|

||

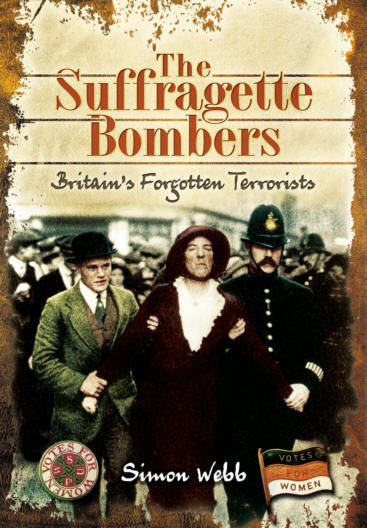

Excerpts fromThe Suffragette BombersBritain’s Forgotten TerroristsSimon WebbPen & Sword Books, Barnsley, 2014 |

Terrorism by Champagne Suffragettes, 1914

The fiction is maintained, whenever suffragette violence is mentioned, that great care was taken by those initiating attacks to ensure that nobody was hurt in the process. Two bombings carried out in January 1914 should alone be sufficient to give the lie to this assertion.

At 8.00pm on Wednesday, 7 January 1914, in the city of Leeds, an explosion took place which was so loud that it was heard across the entire city. It had taken place at the Harewood Territorial Army Barracks in Woodhouse Lane, one of the main streets of the city. The barracks were being used as a temporary police base at the time of this incident. It was a miracle that nobody was seriously hurt by the dynamite bomb which was lobbed over the wall of the barracks, landing near the canteen. A caretaker was cut by flying glass when all the windows in the nearby buildings were blown in. A near casualty was Sergeant-Major Payne of the West Riding Ambulance Corps. He was sitting in his office and the blast knocked him off his chair.

The attack on the barracks was the second bomb to explode in Leeds in the space of 24 hours. The night before, an electricity generating station in the Crown Point district of the city was damaged by high explosives. Although no responsibility for these two attacks was claimed by the WSPU, it is hard to know who else could have been to blame. The suffragettes were the only terrorist group operating in Britain at that time.

In 1873, an enormous glasshouse was opened at the Glasgow Botanic Gardens. It was a fantastic structure, with a 150-foot-wide dome, made up of small panes of glass. This was called the Kibble Palace, after the man responsible for its construction and soon became a landmark in the city. Both Benjamin Disraeli and William Gladstone were, at different times, installed as rectors of Glasgow University, both events taking place in the Kibble Palace.

In the early hours of 24 January 1914, the watchman employed to keep an eye on the Kibble Palace at night and protect it from thieves or vandals, was making his rounds of the building. He checked that nobody was in the Botanic Gardens after dark and that nothing was amiss. His work entailed nothing more arduous than chasing the occasional adventurous teenager out of the gardens. This night though, was due to be different. As he patrolled the outside of the glass palace, he spotted something very odd. It was a sputtering length of string. When he bent down to investigate, he found to his horror that this was a fuse, attached to a bomb. Instead of fleeing in panic, the man took out a penknife and calmly severed the fuse, thus rendering the bomb harmless.

As the night-watchman stood up, he must have been congratulating himself on a narrow escape. At that moment, a second bomb exploded nearby, with devastating force, shattering the sides and roof of the great glasshouse. It was the closest of shaves for the man, who fortunately had his back to the explosion, which showered him with fragments of broken glass. Investigation of the scene in daylight provided a chilling insight into the minds of those responsible for the attack on the Kibble Palace. A woman’s veil was found, together with an empty champagne bottle and the remains of some cakes. Footprints indicated the presence of at least two women.

Whoever had planted the bombs had sat, eating and drinking, waiting for the best opportunity to strike. They must have seen the watchman on his rounds, knowing perfectly well that somebody was walking around the glasshouse. Setting off two explosions under such circumstances shows that those who lit the fuses did not care at all if this man was injured or even killed by their actions. Later that year, Marion Crawford, a prominent member of the WSPU, was sent to prison for two years for this attack, she was lucky not to have faced a charge of murder.

