired to make life a little more comfortable. |

Legal minefield

It took nine months for our asylum applications to run their course, during which time our attorney ran wild and wasted the $10,000 our supporters had paid into our legal fund. I think what happened was that he needed money, perhaps to pay for his several mortgages, and consumed our funds preparing a massive submission to the court which would have been just as likely to be rejected had it been condensed into two pages. In the ensuing recriminations he showed signs of mental instability and threatened to turn up at court and make a scene.

Thus I can understand how American lawyers have such a bad reputation. Even if you’re fortunate enough to be acquitted by the American legal system, you’re often left bankrupt by it. Their equivalent of Legal Aid is the Public Defender system, and you’re lucky if they spend fifteen minutes on your case. Such is the volume of cases that a large majority are dealt with by plea bargains, signed under duress and with terms which are often later regretted. Traditionally, Americans have a strong Puritan streak which may account for a certain meanness towards anyone who transgresses the law, apparently with little or no appreciation of mitigating circumstances.

If recent trends were to continue there could come a point, with the huge sentences often dished out in America, and indeterminate sentences here, at which society simply ceases to be viable. Such a large proportion of the working population would either be in jail or employed keeping them there, or employed in associated roles such as security guards and lawyers, that no one will be left to actually create any wealth.

The “prosecutor,” i.e. the lawyer acting for the government in our court appearances, was a woman of about 35 who piled on the pain so much she might have been on a mission. Other people we knew well by this time would appear at court hoping for a win, or at least to be granted bail, only to have yet another objection dredged up, which would then have to be dealt with two or three months hence. The proceedings dragged on interminably. The majority of cases were more straightforward however, and applicants were often sworn in five at a time and summarily ordered deported. Many privately boasted that they would be back in LA a few days after their deportation.

The only time a departure from judicial impassivity appeared was when the judge, also female, seemed to seek our approval for this judge-prosecutor duo’s decision, some years previously, to grant political asylum to an IRA murderer of two policemen. Our response was noncommittal, but in any event it became clear that our fate had been sealed from the outset. When our final hearings took place, the prosecutor’s case was flimsy in the extreme, consisting of quoting EU documents announcing Brussels’ intention (not existing law) of criminalising the expression of certain opinions on the internet. Still, judgement was not forthcoming and only arrived in written form two weeks later, and had obviously been crafted to make an appeal as difficult as possible.

Political gimmick

Flight from Britain to claim political asylum in America was a failure, and added four months to our sentence on our return, but as a political gimmick it was a success. The system showed its true colours, demonstrating that Western governments consciously act against the interests of their own people. Not only was our situation broadcast over many internet sites, we got nearly a full page in the prestigious LA Times. I’ve done my share of freelance journalism, and know that journalists almost invariably adhere to a predetermined script when they write their stories. In any reporting of nationalist politics the script words are trotted out: “Nazi,” “racist,” “violent demonstration” (even if wholly attributable to the opposition), “far-right,” “six million” etcetera and ad nauseam. By contrast, the LA Times story called on the American tradition of free speech, which a large consensus supports, regardless of what is said. It was the best publicity we had had, while the Yorkshire Post coverage was so biased it was actually dishonest.

Nationalists are generally ignored by the media, unless and until they are being dragged off to prison. A telling example occurred with the first book I published, Forged War Crimes Malign the German Nation by Udo Walendy (the book was imported, assigned an ISBN and formally published under the Heretical imprint). The book, containing over 80 photographs, detailed how scores of Holocaust and other WWII atrocity photographs had been forged. A common method employed teams of artists, under orders from Stalin, drawing large, wall-sized pictures which were then photographed and included in books published in Soviet satellite countries such as Poland. Walendy meticulously analysed the “photographs” for light sources, perspective and other inconsistencies and, once pointed out, their falsity is usually glaringly obvious.

The Hull Daily Mail approached me wanting a story, but it quickly became clear that I was the intended focus, not the book. I showed it to them, and the excuse was given that the photographs, even if fake, were not suitable for family viewing. Then I suggested that they feature the “photos” of mountains of shoes, in which the shoes had fallen in an identical pattern at several different locations. That a book was being published, and by a local publisher, showing that our libraries had been seeded with fake photographs was certainly newsworthy, but no story ever appeared.

|

| The other end of a module. In the two we spent time in, the cell doors stayed locked most of the time. A large proportion of our 11 months was spent reading. New books that came in were eagerly passed between inmates. |

Back to Blighty

There is no doubt that we could still be in Santa Ana City Jail today. Although most inmates in the module arrived and were deported within a few weeks, we were part of a hard core of a dozen or so borderline cases or applicants for political asylum which, with various appeals, process could be dragged on for years. Some clearly preferred the jail to returning to their home country because, frankly, life incarcerated in some Western countries is preferable to freedom in many third world ones. My advice to others was “Go back and get on with your life” and the time came to follow that advice. Ultimately perhaps only one or two percent successfully challenged their deportation orders.

Another two months were spent waiting, probably because previous rapid deportations had been challenged and had led to large settlements. My lasting impression of American officialdom was of a system paralyzed by political correctness and ponderous in its procedures either because someone had previously sued, or they were conscious of the ever-present possibility they would be.

At last we were flown back to Britain accompanied by four federal flunkies who handed us over to police at Heathrow Airport. The worst of it is that the eleven months we spent in jail in America weren’t taken off our sentence, it being out of the jurisdiction. Back in Britain, it was a relief not to be marched around, army-style, whenever we left the module and strip-searched even after an attorney visit. Most appreciated though was to be reunited with officers and inmates alike who share our national sense of humour. I’d rather be in a British jail any day.

Simon Sheppard