|

||

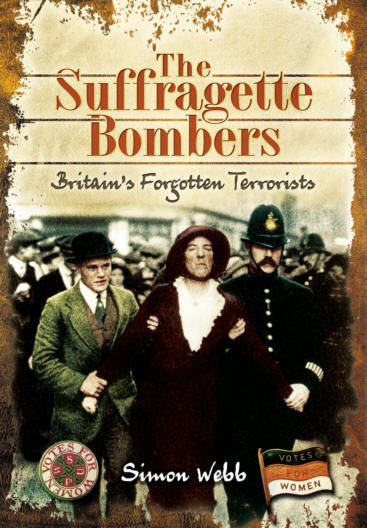

Excerpts fromThe Suffragette BombersBritain’s Forgotten TerroristsSimon WebbPen & Sword Books, Barnsley, 2014 |

The Public Mood, 1914

At about the same time that the bomb was planted at Dudhope Castle, an explosion was heard in the village of Breadsall in Derbyshire. Shortly afterwards, the very old Church of All Saints was seen to be on fire. The fire brigade was summoned from Derby and the villagers did what they could, but the church was entirely gutted by the fire and by morning, the church had burned to the ground. No suffragette leaflets were found after the attack, but a hairpin was discovered near a small window, where it was thought the church might have been broken into. As previously noted, the finding of hairpins in this way was often a hallmark of suffragette attacks. There was a curious sequel to the attack on the church in Breadsall. Two years later a former suffragette was convicted of plotting to murder Lloyd George and evidence was given that she had also boasted of destroying the church.

All Saints in Breadsall was the second church to be wholly destroyed by fire in the early hours of 1 June 1914. At 3.00am a fire began which left only the walls standing of the parish church at Wargrave, near Reading in Berkshire. The roof caved in and the bells fell from the tower. No glass was left in any of the windows and all the interior fittings were reduced to ashes. Postcards bearing suffragette messages, such as, ‘To the Government Hirelings and women torturers’ were found in the churchyard.

Financially, the WSPU had never been in better shape that summer. The group’s income in the year up to February 1914 was the highest it had ever been. The increasingly strange targets of the arsonists and bombers had done nothing to discourage the wealthy backers, who were prepared to donate thousands of pounds to the suffragette cause. Asquith and his Home Secretary, Reginald McKenna, were both well aware that the key to suppressing the WSPU and ending their terrorism lay in hitting at those who were encouraging the suffragettes by handing over large sums of money. A plan was accordingly formulated to take action against these shadowy individuals.

At 5.30pm on 11 June, the Home Secretary rose in the House of Commons to outline the government’s new strategy for dealing with the suffragette attacks. He began by explaining that although the number of incidents overall was declining, those that did take place were increasingly serious. McKenna talked of the ‘sinister figures with money bags’ who selected dupes and paid them a pound or two a week to carry out attacks and go on hunger strikes. The authorities now had enough evidence to bring a test case of civil action for damage to property and also criminal prosecutions for inciting violence.

There now occurred one of those strange coincidences that would not be out of place in a play or film. The Home Secretary was speaking in calm, measured tones about the sensible policies of the Asquith administration and how these were sure to triumph in the long run. He explained that the government was taking, ‘patient and determined action’. No sooner were the words out of his mouth than there came the sound of an explosion. Another bomb had gone off, this time near to the Houses of Parliament. A number of MPs jumped to their feet and hurried from the chamber to investigate.

In nearby Westminster Abbey, tourists were heading towards the exits, the abbey was due to close at 6.00pm and it was now a quarter to. There had been what witnesses described as ‘a terrific explosion’ and then a column of smoke and dust rose from the chapel where the coronation chair was kept and slowly spread through the rest of the abbey. The chair, on which monarchs have sat during their coronations since 1300, was slightly damaged by the bomb, which was powerful enough to have chipped the stonework of the ceiling high overhead. The explosion was heard a long way down Victoria Street and even, as we have seen, in the Houses of Parliament.

The police sealed off Westminster Abbey after the bomb attack and arrested two women. They proved to be harmless Danish tourists and were soon released. Apart from some superficial marks on the walls and ceiling of the chapel in which the coronation chair was kept and a few bits of broken stone carving, there did not appear to be any serious consequences in the aftermath of the explosion. This was regarded as being extremely fortunate because the bomb had been packed with pieces of iron, obviously with the intention of causing as much damage as possible.