Less than a fortnight after the bomb attack in Glasgow, three country houses were attacked in Perthshire, two burned to the ground and the third severely damaged, but not wholly destroyed by the fires which were started. Once again, the suffragettes showed a complete disregard for the lives of others.

The owner of Aberuchill Castle was not in residence at the time, but a number of domestic staff was living on the premises, in quarters at the top of the house. By great good fortune, the alarm was raised and they were able to escape, but the scenario could have turned out very differently. In modern histories of the suffragettes, this kind of activity is almost invariably dismissed casually as an attack on an ‘empty house.’

The terrorist attacks of the suffragettes were becoming more and more erratic and irrational. Why anybody would imagine for a moment that blowing up a greenhouse would lead to the extension of the franchise is something of a mystery. Even by the standards of the WSPU though, the next attacks in February 1914 were baffling.

In 1906, a Carnegie public lending library was opened in Northfield, a suburb of Birmingham. It was hugely popular with local people. At 2.00am on 12 February 1914, the library was broken into and a fire started. Within a few hours, the building was gutted: the roof had fallen in and the library was a smoking ruin. When dawn came, a piece of paper was found attached to the railings at the back of the building. It proclaimed, ‘Give Women the Vote.’ Nearby was a parcel, which when opened proved to contain a copy of a book by Emmeline Pankhurst. Inscribed in this was the message: ‘To start your new library.’ Much anger was generated locally against the suffragettes by this singularly pointless act of vandalism.

On the same night that the library at Northfield was burned to the ground, a bomb was planted at the home of Arthur Chamberlain. Moor Green Hall was a mansion near Birmingham and somebody had broken in and left a bomb, which was supposed to be triggered by a burning candle. Fortunately, this primitive timing mechanism failed to set off the explosives.

The church of St Mary’s in the tiny Scottish village of Whitekirk, is one of the most ancient in Scotland. Dating from the 1100s, it was in medieval times a site of pilgrimage. It seems inconceivable that anyone could wish to damage such a place, but a little over a week after the library at Northfield had been destroyed, a suffragette squad arrived at St Mary’s Church in the middle of the night and burned it down. A photograph taken the day after the fire shows the church a smouldering wreck, with the roof having fallen in and all the windows blown out by the heat. We can only imagine what the residents of the village felt about the loss of their beautiful old church and the feelings aroused against those who had carried out such a vindictive act.

On the first day of spring, the terrorists turned their attention once more to London. In 1914, the rector of the Church of St John the Evangelist, Westminster was the Venerable Albert Wilberforce, Archdeacon of Westminster and Chaplain to the House of Commons. Perhaps it was his connection with parliament that led to his church being targeted by the suffragettes. If so, then the terrorists were making a grave mistake as the Venerable Wilberforce was an outspoken supporter of women’s suffrage. Half an hour after the end of the evening service at St John’s, on Sunday, 1 March, a bomb exploded in the gallery. Stained glass windows were blown out and a number of pews were destroyed. This was the first of a number of bombs aimed at churches in central London.

By the beginning of spring 1914, the WSPU had been reduced to the status of a very small militant group, rampaging around the United Kingdom and attacking increasingly peculiar targets, such as greenhouses, libraries and churches. The idea of ‘social purity,’ which was becoming an obsession with both Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, could only have the effect of alienating still more potential supporters of the WSPU. The only thing that the group really had going for it was the input of wealthy donors who were paying the wages of the terrorists and so enabling them to continue their activities. The WSPU would struggle on for another six months, but it was really dead on its feet, disliked by many of the general public, viewed with detestation by the main political parties and regarded as a positive nuisance by the moderate suffragists who were making great strides by working patiently with sympathetic members of the Liberal and Labour parties.

The one thing that the WSPU did have though was money. The spectacular attacks, which attracted so much attention, also prompted various rich women to send more money to Mrs Pankhurst. Overall membership numbers might be dwindling but those who remained in the organisation were still ready and willing to conduct further terrorist attacks. The fact that their activities were now acknowledged even by other suffragists as harming the cause, made not the slightest difference. The bombings and arson continued. (pp. 136-139)