It was to be almost 40 years before the discovery was made that a another very ancient relic had been irreparably harmed by suffragettes. At Christmas, 1950, four Scots nationalists ‘kidnapped’ the Stone of Scone, which had been kept beneath the coronation chair for over 600 years and which had originally been brought to London after being captured from the Scots. The four students, who had hidden themselves in the abbey overnight, pulled the sandstone block from under the coronation chair where it rested. To their amazement, they found that it had been broken in half at some time in the past. It is likely that this was a result of the bomb which exploded nearby, almost 40 years earlier.

Apart from the obvious motive of wishing to prevent terrorist activity in the United Kingdom, the Prime Minister and Home Secretary had other good reasons for wishing to put an end to the arson and bombings being carried out by members of the WSPU. One fear was that if the terrorism continued, then members of the public would take matters into their own hands and undertake revenge attacks on the suffragettes. This was not a far-fetched idea and raised the spectre of lynch mobs on the streets of Britain. Events that took place in the days following the bombing of Westminster Abbey showed all too clearly that this was a genuine threat to public order.

On the same day that the bomb was planted in Westminster Abbey, there were two other suffragette attacks, both in Surrey. Reigate cricket pavilion was burned down and a determined attempt was made to set fire to an ancient church in the town of Chipstead. Three separate fires were started, by piling oil-soaked material against the wooden doors of the church. Fortunately, the rector, aided by local residents, managed to put out the fires before they caused much damage, but news of these other attacks did nothing to calm the hostility that many members of the public were now feeling towards the suffragettes. This hostility had nothing whatever to do with the principle of extending the franchise to women. It was simply anger at those responsible for conducting a campaign of random attacks which, if they continued, would inevitably end up in causing more pointless injury or death to innocent bystanders.

The government was right to fear public disorder if something was not done to put an end to the terrorist attacks. The mood of the country was running very strongly against the suffragettes and, by association, the very idea of women’s suffrage was also becoming unpopular. The Sunday before the Westminster Abbey bomb, a number of public meetings were broken up by hostile crowds. At Hyde Park, the police had to rescue a speaker from the WSPU, when a very large and angry crowd assaulted her. At Hampstead, a mob seized two women and began dragging them towards a pond, with the intention of ducking them. Again, the police were forced to intervene. There was similar trouble at Clapham Common, when at a public, open air meeting one of the speakers made reference to bombs. She too, narrowly escaped violence. The situation became even more hazardous for the WSPU after the attack in the Abbey.

The day after the attacks in London and Surrey, some members of the WSPU tried to set up a stand at an agricultural show in Portsmouth. The reaction of those visiting the show was so violently antagonistic towards the sight of suffragette banners that a near-riot ensued, with the women being pelted with bottles and bricks. The police had to rescue the suffragettes and escort them to safety. A day later, there was a similar incident at nearby Southsea.

In London, suffragettes began distributing leaflets at a music hall in the East End and were roughly manhandled and ejected from the theatre. It was noticed that the women in the audience were displaying more dislike of the activists than the men. Two days later, suffragettes attempted to disrupt a service in Westminster Abbey, by standing up and shouting slogans. This was more than a little tactless considering that the Abbey was the very site of one of the latest outrages. The women were chased from the abbey and once again, the police were forced to protect them from the wrath of ordinary men and women who had had enough of terrorism.

On the evening of Saturday, 13 June [1914], just two days after the explosion in Westminster Abbey, there was an attempt to hold a WSPU meeting on open ground at Palmers Green, a district of north London. One of those who helped to organise the meeting was Herbert Goulden, Emmeline Pankhurst’s brother. A crowd gathered, not to hear the speeches of the suffragettes but rather to put an end to the event. Goulden was knocked to the ground and several women were assaulted. Eggs and flour were thrown at those taking part in the meeting. Even when, with the help of the police, Herbert Goulden was put onto a tram, the crowd followed and laid siege to his home. It was a riot in all but name. That same weekend, there were similar disturbances in Leicester and on Hampstead Heath, where a platform set up by members of the WSPU was broken up by the crowd and thrown in a pond. (pp. 146-149)